Resident Theologian

About the Blog

A test for exegesis

Is God merely a character within the text? Or also an author of the text? The difference matters for scriptural interpretation.

A simple test for any proposed reading of Scripture, but especially for those put forth by biblical scholars:

Is God understood as (presupposed to be) a living agent…

(a) within the world described by the text, whatever its genre? or

(b) both within the world of the text and behind, in, and through the text itself?

In other words, is God a character in the text? an author of the text? or both?

What I find, in far too much Christian scholarship on the Bible, is option (a). God is taken seriously as a character, an agent, a force, a presence, an actor, a protagonist—within the narrative or poetry or whatever pericope or canonical book. Apparently, for many Christian biblical scholars, that is what it means to read “theologically.” The modifier “theological” denotes a “more than humanist” or “non–methodological atheist” hermeneutic; God is not presumed to be a superstition best elided in interpretation. This principle might extend to the present, so that the God at work in the world of the text is taken to be at work in the world of the reader.

But a crucial premise has been overlooked or denied. To read in the way thus delineated is to read the Bible “like any other book,” as if its form and content, its status, were no different in kind from any other work of literature. But why, then, should you or I or the scholar give it our attention, indeed a unique attention incomparable to any other book? The answer is simple: Because, as the church confesses, what the Bible mediates or bears to us is “the word of the Lord.” The Lord God of Israel stands behind the words of the text that attest him. They are inspired by him; he is, in the phrase of St. Thomas Aquinas, their “principal author.”

If that is true—and its truth is a matter of faith, not demonstration—then it must, and invariably will, affect how one reads the text. Nor is there anything unscholarly about this. Method is apt to subject matter. The subject matter of Christian exegesis of canonical Holy Scripture is the living word of the living God to his living people: the speech of Christ to his body and bride, in the present tense.

Christian scholars should read it as such. Bracketing the text’s inspiration or divine authorship is a dodge. A reading that limits God to intratextual agent while ignoring God’s role as extratextual author is not yet theological in the fullest sense.

Exegetes, take note.

The problem with evangelicalism

There’s not only one, granted. But this isn’t one of those posts. It’s not a beat-up-on-the-evangelicals manifesto in nine parts. It’s not about evangelicals and politics, or about that popular Christianity Today podcast, or about which marks truly define an evangelical, and whether they ought to be doctrinal or sociological or other. This is a minor little comment about theology and hermeneutics. Here it is.

There’s not only one, granted. But this isn’t one of those posts. It’s not a beat-up-on-the-evangelicals manifesto in nine parts. It’s not about evangelicals and politics, or about that popular Christianity Today podcast, or about which marks truly define an evangelical, and whether they ought to be doctrinal or sociological or other.

This is a minor little comment about theology and hermeneutics. Here it is.

Evangelicalism isn’t merely a style (a way of being Christian) or a worldview (a set of beliefs). It’s a hermeneutic. It’s a path from here to there, a map for movement, a manual for drawing conclusions and making judgments about what Christian faith is, what Christian behavior entails, and how to inhabit the world. That manual occasionally takes written form but it usually operates in unwritten circulation, imbibed like mother’s milk from (successful) catechesis in active involvement in evangelical churches.

The substance of that manual may be summarized in a slogan: nuda scriptura. That is:

the Bible alone is for Christians the one encompassing and all-purpose practical guide to faith, ethics, politics, and culture;

the individual Christian is equipped and encouraged (perhaps required) to use the Bible in order to discover its normative teaching and guidance for him or herself regarding matters of doctrine and morals;

in principle no one and nothing—no person (a fellow Christian) or office (a pastor) or institution (a church) or text (past tradition)—is either better equipped or more authoritative with respect to reading the Bible for its normative teaching on doctrine and morals than the living baptized individual adult believer;

whatever the Bible does not speak about in clear, direct, and explicit terms is for Christians adiaphora.

Let me remind you again that few evangelical scholars would endorse this hermeneutic as a positive proposal. But it is unquestionably the default setting for numberless evangelical believers, churches, and institutions. And the main point I want to make here is that that is a feature, not a bug. Moreover—and this is the kicker—to cease to believe in and act according to this hermeneutic is in a real sense to cease being evangelical, at least as that term is embodied and enacted in concrete communities and the society at large.

This is why, for example, so many evangelicals who ostensibly remain evangelicals while earning graduate degrees and teaching in institutions of higher education no longer attend the kinds of churches in which they were raised but worship instead in Anglican or similarly liturgical traditions. Their on-the-page beliefs (inerrancy, sola scriptura, virginal conception, bodily resurrection, traditional marriage) remain the same, but the outward devotional and liturgical expression of those beliefs is different, indeed necessarily different, rooted as those external practices are in a crucial hermeneutical transformation.

So far I’m merely offering a description. This isn’t a critique. The title of this post, however, refers to a “problem.” Here’s the problem as I see it.

There are people who were raised evangelical and still claim, or at least do not repudiate, the title. But such people have migrated away from the evangelical hermeneutic in their studies, their experiences, their teaching and writing, and/or their ecclesial home. Nevertheless they still aim to speak to and for, if not on behalf of, evangelicals. They seek to persuade evangelicals to believe this or that, or reject this or that. Having unlearned or let go of the evangelical hermeneutic, though, they no longer speak from and to that hermeneutic; they don’t argue according to its premises; they write by different premises, rooted in a different hermeneutic.

Always—and I do mean always—the result is a failure to communicate (not to mention to persuade). The message is lost in translation. The speaker and listener, the author and reader, simply talk past each other. For they are not speaking the same language. They no longer share enough in common for their disagreements to be intelligible. Instead, their disagreements are an inevitable function of differing first principles, in this case, opposed hermeneutics of Christian faith and theology with respect to Holy Scripture.

Yet rather than this situation being seen as both obvious and unavoidable, the tenor of the constant miscommunication is, on both sides, rancor, distrust, and endless anathemas. I’m not so much concerned right now with the folks on the receiving end, those who still hold to the evangelical hermeneutic. I’m concerned with those who’ve lost or rejected that hermeneutic but who continue to speak to those who hold it.

It should be neither surprising nor frustrating if, should I say, “We as Christians ought to believe X doctrine because Y saint or Z tradition teaches it,” the response from a true-blue evangelical is, “Why should I care what Y or Z say? I don’t see X taught clearly, directly, and explicitly in the Bible.” For you are not seeking to persuade on the terms held by your listener or reader. The latter senses intuitively that what you are really asking him or her is to stop being the sort of evangelical they are, i.e., you are asking them to give up the evangelical hermeneutic. That may be a worthy endeavor—almost everything I’ve written as a scholar is in service to that endeavor—but that is a different task than making an argument by and for and among a certain community, on the terms set and shared by that community, that presupposes that those very terms, which in turn define that community, are wrong on principle. It’s a bait and switch, intended or not.

Furthermore, it’s important to see that you can’t have your cake (evangelical hermeneutic) and eat it too (sacred tradition). There are plenty of traditional doctrines that are plausibly compatible with the evangelical hermeneutic; there are fewer of them that follow, logically and necessarily, therefrom. Take divine simplicity, or the eternal generation of the Son, or the perpetual virginity of Mary, or even the creeds of Nicaea and Constantinople. None of these is incompatible with the plain teaching of Scripture. Can each and every one, in each and all of its details, be generated (1) directly from scriptural exegesis (2) to the exclusion of all other interpretive options (3) in accordance with the evangelical hermeneutic? I’m not so sure.

Which is why evangelicalism is such a rambunctious, fractious collective. It’s built for incessant, indefinite dissent. Someone or someones will always raise an objection, and precisely in accordance with the rules for assent and consent stipulated by the evangelical hermeneutic.

Biblicism is a woolly, ungovernable thing. It has a life of its own, because (among other reasons) it empowers individuals to interpret the text for themselves, with unpredictable results undecided in advance of reading, discussion, and debate.

In my view, for those who would remain in the evangelical family, you have to choose. You can be a biblicist, and stay; or you can stop being a biblicist, and leave. The sharpness of that choice need not be a matter of literal church membership. But theologically speaking, in terms of ideas and writing and how we make arguments and to whom and according to what premises, it seems to me that the choice is indeed just that sharp. It’s one or the other. There is no third way.

Axioms of Christian exegesis

I … rejoice, as any interpreter of scripture should, to find such a clear case of prima facie contradiction [in the text]; such instances are efficacious in prompting theological thought because of the axiom that the canon of scripture is not incoherent.

I … rejoice, as any interpreter of scripture should, to find such a clear case of prima facie contradiction [in the text]; such instances are efficacious in prompting theological thought because of the axiom that the canon of scripture is not incoherent. …

But what about the pleonasm [in the biblical passage under consideration]? It’s axiomatic for Christians that the text of scripture has no accidental features, which entails that the pleonasm isn’t one.

—Paul J. Griffiths, Regret: A Theology (University of Notre Dame Press, 2021), 4, 20

Publication round-up: recent pieces in First Things, Journal of Theological Interpretation, Mere Orthodoxy, and The Liberating Arts

I've been busy the last month, but I wanted to make sure I posted links here to some recent pieces of mine published during the Advent and Christmas seasons.

I've been busy the last month, but I wanted to make sure I posted links here to some recent pieces of mine published during the Advent and Christmas seasons.

First, I wrote a meditation on the first Sunday of Advent for Mere Orthodoxy called "The Face of God."

Second, I interviewed Jon Baskin for The Liberating Arts in a video/podcast called "Can the Humanities Find a Home in the Academy?" Earlier in the fall I interviewed Alan Noble for TLA on why the church needs Christian colleges.

Third, in the latest issue of Journal of Theological Interpretation, I have a long article that seeks to answer a question simply stated: "What Are the Standards of Excellence for Theological Interpretation of Scripture?"

Fourth and last, yesterday, New Year's Day, First Things published a short essay I wrote called "The Circumcision of Israel's God." It's a theological meditation on the liturgical significance of January 1 being simultaneously the feast of the circumcision of Christ (for the East), the solemnity of Mary the Mother of God (for Rome), the feast of the name of Jesus (for many Protestants), and a global day for peace (per Pope Paul VI). I use a wonderful passage from St. Theodore the Studite's polemic against the iconoclasts to draw connections between each of these features of the one mystery of the incarnation of the God of Israel.

More to come in 2021. Lord willing it will prove a relief from the last 12 months.

On finding race and racism in the New Testament

I am skeptical of attempts to center contemporary Christian conversations about race on New Testament texts purported to feature or critique racism. From what I can tell, this move is a common one. Pericopes adduced include Jesus's encounter with the Syro-Phoenician woman, his meeting with the Samaritan woman at the well, and the parable of the good Samaritan. Most often, however, I see writers, pastors, and preachers use the example of gentiles in the early Jewish church, deploying some combination of Acts 15, Ephesians 2, Galatians, and Romans in order to illustrate the ostensible overcoming of racism in the early Jesus movement as an abiding example for churches struggling with the same problem today.

Why am I skeptical of this move? Let me try to spell out my reasons succinctly.

1. Race is a modern construct. What we mean by "race" does not exist in the New Testament, either as a concept or as a narratively depicted phenomenon.

2. Racism, therefore, also does not exist in the New Testament. I'm a defender of theological anachronism in Christian exegesis of Scripture, but speaking of "racism in the New Testament" is the worst kind of anachronism. It's a projection without a backdrop, a house built on sand, a conclusion in search of an argument.

3. Prejudice toward, suspicion of, and stereotyping of persons from other communities—where "other" denotes differences in region, language, cult, class, or scriptural interpretation—did exist in the eastern Mediterranean world of the Roman Empire in the first century. Inasmuch as contemporary readers want to draw analogies between forms of modern prejudice and forms of ancient prejudice, as the latter is found in the New Testament, so be it.

4. It is a fearful and perilous thing, however, to attribute such prejudice to those Jews who populated the early church or who opposed it. Why? First of all, because today it is almost uniformly gentiles who make this claim, and gentile Christians have an almost ineradicable propensity to assign to Jews—past and present—sinful behavior they seek to expunge in themselves. (See also #7 and #10 below.)

5. Moreover, Jewish attitudes about gentiles in the first century were neither uniform nor simple nor reducible to prejudice. The principal thing to realize is that, according to the witness of both the prophets and the apostles (that is, the Old and New Testaments), the distinction between Jews and gentiles is a creation of God. There are Jews and gentiles because God called Abraham and all his descendants with him to be set apart as God's holy people. All those not so called, according to the flesh, are gentiles. This distinction is maintained, not abolished, in the preaching of the gospel by the Jewish apostles in the first half century of the church's existence.

6. First-century Jewish beliefs about and relations with gentiles, then, were informed by scriptural testimony. God's word—that is, the Law, the prophets, and the writings—has a lot to say, after all, about the nations (the goyim or ethne). Go read some of it. See if you walk away with a clear, obvious, and uncomplicated view about those human communities that lie outside the election of Abraham together with his seed. Focus in particular on the book of Leviticus. Then go read chapter 10 of the book of Acts. Is St. Peter blameworthy for his hesitancy about Cornelius and his household? Is he foolish or shortsighted, much less prejudiced? Or is he following the way the words run in the Torah until such time as an angel of the Lord Jesus provides a vision paired with a divine command to act according to an alternative and heretofore unimagined interpretation of Torah? (An interpretation, note, only possible now in the light of the resurrection of the Messiah from the dead.) I'd say it's fair to think Peter, along with his brother apostles, was not in the wrong if God deemed a vision necessary to change his mind—a vision, mind you, that is didactic, not an indictment.

(7. As a historical matter, it is also worth drawing attention to the work of scholars precisely on persons such as Cornelius, gentile God-fearers and friends and patrons of the synagogue in the diaspora. The caricature of Jews living outside the land in the first century, distributed across countless cities in the Roman Empire and elsewhere, as bitter, sectarian, resentful, fearful, and hostile ethnic fundamentalists is just that: a caricature. Indeed, one should always beware of anti-Jewish sentiment lingering just beneath and sometimes displayed right on the surface of historical scholarship as well as popularized historical treatments of the Bible.)

8. As for Acts 15—the culmination, as St. Luke tells it, of Peter's vision, of Saul's conversion, of Pentecost, of the ascension, of the birth of Jesus, in fact of the calling of Abraham and the creation of Adam—the story is hardly one of racism or even of ethnic prejudice. The question for the nascent apostolic church was not whether gentiles could join. It would certainly qualify as something akin to ethnic prejudice if the exclusively Jewish ekklesia said, "We don't want your kind here." But that's not what they said. All saw and glorified God for the wonders he'd worked among the gentiles, drawing them to faith in Jesus Messiah. The question—the only question—was on what terms they would enter, that is, by what means and in accordance with what rule of life they would become members of Christ's body. Would they, like the Jews, follow the Law of Moses? Would they honor the Sabbath, keep kosher, be circumcised? Or would they not?—that is, by remaining gentiles, not subject to Torah's statutes and ordinances. Either way, they would be saved; either way, they would believe in Jesus; either way, they would receive baptism and thereby Jesus's own Spirit. The issue, in short, was not an ethnic, much less a racial, one. The issue was the will of God for those believers in Jesus who were not descendants of Abraham. And after not a little disputation and controversy, the apostolic church discerned that it was the Spirit's good pleasure for the church to comprise Jews and gentiles both, united in the Messiah as Jew and gentile, neither becoming the other nor both becoming a third thing.

9. It turns out, therefore, that the climactic tale of gentiles being welcomed into Jewish messianic assemblies around the Mediterranean Sea in the years 30–80 AD has nothing whatsoever to do with race, racism, or ethnic prejudice. Acts 15 is simply not about that. Insinuating that it does either distorts its proper significance or metaphorizes a text without grounding, or even the need, to do so.

10. None of the foregoing is meant to suggest that either the New or the Old Testament is thus reduced to silence on pressing challenges facing the American church today, not least the seemingly unexorcisable demon of anti-black racism. Nor, as I said above, is it impossible, or imprudent, to draw analogies between scriptural instances of out-group derogation and present-day experience, or between the complications arising from Jew-gentile integration in Pauline assemblies and similar complications in American churches. Nor, finally, does the wider witness of Holy Scripture have nothing to say about the bedrock principles that ought to inform Christian speech about these matters: that God is sovereign, gracious Creator of all; that every human being is created in the image of God; that each and every human being who has ever lived is one, in St. Paul's words, "for whom Christ died." I only want to emphasize what we can and what we cannot responsibly read the canon to say. More than anything, though, I want to encourage gentile Christians to be vigilant in their perpetual war against Marcionitism in all its forms. There is a worrisome tendency in recent Christian talk about white racism in America to frame it, biblically and theologically, as anticipated and foreshadowed by Jews. Even when unintended—and I have no doubt it usually is—that is a morally noxious, canonically warped, theologically obtuse, and historically false claim. The early Jewish church did not resist gentile inclusion due to its racism against gentiles. It had none, for there was none to have. There is, lamentably, plenty of racism in the world today. Look there if you want to address it. You won't find any in the pages of the Bible.

New review in the latest issue of Christian Century

"The spiritual sense that [premodern] saints sought—which is to say, prayed for, delighted in, and contemplated—was not a 'stable' 'layer' of meaning 'residing' in the text. It was the in principle infinite sacramental signification of human signs divinely authored and illumined. For the res of scripture, as a whole and in each of its parts, is Christ. Just how any one particular text of scripture signifies Christ, not to mention just what Christ might use such a text to say to the believing reader under the Spirit’s guidance, is limited neither by human authors’ intentions nor by ordinary rules of grammar and syntax, nor by the capacities, desires, or convictions of readers, believing or pagan. It is determinate, but only insofar as Christ is determinate. And Christ makes himself present and known in endless ways on countless occasions: in the determinate elements of the Eucharist, in the determinate bodies of the faithful, in the determinate words of the sermon, in the determinate sufferings of the least of these. Just so, we should expect countless, indeed endless, manifestations of Christ on the sacred page."

Read the whole thing here.

Why there's no such thing as non-anachronistic interpretation, and it's a good thing too: reflections occasioned by Wesley Hill's Paul and the Trinity

Programmatically: The fundamental hermeneutical first principle of self-consciously historical-critical study of the Bible is that such study must avoid anachronism. Two hermeneutical values underlie or spin off this principle: on the one hand, what makes any reading good is whether it is properly historical; therefore, on the other hand, all reading of the Bible ought to avoid anachronism—or to say the same thing negatively, anachronistic readings of biblical texts are by definition bad.

Enter scholars like Hill: supple interpreters, subtle thinkers, careful writers, sophisticated theologians. What Hill aims to show in his book is that the conceptual resources of trinitarian theology may be used in the reading of biblical texts like Paul's letters as a hermeneutical lens that enables, rather than obstructs, understanding. More to the point, such understanding does not stray from the canons of historical criticism, which is to say, it does not fall prey to anachronism. Thus, his project "plays by the rules" while bringing to bear doctrinal resources otherwise considered anathema by historical critics (both Christian and otherwise).

Consider his language:

"I need to clarify in what ways the grammar of trinitarian theology will and will not be invoked, and to specify the methodological safeguards that will protect my exegesis from devolving into an exercise in imaginative theologizing." (31)

"The methodological danger that lurks here is one that may be described as a certain kind of 'projection'... To avoid this pitfall, I will adopt a twofold approach: First, the readings of Paul I will offer ... will be self-consciously historical readings, guided by the canons of 'critical' modes of exegesis. At no point will a trinitarian conclusion be allowed to 'trump' what Paul's texts may be plausibly shown to have communicated within his own context. Second, trinitarian theologies will be employed as hermeneutical resources and, thus, mined for conceptualities which may better enable a genuinely historical exegesis to articulate what other equally 'historical' approaches may have (unwittingly or not) obscured." (45)

"[Paul's theology's] patterns and dynamics may be newly illumined and realized within new contexts and by means of later conceptualities, which are to some degree 'foreign' to the texts themselves." (46)

"...the use of trinitarian theology in the task of reading Paul in an authentically historical mode..." (46)

"my goal is not to 'find' trinitarian theology 'in' Paul so much as to use the conceptual resources of trinitarian doctrine as hermeneutical aids for reading Paul afresh. [This book addresses the] question of whether those trinitarian resources may actualize certain trajectories from Paul's letters that he would have expressed in a different idiom." (104-105)

"[Recent] studies are rightly concerned to respect the linear unfolding of historical development, rather than anachronistically imposing later theologies back onto Paul's letters. But my thesis ... has been mostly taken up with demonstrating the converse: that trinitarian doctrine may be used retrospectively to shed light on and enable a deeper penetration of the Pauline texts in their own historical milieu, and that it is not necessarily anachronistic to allow later Christian categories to be the lens through which one reads Paul. ... I have tried ... to show that the conceptual categories of 'persons in relation' developed so richly in the fourth century and in the following theological era, may enable those who live with them to live more deeply and fruitfully with the first century apostle himself." (171)

"Is it possible ... that a kind of broad, pluriform trinitarian perspective, far from being an anachronistic imposition on the texts of Paul, may instead prove genuinely insightful in a fresh look at Paul?" (169)

Let me be clear: Hill masterfully demonstrates his thesis. Anyone who knows my theological interests knows that Hill is preaching to the choir. The concepts, categories, and modes of reading developed in the 4th and 5th centuries by the church fathers constitute a hermeneutic nonpareil for faithful interpretation of the Christian Bible, the epistles of Paul included. And Hill shows us why: positively, because that hermeneutic was constructed precisely in response to the kinds of challenge for talk about God, Christ, and Spirit found in Paul's letters and elsewhere; negatively, because contemporary historical critics have not learned the exegetical-theological lessons of trinitarian doctrine, and thus largely replay the terminological debates from the side of opposition to Nicaea (e.g., distinction obviates unity, derivation implies subordination, etc.).

But when I say that Hill demonstrates his thesis, I do not mean that he succeeds in offering a reading that avoids anachronism. He does not. But the fault is not with him. The fault is with the criterion itself. His only fault—and it is a minor one, but an instructive one nonetheless—is to play by the rules set for him by biblical criticism. Because the truth is that avoiding anachronism is impossible. The act of reading is itself irreducibly, unavoidably, essentially anachronistic. In particular, reading any text from the past, indeed a religious text from the ancient past, just is to engage in anachronism.

So the issue is not that Hill's trinitarian hermeneutic for Paul is anachronistic. It's that the non-trinitarian hermeneutics of every one of his peers—Dunn, Hurtado, McGrath, Bauckham, whomever—are equally anachronistic.

Hill gestures toward this fact in his critique of the use of "monotheism" as a category applied to Paul, as well as the language of a vertical axis on which to plot the relative divinity of God and Jesus. But the critique goes all the way down. And this cannot be said forcefully enough, given the depths of historical criticism's rejection of anachronism, both for its own exegesis and that of anyone else, and given the extent of its influence not only over the academy but over the church. In a word:

Historical-critical exegesis is fundamentally, inescapably anachronistic.

What do I mean by this, and on what grounds do I say it?

First, and most basically, because historical criticism is itself a contingent, lately constructed mode of reading not universally found among all communities of reading. Put differently: the attempt to read without anachronism is a parochial idea—created at a certain time and place, and therefore present in some cultures and not others. So that the suggestion that non-anachronistic reading is what it means to read well is self-refuting, if reading was ever a successful practice outside of Western culture in the last few centuries.

Second, because all reading is anachronistic, as I said above. Let's limit that claim to the readings of texts not written in one's own immediate time and place and/or addressed to oneself (i.e., not emails received moments after sending). To read a text outside of its original context and audience means to read that text in a new, different context, by or with a new, different audience—in this case, you, the reader. That means that the language, customs, assumptions, beliefs, practices, background knowledge, relationships, intentions, and so on, that pertained to the original setting of the text are no longer present, or present in the same way, and that you bring to the text entirely different customs, knowledge, experience, etc. To read a text in such a setting invariably changes how the text is read. And however much one tries to mitigate such contextual factors, resistance is futile; indeed, resistance is itself a sign of doing something different—engaging in a different practice, through different means, with a different end—than the original audience in its original context.

Now, third, the objection might arise: Does that mean we simply cannot arrive at historical understanding? Not at all. My point is the opposite: True historical understanding is always anachronistic. Because historical self-understanding, historical consciousness, is itself a historical achievement, a contingent event. The way that we late moderns "think" history is not native to history's actors; "putting ourselves in their shoes," trying to think their thoughts after them, in just the way they thought them, ruthlessly identifying and trying to eliminate any stray intrusions of modern thoughts and even modern applications—that is, strictly speaking, something our forebears did not do. We can do it, we can play the game, but it's a game we're playing (just like chess or basketball, which are real games with real rules we can really play in the present, but which have not always existed, even if analogous games existed in other cultures, past or present); it's not a sort of time machine of the mind. Even that metaphor fails, since the trouble with time machines, as with observation of nature, is that they don't leave the past untouched. The same goes for historical investigation. You bring the future with you.

Fourth, the insight of Gadamer is key here: Historical understanding is a possibility, but lack of anachronism is neither possible nor desirable. That would entail leaping over the history in between the text in question and the present. But that history has, quite literally, made the reading of that text now, in this setting, possible; furthermore, texts bring with them the histories of their reception that have attended them ever since their inception. Those histories not only inform our interpretations in the present, however historically rigorous: they set the conditions for them. To make the claim, "Paul's conception of God and Christ is binitarian," is to locate oneself on a timeline; it is not a claim that was made, because it could not have been made, prior to a certain moment in our history. And, as a claim, it would be no more intelligible to Paul than to Anselm. That is what makes it anachronistic.

Fifth, the most important reason why historical-critical reading is essentially anachronistic is the way that it uses—quite explicitly and without apology—resources outside the text, resources foreign to the text's original audience, as a means of interpreting the text. Examples are obvious: monographs and articles, concepts created long after the text's composition, archeological findings, data regarding life and neighboring cultures prior to and contemporaneous with the text's original setting. Historical-critical exegesis often proposes readings of ancient religious texts (say, Genesis 1) that would have been impossible in the original context, because no one at the time had, or could have had, the kind of comprehensive knowledge about their own time and place that we have since amassed. (It is worth noting that this exegetical procedure is not different in kind than reading Genesis 1 in light of the doctrine of creation ex nihilo, or scientific theories about the origins of the universe.) In a manner of speaking, the best historical-critical interpretations are self-consciously maximalist in just this way: they are so exhaustive in searching out every possible detail, contour, allusion, and influence that such an interpretation in the text's original setting would have been unthinkable—indeed, no such interpretation would have been possible until now, this very moment in time. Undertaken in that sort of self-conscious way, anachronism would be welcomed and readily admitted as the very occasion and goal of historical reading.

Much more could be said; Lord willing, I'll say it in print here in a few years. For now, recall Hill's rhetorical question in the book's conclusion: "Is it possible ... that a kind of broad, pluriform trinitarian perspective, far from being an anachronistic imposition on the texts of Paul, may instead prove genuinely insightful in a fresh look at Paul?" (169). Let me take a lesson from Hill and apply it to his own work: these are not competing claims; it is not an either/or situation. Bringing trinitarian doctrine to bear on the letters of Paul is both anachronistic and richly insightful. Whether or not it is more insightful than non-trinitarian readings, whether or not it does greater justice to the texts considered as a whole and in all their literary-theological diversity, is a separate question, one not governed exclusively by historical concerns. I happen to side with Hill's answer. But even if we were wrong in our judgment, it would not be because our reading was anachronistic. An ostensibly superior reading would be, too.

On the speech of Christ in the Psalms

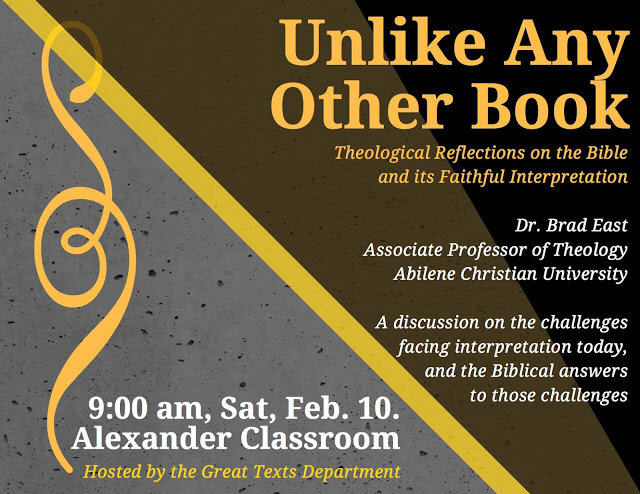

Tomorrow morning I am giving a lecture to some undergraduate students at Baylor University; the lecture's title is "Unlike Any Other Book: Theological Reflections on the Bible and its Faithful Interpretation." The lecture draws from four different writings: a dissertation chapter, a review essay for Marginalia, an article for Pro Ecclesia, and an article for International Journal of Systematic Theology.

As every writer knows, reading your own work can be painful. There's always more you can do to make it better. But sometimes you're happy with what you wrote. And I think the following quotation from the IJST piece, especially the final paragraph, is one of my pieces of writing I'm happiest about. It both makes a substantive point clearly and effectively, and does so with appropriate rhetorical force. Not many of you, surely, have read the original article; so here's a sample taste:

"[S]ince the triune God is the ecumenical confession of the church, it is entirely logical and defensible to read, say, the Psalms as the speech of Christ, or the Trinity as the creator in Genesis 1, or the ruach elohim as the very Holy Spirit breathed by the Father through the Son. Perhaps some Christian biblical scholars will respond that they do not protest the ostensible anachronism of such claims, but nonetheless hesitate at encouraging it out of concern for the humanity of these texts, that is, their human and historical specificity. In my judgment, this is a well-meant but misguided concern...

"[T]he motivations behind the concern for the humanity of Scripture are often themselves theological, but these are frequently underdeveloped. A chief example is the ubiquity in biblical scholarship of a kind of reflexive philosophical incompatibilism regarding human and divine agency, rarely articulated and never argued, such that if humans do something, then God does not, and vice versa. More specifically, on this view if Christ is the speaker of the Psalms, then the human voice of the Psalter is crowded out: apparently there’s only so much elbow room at Scripture’s authorial table. And thus, if it is shown—and who ever doubted it?—that the Psalms are products of their time and place and culture, then to read them christologically is to do violence to the text. At most, for some Christian scholars, to do so is, at times, allowable, especially if there is warrant from the New Testament; but it is still a hermeneutical device, in a manner superadded or overlaid onto a more determinate, definitive, historically rooted original.

"But the historic Christian understanding of Christ in the Psalms is much stronger than this qualified allowance, and the principal prejudice scholars must rid themselves of here is that, at bottom, ‘the real is the social-historical.’ On the contrary, the spiritual is no less real than the material, and the reality of God is so incomparably greater than either that it is their very condition of being. All of which bears two consequences for the Psalms. First, God’s speech in the Psalms in the person of the Son is not in competition with the manifold human voices of Israel that composed and sung and wrote and edited the Psalter. God is not an item in the metaphysical furniture of the universe; one and the same act may be freely willed and performed by God and by a human creature. This is very hard to grasp consistently, and it is not the only Christian view of human and divine action on offer. Nonetheless it is crucial for making sense of both the particulars and the whole of what Scripture is and how it works.

"Second and finally, to read the Psalms as at once the voice of Israel and the voice of Israel’s Messiah is therefore not to gloss an otherwise intact original with a spiritual meaning. Rather, it is to recognize, following Jason Byassee’s description of Augustine’s exegetical practice, the ‘christological plain sense.’ This accords with what is the case, namely, that ontologically equiprimordial with the human compositional history of the texts is the speech of the eternal divine Son anticipating and figuring, in advance, his own incarnate life and work in and as Jesus of Nazareth. When Jesus uses the Psalmists’ words in the Gospels, he is not appropriating something alien to himself for purposes distinct from their original sense; he is fulfilling, in his person and speech, what was and is his very own, now no longer shrouded in mystery but revealed for what they always were and pointed to. The figure of Israel sketched and excerpted in the Psalms, so faithful and true amid such trouble from God and scorn from enemies, is flesh and blood in the person of Jesus Christ, and not only retrospectively but, by God’s gracious foreknowledge, prospectively as well. It turns out that it was Christ all along."

An unpublished footnote on Longenecker on Hays on apostolic exegesis

In the “Preface to the Second Edition” (Biblical Exegesis in the Apostolic Period, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1975, 1999), xiii-xli), Longenecker responds to criticisms like mine above and those of Hays and Leithart, and engages directly with Hays (xxxiv-xxxix). He takes Hays to be missing his point, which concerns “the distinctiveness of the particular exegetical procedures and practices that Paul uses in spelling out . . . his theological approach” (xxxvi). It is these—along with, e.g., methods such as “dreams and visions, ecstatic prophecies, the fleece of a sheep, necromancy” as well as casting lots—which Longenecker deems “culturally conditioned and not normative for believers today.” He thus wants to distinguish “between (1) normative theological and ethical principles and (2) culturally conditioned methods and practices used in the support and expression of those principles,” a distinction he takes to be commonly accepted by Christian churches that are not restorationist or primitivist in bent (xxxvii). In this way, he agrees with Hays about the normativity of the New Testament’s interpretations of Scripture, but disagrees with him about their interpretive methods, judging these to be “culturally conditioned” (xxxviii). On the contrary, it is not “my business to try to reproduce the exegetical procedures and practices of the New Testament writers, particularly when they engage in . . . ‘midrash,’ ‘pesher,’ or ‘allegorical’ exegesis,” which practices “often represent a culturally specific method or reflect a revelational stance, or both.” (He does not specify what “a revelational stance” is.) Finally, Longenecker does not share Hays’s conviction about Christian hermeneutical boldness, which would seek to follow Paul’s example; similar attempts have been made in the church’s history, but “usually with disastrous results.” The proper contemporary task, for ordinary believers and Christian scholars alike, is to recontextualize the content of the apostolic proclamation today, seeking “appropriate ways and means in our day for declaring and working out the same message of good news in Christ that they proclaimed” (xxxix).

There are a number of problems here. First, regarding imitation of apostolic exegesis, it would be helpful to make a distinction between formal, material, and methodological. Longenecker is right to say that we may not need or want to imitate the apostles in the specific methods of their exegesis (though, even here, the emphasis is on “may not”). But this does not answer the larger question. Hays’s proposal is at both the formal and the material level: formally, we should read the Old Testament (with the apostles) in the light of the events (and texts) of the New; materially, we should read the Old Testament (with the apostles) as in fact prefiguring, mysteriously, the gospel of the crucified and risen Messiah and of his body, the church. In doing so, Hays suggests, we will have read well, and will be well served in our exegetical judgments.

Second, Longenecker uses the modifier “culturally conditioned” regarding apostolic practice as if it is doing a good deal more work than it is. As he allows, our own methods are equally culturally conditioned. Well, then we need reasons—good reasons—why our own exegesis definitely should not conform, or even loosely imitate, that of the apostles. Longenecker seems to think that we are a long ways away from apostolic practice. But we stand at the end of a tradition that reaches back to the New Testament, and a good deal of Christian interpretation since then has taken its lead from apostolic example; moreover, scholarly practice is not a useful indicator for the breadth of Christian exegetical habits. On the ground, churches around the world inculcate and encourage habits of reading that follow the New Testament’s example quite closely. If Longenecker’s only criterion is cultural conditionedness, does he have any objection to this? How could he?

Relatedly, third, beyond the unobjectionable fact that apostolic practice can be and has been adopted, does Longenecker have good reasons to object to Hays suggesting that apostolic practice ought to be adopted? It is not as if we are locked into the cage of our cultural context, unable to make decisions about what we should or should not do. Hays proposes we look to Paul and, in our own time and place, follow his practice in his time and place. What arguments does Longenecker have to offer against this, other than the (universally admitted and materially irrelevant) observation that the practice in question is culturally conditioned?

Fourth and finally, Longenecker veers too close to positing something like “timeless truths” in the New Testament texts, while simultaneously (and oddly) undercutting the possibility of making cross-cultural judgments about common corporate practices like reading. On the one hand, he thinks the apostles deliver to us the true and reliable gospel message, albeit arrived at by methods that are culturally conditioned and, for that reason, not to be imitated by us. On the other hand, his picture presents the methods of “then and there” as if they reside across a great unbridgeable chasm, beyond recovery or the desire for recovery; whereas the methods of “here and now” are similarly cordoned off from criticism coming, as it were, in the reverse direction—that is, criticism by the standards of the Bible’s own exegetical practices. This picture is problematic both at a historical and a theological level. Surely different eras and cultures can comment on and evaluate others, provided they do so with respect and charity. In short: Can Christians really envisage the church’s history in such a way that whole epochs are sealed off from interrogation and/or imitation, by virtue of no other fact than that they are another time and place than our own?

"Speak a language, speak a people": Willie Jennings on Pentecost

"God has, however, now revealed a mighty hand and an outstretched arm reaching deeply into the lives of the Son's co-travelers and pressed them along a new road into the places God seeks to be fully known. This is first a miracle of hearing. . . .

"The miracles are not merely in ears. They are also in mouths and in bodies. God, like a lead dancer, is taking hold of her partners, drawing them close and saying, 'Step this way and now this direction.' The gesture of speaking another language is born not of the desire of the disciples but of God, and it signifies all that is essential to learning a language. It bears repeating: this is not what the disciples imagined or hoped would manifest the power of the Holy Spirit. To learn a language requires submission to a people. Even if in the person of a single teacher, the learner must submit to that single voice, learning what the words mean as they are bound to events, songs, sayings, jokes, everyday practices, habits of mind and body, all within a land and the journey of a people. Anyone who has learned a language other than their native tongues knows how humbling learning can actually be. An adult in the slow and often arduous efforts of pronunciation may be reduced to a child, and a child at home in that language may become the teacher of an adult. There comes a crucial moment in the learning of any language, if one wishes to reach fluency, that enunciation requirements and repetition must give way to sheer wanting. Some people learn a language out of gut-wrenching determination born of necessity. Most, however, who enter a lifetime of fluency, do so because at some point in time they learn to love it.

"They fall in love with the sounds. The language sounds beautiful to them. And if that love is complete, they fall in love with its original signifiers. They come to love the people—the food, the faces, the plans, the practices, the songs, the poetry, the happiness, the sadness, the ambiguity, the truth—and they love the place, that is, the circled earth those people call their land, their landscapes, their home. Speak a language, speak a people. God speaks people, fluently. And God, with all the urgency that is with the Holy Spirit, wants the disciples of his only begotten Son to speak fluently too. This is the beginning of a revolution that the Spirit performs. Like an artist drawing on all her talent to express a new way to live, God gestures the deepest joining possible, one flesh with God, and desire made one with the Holy One.

"Yet here we can begin to see even more clearly the ancient challenge and the modern problem. The ancient challenge is a God who is way ahead of us and is calling us to catch up. The modern problem is born of the colonial enterprise where language play and use entered its most demonic displays. Imagine peoples in many places, in many conquered sites, in many tongues all being told that their languages are secondary, tertiary, and inferior to the supreme languages of the enlightened peoples. Make way for Latin, French, German, Dutch, Spanish, and English. These are the languages God speaks. These are the scholarly languages of the transcending intellect and the holy mind. Imagine centuries of submission and internalized hatred of mother tongues and in the quiet spaces of many villages, many homes, women, men, and children practicing these new enlightened languages not by choice but by force. Imagine peoples largely from this new Western world learning native languages not out of love, but as utility for domination. Imagine mastering native languages in order to master people, making oneself their master and making them slaves. Now imagine Christianity deeply implicated in all this, in many cases riding high on the winds of this linguistic imperialism, a different sounding wind. Christianity was ripe for this tragic collaboration with colonialism because it had learned before the colonial moment began to separate a language from a people. It had learned to value, cherish, and even love the language of Jewish people found in Scripture—but hate Jewish people.

"Thankfully this is not the only story of Christianity in the colonial modern. There are also the quiet stories of some translators, and the peculiar few missionaries who from time to time and place to place showed something different. They joined. They, with or without 'natural language skill,' sought love and found it in another voice, another speech, another way of life. They showed something in their utter helplessness in the face of difference: they were there in a new land to be changed, not just change people into believers. they were there not just to make conquered Christians but truly and deeply make themselves Christian in a new space that would mean that their names would be changed. They would become the sound of another people, speaking the wonderful works of God. However these stories remain hidden in large measure from the history of Christianity that we know so well, which means we often know so little of Christianity."

—Willie Jame Jennings, Acts: A Theological Commentary on the Bible (2017), 28-31 (my emphasis). This work is extraordinary for its beauty, creativity, depth, and wonder; it reads as a series of kerygmatic riffs, ruminations, and exhortations on the words of Acts as they encounter the church today. Not every commentary can or should look like this, but it is nonetheless scriptural commentary at its best and most enriching.

A Question for Richard Hays: Metalepsis in The Leftovers

So Jamison hands Garvey a marked passage, and Garvey reads:

The passage is Job 23:8-17 (NIV). The scene is probably the most affecting—and least typical (i.e., not Psalm 23 or Genesis 1 or a Gospel)—reading of Scripture I've ever witnessed on screen.

And it got me thinking about Richard Hays. Specifically, it got me thinking about his books Echoes of Scripture in the Letters of Paul (1989) and Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels (2016). In those books Hays uses a literary device called "metalepsis" to uncover or identify allusions to passages of the Old Testament beyond what is explicitly cited in the New Testament. The idea is that, say, if a small portion of a Psalm is excerpted in a Gospel or Epistle, the author is thereby calling forth the whole Psalm itself, and that attentive readers of Scripture should pay attention to these intertextual echoes, which will expand the possible range of a text's meaning beyond what it may seem to be saying on the surface. So that, for example, when Jesus quotes Psalm 22 on the cross, those who know that that Psalm ends in deliverance, vindication, and praise will interpret the cry of dereliction differently than those who understand it as the despairing separation of the Son from the Father.

At last year's meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, there was a session devoted to Hays's latest book. When it came time for questions, I raised my hand. I asked whether his argument rested on authorial intention, that is, whether, if we could know for certain that the Evangelists did not intend any or most of the metaleptic allusions Hays draws attention to in his book, that would nullify his case; or whether we, as Christian readers of Holy Scripture, are authorized to read the New Testament in light of the Old in ways its authors never intended. Hays assumed I hadn't read the book and that I was asking on behalf of authorial intention (i.e., he and Sarah Coakley both treated me a bit like a hostile witness, when I was anything but), but he answered the question directly, and in my view rightly: Yes, the metaleptic readings stand, apart from historical claims about authorial intention. Whatever Mark may have meant by the quotation of Psalm 22, we aren't limited by that intention, knowing what we know, which includes the entirety of the Psalm.

So back to The Leftovers. May we—should we—apply the hermeneutic principle of metalepsis to this scene's use of Scripture (and scenes like it)? What would happen if we did?

When I first watched the episode, I mistakenly thought that the famous passage from Job 19—"I know that my redeemer lives..."—followed the words cited on screen, which is what triggered the idea about metalepsis. In other words, if Job 23 were followed by words of bold hope in God, should that inform how we interpret the scene and its use of the quotation? Even granted my error, there is the wider context of the book of Job, and in particular the conclusion, in which God speaks from the storm, and Job is reduced to silence before God's absolutely unanswerable omnipotence—or, better put, his sheer divinity, his incomparable and singular God-ness. Might we interpret this scene, Garvey's story in season 1, and the whole series in light of this wider context?

It seems to me that we can, and should. But then, I'm only halfway through season 2. Job comes up again in episode 5 of that season, when Jamison is asked what his favorite book of the Bible is, and gives some trivia about Job's wife. Which suggests to me that perhaps Damon Lindelof and his fellow writers may be wise to the wider context and meaning of Job, in which case we viewers may not have to interpret against authorial intention at all.

That's a bit less fun, though it increases my respect for the show and the artists behind it. In any case, I'll let you know what I think once I finish.

David Bentley Hart on contemporary versus premodern allegorization

—David Bentley Hart, "Ad Litteram" (now collected in A Splendid Wickedness and Other Essays, 274-277). This is absolutely correct, and the entire (brief) essay should be required reading for biblical scholars, whether disposed to historical criticism or any other scholarly hermeneutic.