Resident Theologian

About the Blog

My latest: on Houellebecq (in Mere O) and Forgiveness (in Comment)

Links to two new essays just published online.

Two new essays for y’all.

The first was published last week at Mere Orthodoxy, on January 7, the ten-year anniversary of the publication of Michel Houellebecq’s novel Submission, which came out the same day as the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris. Jake Meador was kind enough to get it up in time for the anniversary—I was surprised not to see any other outlets noting the date—and gave it the title, “A Future Worthy of Life: Houellebecq, Decadence, and Sacraments.” It’s about the insights and shortcomings of Houellebecq’s critique of the West, parallels in other recent novels, and the superior vision (and prescription) found in P. D. James’s Children of Men. (The lesson, as always: James is the queen.)

The other essay came out last month in the print issue of Comment, but it’s been behind a paywall until today. In the magazine it has the title “Promise, Gift, Command”; online it goes by “The Theological Terrain of Forgiveness,” which tracks with the issue’s overarching theme of forgiveness. It’s my attempt at locating, delimiting, and unpacking the Christian doctrine of God’s forgiveness of our sins in Christ, by the Spirit, through the sacraments—and the implications for our own call to imitate this divine action in our daily lives.

Thanks for reading. More soon.

Penance and punishment for the canceled

Thinking aloud about the range of social penalties—whether understood as punishment or penance—available to be applied to public figures guilty of wrongdoing.

Think for a moment about public figures who have been “canceled.” I don’t mean instances of reckless or unjust “cancelling.” I mean men and women who are guilty of the accusations, who caused scandal by their foolish or harmful or wicked actions, and who received some combination of social, professional, financial, and legal consequences as a result of their actions. I’m thinking of pastors, professors, actors, artists, musicians, comedians, and politicians. They are guilty, they know it, they admit it, and they suffer for it.

Here’s the question. What is the appropriate punishment for such people? What severity should characterize it, for how long, and why?

The public conversation on this topic is fuzzy at best. Critics and pundits quickly resort to the passive voice, to mention of how “some people feel,” to the “challenge” and “struggle” and “questions with no answers,” always with the kicker that the author finds him- or herself made “uncomfortable” by the whole subject. This amounts to one long dodge. No one, at least no one that I can find, is willing to say what would actually qualify as appropriate penalties or penance for a guilty person; or, alternatively, that no penalty or penance is possible in this or that case.

I don’t imagine that society as a whole could reach anything like consensus on this question. But for those of us who think and write about it, we could at least find some shared analytical ground on which to discuss it. To be sure, the punishment has to fit the crime, which means that every case is different. Nevertheless, for all cases, there is a range of possible penalties and modes of penance available to both official authorities and the populace in general. Assuming none of us wants the guilty canceled publicly tortured (a punishment many societies have employed!), I came up with twenty possible consequences for a public figure caught having done something wrong. They range from least to most severe, more or less; they distinguish temporary lengths of time from permanent consequences; they are not all mutually exclusive. Here’s the list:

A formal apology

Time away from the Eucharist

Time away from the spotlight

Time away from one’s job, post, or profession

Time away from a position of leadership

Time away from one’s family

Time away in a medical, therapeutic, or monastic institution

Being fired

Being blacklisted

Permanent formal banishment from one’s profession

Permanent formal banishment from any type of public role

Permanent public social shame

Permanent financial destitution

Permanent legal separation from one’s spouse and/or children

Permanent sentence to a medical, therapeutic, or monastic institution

Exile from one’s homeland

Prison for a time

Prison for life

Capital punishment

Suicide

Here’s why I think this list is useful.

First, it names aloud the range of possible punishments a society might inflict on a person guilty of some social wrong (not always a crime, legally speaking; usually a sin, theologically speaking). This list addresses society and each of its individual accusers: Which do you want for the guilty? Which is just? Which is not?

Second, the list clarifies that penance and punishment come in a variety of forms. Sometimes it’s mild; sometimes it’s extreme. Sometimes it’s tacit; sometimes it’s official. Sometimes it’s temporary; sometimes it’s permanent. Again: Which should apply in such-and-such case? What reasons or criteria are at work?

Third, the list shows the stakes involved. Options 6-20 are all personally devastating, even if some of them are temporary. No one wants to suffer them. In truth, no one wants 1-5 either. They’re all awful in one way or another. So we shouldn’t minimize the suffering involved. In particular, folks who reject the concept of retributive justice should be careful about which, if any, of these penalties they endorse—for any kind of wrongdoing—and why.

Fourth, the list contains an ambivalence. Namely, are these penalties to be inflicted on the guilty because they deserve it? Or are they forms of public penance by which and through which the guilty are absolved, socially or legally, of the guilt and debt they have contracted by their wrong? In other words, if a guilty man consents dutifully to whichever of these punishments his institution or society deems just, is he thereby relieved of his social burden? May he thereupon reenter whatever form of professional, political, public, or ecclesial life he formerly led—with a clear conscience and a reasonable expectation of being treated like anybody else? Or is the scarlet letter an indelible branding? Is the scorn and shame justly cast on a guilty woman hers, by rights, forever? “Till death do us part”?

This last question is not quite the same one pundits and critics like to ask. They tend to ask, “How much time away is enough?” And they invariably report—without exception, in my reading—that the time away is never enough. Yet they cannot specify how much longer would have made it sufficient. Their discomfort endures.

The problem here is not that some of us sometimes sense that a person should stay away indefinitely. It would be perfectly just, in some cases, to apply penalties 8-12 above. Being an actor or a comedian or a senator or a priest is not a right; it’s a privilege. I’m more than willing to believe that there are actions that permanently, not temporarily, disbar one from any of these or other public professions.

No, the issue is not whether some people do “return to the limelight too fast.” Plainly some do. The issue is whether we possess collectively a concept, not to mention a coherent practice, of public penance, whereby we would say in certain cases that a guilty person paid his dues or suffered long enough or needn’t hide in the shadows forever. That criminality and sin need not, in some cases at least, render a person unclean for life. That the guilty can reemerge from their shame, without fear of further or constant shame—even and especially when that shame was valid and deserved, not coerced or false or merely imposed from without.

As many have noted, we need an account of public and social forgiveness. But in whatever discursive context we find ourselves in—social, moral, legal, civil, religious—forgiveness follows contrition and justice both, and the price of justice is often steep. What should the guilty pay? What do they owe? Will we receive them anew once the ledger is clean? Those are the questions we need to be asking. Speaking clearly about penalties, punishments, and penance is one step toward answering them.

Les Murray on love and forgiveness

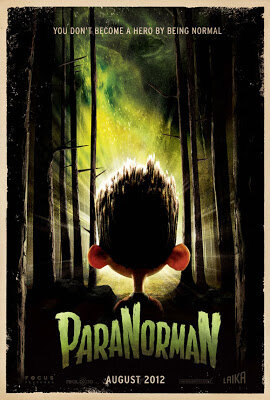

"Nobody's stronger than forgiveness": breaking the cycle of fear and violence in ParaNorman

Did This Ever Happen to You

A marble-colored cloud

engulfed the sun and stalled,

a skinny squirrel limped toward me

as I crossed the empty park

and froze, the last

or next to last

fall leaf fell but before it touched

the earth, with shocking clarity

I heard my mother’s voice

pronounce my name. And in an instant I passed

beyond sorrow and terror, and was carried up

into the imageless

bright darkness

I came from

and am. Nobody’s

stronger than forgiveness.

—Franz Wright, God's Silence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), p. 22

- - - - - - -

(Spoilers to follow.)

(Spoilers to follow.)Written by Chris Butler and co-directed by Butler with Sam Fell, ParaNorman seems at the outset to be a rather straightforward "kids' movie" within a certain recognizable genre. It quickly becomes evident, however, that the story being told is not as ordinary as one might expect.

Norman Babcock is an outcast at home and at school, and for a simple reason: he sees the ghosts of dead people, regularly talks to them, and doesn't hide the fact. His dad thinks he's a weirdo, his mom isn't sure how to relate to him, and his sister can't stand him. At school people part the way for him and whisper as he trudges along; he keeps a wet rag in his locker to wipe off the word "FREAK" scrawled anew each day on his locker door. A bully, Alvin -- a cinematic Moe from Calvin and Hobbes if there ever was one -- makes his life miserable. The one gleam of light in this daily darkness is the friendly overtures of Neil, a similarly bullied "fat kid" who doesn't let it get him down. When Norman says he prefers to be alone, Neil agrees: He just wants to be "alone together."

Norman lives in Blithe Hollow, a town founded by Puritans and known for its trial and execution of a purported witch nearly 300 years ago -- in fact, tonight is the eve of that anniversary. The legend is that at her sentencing, the witch (imagined as an ugly old green-nosed hag) cursed her accusers, and that all seven of them (the judge and the jury) went to their graves bearing this curse.

A kooky uncle who can also see and speak to ghosts finds Norman and (just before dying himself) tells Norman it's up to him to keep the curse at bay, that very evening before midnight. Unfortunately, before he can figure out quite how to follow his uncle's instructions, the seven Puritan accusers rise from the dead as zombies and start pursuing Norman (albeit very slowly) and whoever is with him. As Norman tries to escape and figure out how to kill or at least send them back to the grave, he picks up a ragtag crew: Alvin, Neil, his looks-obsessed sister Courtney, and Neil's beefy but dim-witted brother Mitch. Unsurprisingly, once the town discovers the dead walk the streets, they form a mob (armed with pitchforks, shotguns, and bowling balls) and chase both Norman's crew and the zombies to city hall, where in a frenzy they seek to kill not only the zombies but Norman himself, too, for bringing this terror upon them.

An unexpected series of events, however, reveals the true nature of what is going on. The undead Puritans don't want to kill Norman or anyone else: they want their curse undone. They want peace in death, not more death for others. Norman sees the reality of what happened three centuries before: the person sentenced by the court to death for witchcraft wasn't a green-nosed hag, but a child like him -- a little girl who happened to be playing with fire (both literally and figuratively), and found out by the wrong people. Caught and punished unjustly by these townspeople so blindly fearful of her, she in her anger and fear of them in turn cursed them to their graves, so that they would never know the peace she herself was robbed of.

Now Norman sees, as do his sister and and oddball friends: The curse isn't limited to the Puritans, nor are its consequences merely to be trapped in a living death. No, the curse is on the entire town, for the very cycle of fear of the unknown and the turn to violence has engulfed the mob standing outside city hall, trying to burn the place down. And it won't end with the death of either the zombies or Norman himself. Something else, something new, has to happen.

So Norman leads his crew and the zombies outside to meet the mob where they stand. After stilling their frenzy, he tells them the story he just learned. Following Norman's lead, his unlikely fellows -- a resentful sister, an overweight outcast, a former bully, and a (later revealed as gay!) beefcake -- bear witness to the crowd that what Norman has told them is true, and further appeal to them to let go of their fear. For in fact, they have nothing to fear; the zombies don't want to hurt them, they only want to find the means to pass on peacefully.

As the truth dawns on the mob, the camera pans across their feet, as each and all drop their weapons: a club, a pitchfork, a shotgun, a bowling ball. "At this, those who heard began to go away one at a time, the older ones first . . ." The town lays down their instruments of violence, with eyes opened by the truth, freed from their bondage to fear of the other as threat.

But this isn't the end. The ghost of the witch, now enraged, begins to wreak havoc on the town. So Norman's parents take him, his sister, and the zombie Puritan judge to the witch's unmarked grave. There Norman engages in a climactic encounter with the witch's ghost, not with force or deception, but just as before with the crowd: with a true story. In fact, the way in which previous "ghost-seers" like him had kept the witch at bay was by reading a fairy tale to her, that is, they read her a nice bedtime story to palliate her righteous anger and get her to "sleep" for a little while longer.

But Norman knows better. That only puts a bandage on the wound, it won't heal the town's history or the witch's hurt. So he tells her a different story: her own. Though she tries to stop him in every way she can (with fantastic and terrifying powers), he re-narrates her life, without blushing or overlooking the hurt and the wrong and the injustice of it. But finally -- with what feels like his last ounce of energy -- finally he helps her to see. And she sees not only her tragic situation, but also the tragic nature of her accusers: they weren't pure evil or all powerful; they were afraid of her, hard as it is to believe. And though what they did was unspeakably wrong, to inflect on them and thus on the town what they inflicted on her is only to become a monster like them, when she could choose otherwise and free the town of its curse.

Reverting for a moment to her living form, Aggie -- for that was her name -- tells Norman of her sadness, how she misses her mom, how she was only playing with fire. Norman comforts her, but urges her to let go and be at peace, and to do so she has to forgive. Aggie asks Norman: What is the ending to the story he's telling? Norman replies that that's up to her.

After considering, the witch opts for peace; Aggie forgives those who knew not what they did, and so gives up her spirit, passing on peacefully to be with her beloved mother. The zombies, too, pass on, but not before changing from undead to dead, that is, from zombies to ghosts: they go on as themselves, the curse undone, rather than into one more mode of accursed existence.

Norman walks through the rubble of the town, listening to his neighbors' conversations. A former outcast, he surveys those once divided from him and from one another now chatting and listening and laughing with one another. Returning home, he plops in front of the TV for his usual routine of horror flicks. Typically alone with his movies and the ghost of his grandmother, his family joins him, Norman's dad even going out of his way to acknowledge the previously doubted presence of his deceased mother.

Whether in his town, with his new friends, or here at home with his family, Norman isn't alone anymore. The dividing walls have come down; the cycles of fear and violence have been broken; the weirdos and the bullies have embraced; the town knows its history, broken and redeemed. No, neither Norman nor his town nor his family is alone; no longer are they isolated from one another.

In Neil's words, they're alone together.