Resident Theologian

About the Blog

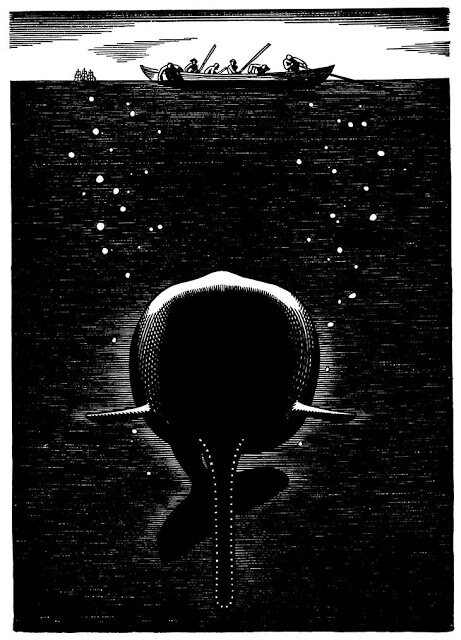

On Moby-Dick

I finally did it. Last month I read Herman Melville's Moby-Dick.

It would be an understatement to say that I loved it. I fell in love. And with all of it: the prose, the themes, the characters, the plot, the figural saturation, the endless and endlessly digressive chapters, the sheer American mythic theogony of it.

When one commits to read such heralded classics, there's always the question lingering in the back of one's mind whether it will prove a crushing disappointment. Like meeting one's heroes, reading the canon is not always for the faint of heart.

No such disappointment with Moby-Dick. Since I started it, and especially since I finished it, I have been an annoying pest to anyone and everyone who will listen to me sing of its greatness, some 170 years since its writing.

The air one breathes while reading Melville is rare. It's the same air one discovers blowing through Shakespeare, Dante, Milton, Dostoevsky, Virgil, Homer. After reading such authors, one understands the true meaning of such over-used terms like "classic," "genius," and "master." They are a class unto themselves.

Reading Melville's writing in Moby-Dick is like reading Shakespeare, only if he were an American and wrote prose. It's poetry in long-form and without line breaks. Melville did not know how to write an uninteresting sentence. The cavalcade of words builds and builds until it becomes a vast and imposing army in flawless formation, executing whatever order of subtle wit or penetrating insight Melville deigned to issue.

Did I mention he's funny? Laugh out loud funny. Every sentence in the book could be underlined, every third paragraph circled and starred, every fifth excerpted in an anthology of nothing but samples of perfect instances of American English construction.

I got bit by the theology bug early in my teens. I was dead set on my discipline from an early age. But had I read Moby-Dick at the same age, they might have gotten me instead. I mean language and lit: I might have been bound for English departments, buried beneath a rubble of 19th century manuscripts, for the rest of my life. Indeed, what makes a classic a classic, and therefore what makes Melville's opus a classic, is its inexhaustible character. Upon closing the final page, I could imagine dedicating my life to this book and this book alone. Its riches are bottomless.

Yet the one thing I can't imagine is having anything original to say about such a widely interpreted and commented-upon book. Even these reflections are little more than modest variations on the same ringing theme common to thousands upon thousands of American readers since the centenary of Melville's birth in 1919. But I'm hungry for more. I already read Nathan Philbrick's Why Read Moby-Dick? Here's to more where that came from, and above all, to many, many, many re-readings of that great mythic tome—that oceanic mishmash of Qoheleth and the Book of Job—that biblical pastiche of the enduring American soul—the undoubted and unrivaled great American novel—the one, the only, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale.