Resident Theologian

About the Blog

Carr, Sacasas, and eloquent reality

A long reflection on an essay by Nicholas Carr engaging L. M. Sacasas about enchantment, reality, and contemplation.

In a list of the best living writers on technology in the English language, the top ten would include Nicholas Carr and L. M. Sacasas. Yesterday the two came together in an essay I can’t get out of my head.

The essay in question is the third in a series called “Seeing Things” on Carr’s Substack “New Cartographies.” Titled “Contemplation as Rebellion,” it continues Carr’s reflections on the nature of perception in a digital age. Perception is both neurological and social; it is a mediated phenomenon; it can be done well or poorly, deeply or cheaply. And works of art, especially visual art like paintings and engravings, have the power to call forth the kind of attention that repays time, energy, focus, and affection.

Interwoven with these reflections is Carr’s intervention in the “enchantment” discourse, one I have myself dipped into more than a few times (especially in conversation with Alan Jacobs). In yesterday’s essay, following meditations on Heaney and Hawthorne, Carr turns to something Sacasas wrote last August titled “If Your World Is Not Enchanted, You're Not Paying Attention.” He begins with an excerpt from Sacasas:

This form of attention and the knowledge it yields not only elicits more of the world, it elicits more of us. In waiting on the world in this way, applying time and strategic patience in the spirit of invitation, we draw out and are drawn out in turn. As the Latin root of attention suggests, as we extend ourselves into the world by attending to it, we may also find that we ourselves are also extended, that is to say that our consciousness is stretched and deepened.

Here is Carr’s response, which ends his own essay and which I quote at length:

Even as I find Sacasas’s essay inspiring, I find it troubling. The way he frames the contemplative gaze as a means of re-enchantment makes me uncomfortable. An enchanted world is, by definition, a world that presents a false front to us — a front composed of what Sacasas terms, at the end of his essay, “mere things.” To see what’s really there in an enchanted world, you need to see beyond or through the surface. You need to discover what’s hidden, what’s concealed, by the merely material form, and that requires something more than sensory perception. It requires extrasensory perception. In this framing, the contemplative gaze is not just unlocking what lies untapped within us — the powers of perception, imagination, interpretation — but also exposing some spiritual essence that lies hidden within the object of the gaze.

The issue I take with Sacasas’s essay is not a matter of sense — I’m pretty sure we’re talking about the same perceptual phenomenon — but of wording. When he suggests that “enchantment is just the measure of the quality of our attention,” he’s muddying the waters. When we look at the quality of attention demonstrated by Heaney, Muñoz, and Hawthorne, we’re not seeing enchantment. We’re seeing an exquisite openness to the real. A sense of wonder does not require a world infused with spirit. The world as it is is sufficient. The reason the wording matters here is simple. What bedevils our perceptions today isn’t a lack of enchantment. It’s a lack of reality.

“Things change according to the stance we adopt towards them, the type of attention we pay to them,” Iain McGilchrist wrote in The Master and His Emissary. He’s right, but it’s important to recognize that the changes take place in the mind of the observer not in the things themselves. The things, whether works of art or of nature, have a material integrity that’s independent of our own thoughts and desires, and the stance we adopt toward them should entail a respect for that integrity.

The desire to re-enchant the world may seem like an act of humility, a way of paying tribute to the world’s unseen powers, but really it’s the opposite, an act of hubris. In demanding that the world hold greater meaning for us, that it be a reservoir for the fulfillment of our own spiritual yearnings, we are attempting yet again to impose our will on the world, to turn its myriad material forms to our own purposes, to make it our mirror. Whatever enchantment may once have been, re-enchantment is a power play.

It’s interesting that, in the English language, we have enchantment, disenchantment, and re-enchantment. What we don’t have is unenchantment. A state of disenchantment is by definition a state of loss, one that begs to be remedied by a process of re-enchantment. A state of unenchantment presumes no loss and requires no remedy. It is a state that is entirely happy with the thinginess of things. So let me, by fiat, introduce unenchantment into the language. And let me suggest that the contemplative gaze is best when it is an unenchanted gaze.

There is much to unpack here. Before I respond, let me be clear that nothing whatsoever hangs on the use, retention, or recovery of the term “enchantment” and its many variations. This entire conversation could be held, and all that technologists, philosophers, critics, and theologians want to say about it could be said, without Weber’s Entzauberung or any of its translations. Weber, for his part, was seeking to offer a sociological description of an epochal cultural change. Whatever the merit of his description, neither the concept nor the term nor its denial bears on the substance of the arguments that Sacasas and Carr make above.

I take Carr to be taking issue with a spiritually charged material reality for at least five reasons. First, it is reductive; things become “mere” things. Second, it is narcissistic; things must be what I want or need them to be to have value, in themselves or for me. Third, it is coercive; it imposes upon things what they evidently lack. Fourth, it is ungrateful; it fails to receive things as they are and thus to attend to them with the care they deserve. Finally, it is unreal; it substitutes my subjectivity for the stubborn objectivity of the thing before me. No longer am I interacting with some material item of the phenomenal world; instead, I am playing with projections upon the screen of my mind.

These are all valid and useful worries; no doubt they have a legitimate target. I don’t think Carr’s comments are an adequate response to Sacasas, however, or a successful critique of the broader view of enchanted perception that Sacasas is seeking to represent. In part there seem to be some misunderstandings between them. But perhaps more than any serious misunderstanding there is simple, unbridgeable disagreement. That disagreement, in turn, reverses the terms of the reproach: it is Carr, not Sacasas, who makes the world into a mirror.

More on that later; for now, consider definitions.

Carr opens by saying that an “enchanted world is, by definition, a world that presents a false front to us.” This is an unfortunate way to begin. Let me offer an alternative. At a minimum, an enchanted world is one that is full of life, intelligence, events, experiences, agents, and phenomena that exceed the capacity of secular, instrumental reason—especially the “hard” sciences—to measure, name, calculate, contain, control, or grasp. For Christians, the word for such a world is simply “creation.” But creation is not a false front. There may be more than what you or I can measure or glimpse, but there is not less. Creation is artifice in the sense that there is an artificer; it is not artifice in the sense that it is a façade.

Carr writes: “When we look at the quality of attention demonstrated by Heaney, Muñoz, and Hawthorne, we’re not seeing enchantment. We’re seeing an exquisite openness to the real. A sense of wonder does not require a world infused with spirit. The world as it is is sufficient.” These claims are all question-begging. What if openness to the real discloses to one’s awareness a deeper reality than one previously supposed to be true or possible—a reality not limited to one’s consciousness but objectively existent in the very thing one is contemplating, antecedent to one’s act of contemplation? Whether wonder requires a world infused with spirit is beside the point; it’s a hypothetical we aren’t in a position to answer. The question instead is whether this world is in fact suffused with spirit. To call a spirit-less world “the world as it is” begs the question, therefore, because we cannot and do not know a priori that the world lacks spirit, or that the spirit it manifests to so many in such a variety of ways is contained without remainder in the mind.

Carr is right to insist on respecting the integrity of the things of the world and of the world itself. Things aren’t playthings, and when we reduce the former to the latter both we and they are diminished as a result. So let me avoid the generic and embrace the particular. What follows is a specifically Christian account of why, in Gerard Manley Hopkins’ words, seeing the world as charged with the grandeur of God is not a failure to attend to the thisness of things.

Hopkins is a good person to start with, as it happens, given his emphasis on “inscape” or the proper “thisness” of created things, drawing on John Duns Scotus’s haecceitas. Each thing is just what it is; it isn’t anything else. It is the particular thing God made it to be, and it is this precisely in virtue of its relation to God the Creator, to his creative power and good pleasure. To, in a word, his delight.

The doctrine of creation extends this notion to anything and everything in existence. Material objects, then, are not windows we will one day raise (much less smash) in order to see “true” reality more clearly. Nor are they akin to Wittgenstein’s ladder, necessary to climb but kicked over once used. Nor still are they masks donned to deceive us or allegories that, in pointing to what they are not, exhaust themselves in their reference (somewhat like the self-destructing tapes of Mission: Impossible fame).

No, the Christian doctrine of creation teaches that the surfaces of the world contain depths and that seemingly silent things have a voice. They speak. They sing, in fact. Reality, in the words of Albert Borgmann, is eloquent. Significance in the broadest sense is therefore not only a product or property of the conscious human mind; it belongs to the things of the world prior to my contemplating them and emerge, intelligibly and fittingly, in the encounter between us.

Two concepts govern this theological perspective, each centered on the incarnation. The reason why is straightforward: the man Jesus is fully and utterly human without being merely human. He is more than human, but he is not less. Nothing in one’s phenomenal experience of Jesus’s humanity—nothing measurable by observation, analysis, or a thousand scientific tests—would tell you anything about who he is, only what he is: namely, a human being and, in that respect, like any other. Yet this man is God. Who he is is thus hidden from view.

Are we back, then, to the “false front” of Carr’s worries? By no means.

On one hand, Jesus’s humanity is not a fiction; it is not like the façades of Petra, which appear to be exteriors of magnificent temples yet contain nothing on the inside. Jesus’s humanity is, apart from sin, like yours and mine in every way. He really is a human being, and his humanity is not a temporary meat-suit he sloughs off at the Ascension. Jesus is human forever.

On the other hand, Jesus’s divinity is not opposed to his humanity. He is neither a hybrid nor a shell in which two competing principles vie for space. In all his actions, in all he says and suffers, he does so as God and man, divinely and humanly. Indeed, part of the revelation of the God-man is that God can be man without contradiction. Contra John Hick, the incarnation is not a square circle.

The most common patristic image for this reality comes from Scripture: the burning bush. The divinity of Jesus suffuses and saturates the humanity of Jesus without consuming it. This in turn came to govern the fathers’ view of the sacraments, the Eucharist above all. Anthony Domestico draws this out in a review of Paul Mariani’s biography of Hopkins:

Mariani is most affecting when describing what he calls Hopkins’s idea of “thisness—the dappled distinctiveness of everything kept in Creation.” He links Hopkins’s concept of inscape and instress to the poet’s abiding devotion to the Eucharist. Hopkins was drawn to Catholicism, Mariani suggests, through the doctrine of the Real Presence, “God dwelling in things as simple as bread and wine … the logical extension of God’s indwelling among us.” His poetry and his religion are necessary to one another: Hopkins was the poet he was because of his Catholic understanding of the Eucharist, and he was the Catholic he was because of his poetic apprehension of reality.

To be sure, the world is not a sacrament per se; a sacramental logic applies to creation in virtue of its status as created. In this way the sacraments help to explain how creation can be just what it is and, in the language of Alexander Schmemann, an epiphany of its Creator. It seems to me that Carr and other critics of (at least a certain Christian style of) enchantment substitute an “or” for the “and,” seeing the former as necessary and the latter as impossible. For Christians, it is the incarnation that demonstrates the truth and thus the possibility of the “and.”

The second concept that enters here is typology, or the use of “figure” in reading Scripture. The most famous study is Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis. He rightly argues there that the “types” or “figures” of the biblical narrative are not extinguished by their trans-local, trans-personal, trans-temporal signification. The fact that David figures Christ, or somehow mysteriously points forward to him, confirms and upholds his unique historicity; it does not obliterate it. Here is how Paul Griffiths puts it:

One event or utterance figures another when, while remaining unalterably what it is, it announces or communicates something other than itself. Eve’s assent to the tempter and her consequent taking of the forbidden fruit from the tree figures, in this sense, Mary’s fiat mihi in response to the annunciation and the consequent incarnation of the Lord in her womb. The second event—the figured—encompasses and includes the first, without removing its reality. The first—the figuring—has its reality, however, by way of participation in the second. This is in the order of being. Ontological figuration may, however, be replicated at the level of the text, and in scripture it inevitably is.

Put bluntly, figuralism falls apart if the human figures of history recorded by Scripture are neither truly human nor truly historical. It is exactly in their three-dimensional, irreducible humanity and historicity—their personal haecceity—that they “figure” Christ in advance of his advent. Saint Augustine writes in De Doctrina Christiana that humans signify with signs but God signifies with both signs and things. Salvation history, inscribed in Scripture, is thus the grand narrative of all creation, at once told by humans through written signs and told by God through created things—including the lives of human beings themselves, both their words and their deeds.

In sum, both typology and sacramentology manifest the logic embodied in the incarnation: a simultaneous affirmation of the goodness and thisness of creation in all its parts and of creation’s capacity to communicate, signify, or otherwise mediate depths of reality not immediately evident on the surface of things. “Re-enchantment,” as I see it, is one way to describe a Christian reassertion or recovery of this way of understanding and inhabiting the world. Carr acknowledges that such re-enchantment “may seem like an act of humility, a way of paying tribute to the world’s unseen powers, but really it’s the opposite, an act of hubris.” Why? “In demanding that the world hold greater meaning for us, that it be a reservoir for the fulfillment of our own spiritual yearnings, we are attempting yet again to impose our will on the world, to turn its myriad material forms to our own purposes, to make it our mirror. Whatever enchantment may once have been, re-enchantment is a power play.”

Whatever the truth of this critique applied to other types of (re-)enchantment, I hope I’ve made clear by now why it doesn’t apply to the Christian variety. Christian attention to the world and to things as the creation of God makes no demands, imposes no extrinsic meaning, bends nothing to our will to power or pleasure. It is a response (bottom up) to what we discover the world and its things to be, in themselves apart from and prior to us, just as it is a quest (top down) to see the world and its things as we have been told by God they in fact are. In the words of Psalm 19:

The heavens are telling the glory of God;

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours forth speech,

and night to night declares knowledge.

There is no speech, nor are there words;

their voice is not heard;

yet their voice goes out through all the earth,

and their words to the end of the world. (vv. 1-4)

The claim of the psalmist is that, in reality, the voice-that-is-no-voice and the words-that-are-no-words speak—are speaking, at all times, even now—whether or not we have ears to hear them. We do not imagine or construct what they say; we hearken to what they have to say to us. This is why Wendell Berry is so obstinate in his unfashionable insistence that the meaning humans find, whether in art or in the natural world, is just that: discovered, not created. Franz Wright captures the point well in his poem, “The Maker”:

The listening voice, the speaking ear

And the way, always, being

a maker

reminds:

you were made.

Berry himself puts it this way in a 1987 essay:

[Consider the concept] of artistic primacy or autonomy, in which it is assumed that no value is inherent in subjects, but that value is conferred upon subjects by the art and the attention of the artist. The subjects of world are only “raw material.” As William Matthews writes in a recent article: “A poet beginning to make something need raw material, something to transform.” For Marianne Moore, he says,

subject matter is not in itself important, except that it gives her the opportunity to speak about something that engages her passions. What is important instead is what she can discover to say.

And he concludes:

It is not, of course, the subject that is or isn't dull, but the quality of attention we do or do not pay to it, and the strength of our will to transform. Dull subjects are those we have failed.

This apparently assumes that for the animals and humans who are not fine artists, who have discovered nothing to say, the world is dull, which of course is not true. It assumes also that attention is of interest in itself, which is not true either. In fact, attention is of value only insofar as it is paid in the proper discharge of an obligation. To pay attention is to come into the presence of a subject. In one of its root senses, it is to “stretch toward” a subject, in a kind of aspiration. We speak of “paying attention” because of a correct perception that attention is owed—that, without our attention and our attending, our subjects, including ourselves, are endangered.

Mr. Matthews’ trivializing of subjects in the interest of poetry industrializes the art. He is talking about an art oriented exclusively to production, like coal mining. Like an industrial entrepreneur, he regards the places and creatures and experiences of the world as “raw material,” valueless until exploited.

Such an approach to “things” is, I recognize, just what Carr opposes. But the irony, and therefore the danger, is that Carr’s approach threatens to join hands with Matthews against Berry—as well as against Borgmann, Schmemann, Augustine, Wright, Hopkins, and Sacasas. (A formidable crew!)

Recall Carr’s modification of McGilchrist’s claim, “Things change according to the stance we adopt towards them, the type of attention we pay to them.” Carr writes, “He’s right, but it’s important to recognize that the changes take place in the mind of the observer not in the things themselves. The things, whether works of art or of nature, have a material integrity that’s independent of our own thoughts and desires, and the stance we adopt toward them should entail a respect for that integrity” (emphasis mine). It is crucial to see that the last sentence is a non sequitur. Enchanted, disenchanted, and unenchanted alike agree that all things possess a certain integrity (material and otherwise) independent of our thoughts and desires and that our relation to things ought to show respect for that integrity.

As a result, however, does Carr’s proposal not end up throwing us back into the cage of consciousness? Are not things thereby reduced to a mirror, in which we see not things but our thoughts about things? Are not things now become playthings in the inner theater of the imagination? So that I am no longer contemplating the thisness of what lies before me, but projecting it from a variety of angles—with countless filters and settings tried and tested—on the screen of my mind?

Consider Carr’s own words:

To see what’s really there in an enchanted world, you need to see beyond or through the surface. You need to discover what’s hidden, what’s concealed, by the merely material form, and that requires something more than sensory perception. It requires extrasensory perception. In this framing, the contemplative gaze is not just unlocking what lies untapped within us — the powers of perception, imagination, interpretation — but also exposing some spiritual essence that lies hidden within the object of the gaze. (emphasis mine)

So far as I can tell, the last sentence puts the shoe on the other foot. With respect to the contemplative gaze, what Carr seems to want is not for the conscious human mind to encounter an object as it is, much less to penetrate to its inexhaustible depths, but to double back on itself, thereby “unlocking what lies untapped within us—the powers of perception, imagination, interpretation” (emphasis, again, mine). It follows that, for Carr, “unenchanted” contemplation is not finally about the object in its independent objectivity but about the subject exercising his unfathomably creative subjective powers. Perception is turned inside out. Attention transforms into solipsism, even narcissism. What I see is ultimately about me, the one seeing, and what I choose or want to see. What is important is no longer the object interpreted but the change induced in the interpreter by his powers of interpretation.

This epistemic loop is just what Sacasas was worried about in his original essay. Following the work of Jane Bennett, Sacasas writes that we find ourselves “trapped in a vicious circle. Habituated against attending to the world with patience and care, we are more likely to experience the world as a mute accumulation of inert things to be merely used or consumed as our needs dictate.” He goes on:

And this experience in turn reinforces the disinclination to attend to the world with appropriate patience and care. Looking and failing to see, we mistakenly conclude there was nothing to see.

What is there to do, then, except to look again, and with care, almost as a matter of faith, although a faith encouraged by each fleeting encounter with beauty we have been graced to experience. To stare awkwardly at things in the world until they cease to be mere things. To risk the appearance of foolishness by being prepared to believe that world might yet be enchanted. Or, better yet, to play with the notion that we might cast our attention into the world in the spirit of casting a spell. We may very well conjure up surprising depths of experience, awaken long dormant desires, and rekindle our wonder in the process. What that will avail, only time would tell.

Carr is understandably worried that the “mere” in “mere things” suggests that things as they are are inadequate unless and until we impose on them a higher meaning suited to our needs, a weightier significance than they themselves can bear. Such an imposition both weighs them down and occludes their actual significance. What Sacasas has in mind, though, is the “raw material” of “industrial art,” the instrumental reason that sees things as nothing more than what they appear to be, nothing more, therefore, than their constituent elements. On such a view, what a thing is is what it is made of, which is only one step away from the constructivist view that what a thing is is whatever I make of it. In the words of David Graeber, “The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something we make and could just as easily make differently.”

Sacasas is right to delineate an alternative. I don’t know whether he’d called it the Christian alternative, but I will. I’ve spent many words outlining it in detail, so let me close here by summarizing it by contrast to both Graeber and Carr.

Regarding Graeber, his radical constructivism fails to approach and attend to the world in its thisness, in its independence and integrity apart from and prior to us, and for this reason fails to receive it as the gift that it is. With this critique I think Carr is in agreement.

As for Carr, however, his own view falls between two stools. Theoretically, it lacks sufficient metaphysical grounding to anchor reality—both its thisness and its givenness—while practically, it terminates in a contemplation that is curved in on itself. Whether the result is modern in a Kantian mode or postmodern in a Graeberian mode matters little.

To be clear, my claim is not that Christians alone can or do attend to the world as it is or that Christian enchantment (what I’m calling the church’s doctrine of creation) is the only viable, coherent, or dominant version on offer. It is instead that Carr’s critique falls short in relation to a properly Christian account of creation, contemplation, and haecceity. And it is this account that I understand Sacasas to be explicating and defending in his recommendation of seeing the world as always already enchanted, if only we take the time to pay it the attention it deserves.

On the speech of Christ in the Psalms

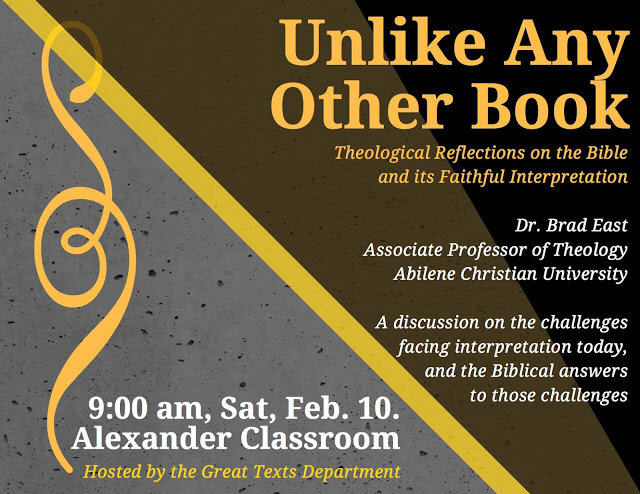

Tomorrow morning I am giving a lecture to some undergraduate students at Baylor University; the lecture's title is "Unlike Any Other Book: Theological Reflections on the Bible and its Faithful Interpretation." The lecture draws from four different writings: a dissertation chapter, a review essay for Marginalia, an article for Pro Ecclesia, and an article for International Journal of Systematic Theology.

As every writer knows, reading your own work can be painful. There's always more you can do to make it better. But sometimes you're happy with what you wrote. And I think the following quotation from the IJST piece, especially the final paragraph, is one of my pieces of writing I'm happiest about. It both makes a substantive point clearly and effectively, and does so with appropriate rhetorical force. Not many of you, surely, have read the original article; so here's a sample taste:

"[S]ince the triune God is the ecumenical confession of the church, it is entirely logical and defensible to read, say, the Psalms as the speech of Christ, or the Trinity as the creator in Genesis 1, or the ruach elohim as the very Holy Spirit breathed by the Father through the Son. Perhaps some Christian biblical scholars will respond that they do not protest the ostensible anachronism of such claims, but nonetheless hesitate at encouraging it out of concern for the humanity of these texts, that is, their human and historical specificity. In my judgment, this is a well-meant but misguided concern...

"[T]he motivations behind the concern for the humanity of Scripture are often themselves theological, but these are frequently underdeveloped. A chief example is the ubiquity in biblical scholarship of a kind of reflexive philosophical incompatibilism regarding human and divine agency, rarely articulated and never argued, such that if humans do something, then God does not, and vice versa. More specifically, on this view if Christ is the speaker of the Psalms, then the human voice of the Psalter is crowded out: apparently there’s only so much elbow room at Scripture’s authorial table. And thus, if it is shown—and who ever doubted it?—that the Psalms are products of their time and place and culture, then to read them christologically is to do violence to the text. At most, for some Christian scholars, to do so is, at times, allowable, especially if there is warrant from the New Testament; but it is still a hermeneutical device, in a manner superadded or overlaid onto a more determinate, definitive, historically rooted original.

"But the historic Christian understanding of Christ in the Psalms is much stronger than this qualified allowance, and the principal prejudice scholars must rid themselves of here is that, at bottom, ‘the real is the social-historical.’ On the contrary, the spiritual is no less real than the material, and the reality of God is so incomparably greater than either that it is their very condition of being. All of which bears two consequences for the Psalms. First, God’s speech in the Psalms in the person of the Son is not in competition with the manifold human voices of Israel that composed and sung and wrote and edited the Psalter. God is not an item in the metaphysical furniture of the universe; one and the same act may be freely willed and performed by God and by a human creature. This is very hard to grasp consistently, and it is not the only Christian view of human and divine action on offer. Nonetheless it is crucial for making sense of both the particulars and the whole of what Scripture is and how it works.

"Second and finally, to read the Psalms as at once the voice of Israel and the voice of Israel’s Messiah is therefore not to gloss an otherwise intact original with a spiritual meaning. Rather, it is to recognize, following Jason Byassee’s description of Augustine’s exegetical practice, the ‘christological plain sense.’ This accords with what is the case, namely, that ontologically equiprimordial with the human compositional history of the texts is the speech of the eternal divine Son anticipating and figuring, in advance, his own incarnate life and work in and as Jesus of Nazareth. When Jesus uses the Psalmists’ words in the Gospels, he is not appropriating something alien to himself for purposes distinct from their original sense; he is fulfilling, in his person and speech, what was and is his very own, now no longer shrouded in mystery but revealed for what they always were and pointed to. The figure of Israel sketched and excerpted in the Psalms, so faithful and true amid such trouble from God and scorn from enemies, is flesh and blood in the person of Jesus Christ, and not only retrospectively but, by God’s gracious foreknowledge, prospectively as well. It turns out that it was Christ all along."

Diarmaid MacCulloch on the Psalter as the secret weapon of the Reformation

"The explanation for this mass lay activism may lie in the one text which the Reformed found perfectly conveyed their message across all barriers of social status and literacy. This was the Psalter, the book of the 150 Psalms, translated into French verse, set to music and published in unobtrusive pocket-size editions which invariably included the musical notation for the tunes. In the old Latin liturgy the psalms were largely used in monastic services and in private devotional recitation. Now they were redeployed in Reformed Protestantism in this metrical form to articulate the hope, fear, joy and fury of the new movement. They became the secret weapon of the Reformation not merely in France but wherever the Reformed brought new vitality to the Protestant cause. Like so many important components of John Calvin's message, he borrowed the idea from the practice of Strassburg in the 1530s. When he arrived to minister to the French congregation there after his expulsion from Geneva in 1538, he found the French singing these metrical psalms, which has been pioneered by a cheerfully unruly convert to evangelical belief, the poet Clément Marot. Calvin took the practice back to Geneva when he returned there to reconstitute its Reformation. Theodore Beza finally produced a complete French metrical psalter in 1562, and during the crisis of 1562–3, he set up a publishing syndicate of thirty printers through France and Geneva to capitalize on the psalm-singing phenomenon: the resulting mass-production and distribution was a remarkable feat of technology and organization.

"The metrical psalm was the perfect vehicle for turning the Protestant message into a mass movement capable of embracing the illiterate alongside the literate. What better than the very words of the Bible as sung by the hero-King David? The psalms were easily memorized, so that an incriminating printed text could rapidly be dispensed with. They were customarily sung in unison to a large range of dedicated tunes (newly composed, to emphasize the break with the religious past, in contrast to Martin Luther's practice of reusing old church melodies which he loved). The words of a particular psalm could be associated with a particular melody; even to hum the tune spoke of the words of the psalm behind it, and was an act of Protestant subversion. A mood could be summoned up in an instant: Psalm 68 led a crowd into battle, Psalm 124 led to victory, Psalm 115 scorned dumb and blind idols and made the perfect accompaniment for smashing up church interiors. The psalms could be sung in worship or in the market-place; instantly they marked out the singer as a Protestant, and equally instantly united a Protestant crowd in ecstatic companionship just as the football chant does today on the stadium terraces. They were the common property of all, both men and women: women could not preach or rarely even lead prayer, but they could sing alongside their menfolk. To sing a psalm was a liberation—to break away from the mediation of priest or minister and to become a king alongside King David, talking directly to his God. It was perhaps significant that one of the distinctive features of French Catholic persecution in the 1540s had been that those who were about to be burned had their tongues cut out first."

—Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (Penguin Books: 2003), 307–308