Resident Theologian

About the Blog

Scorsese

Brief thoughts on gratuitous content in Martin Scorsese’s films.

I was impressed with Mr. Scorsese, the new five-part documentary (or “film portrait”) about Martin Scorsese on Apple TV+, directed by Rebecca Miller. I’ve never been a true devotee of Scorsese, but I’ve always appreciated his work and usually defended him from detractors. Over the years I’ve seen most of his films and all the major ones. (I’ve not seen, e.g., Boxcar Bertha or Cape Fear. I keep trying to get Kundun on DVD via ILL, but no luck so far.) Even those who don’t prefer his work can admit his status as a great American artist with a recognizable moral, political, religious, and stylistic perspective.

That’s a boilerplate paragraph, but I say it to say this: Something in the documentary nagged at me. Miller allowed herself a moderate degree of criticism, but less of Scorsese’s art than of his life. Regarding Scorsese’s actual critics, the lesson we learn from the entire film and from Scorsese himself is that, at the end of the day, they are haters or skeptics or simply confused; they fail to grasp the significance and rationale, in particular, of the gratuitous violence and sex in his films.

There is, regrettably, not a trace of aesthetic self-criticism in Scorsese the man, no Augustinian retractationes. He never says, “I went too far,” or, “You know, they had a point about this one.” Every decision about graphic content is justified because … well, why?

Because, so far as I can tell, “that’s what the world is like” or “that’s what American society is like.” Okay. But that doesn’t tell me whether rubbing our faces in it—while appearing to glorify it in the process—is morally or aesthetically warranted. Such a comment is the beginning of a conversation, not its end.

You don’t have to be a “trash in, trash out” puritanical simpleton (that’s me, to be clear) to draw moral and aesthetic distinctions between, for example, the depictions of sex and violence in Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, on one hand, and those in Casino and Wolf of Wall Street on the other. For me, Goodfellas resides somewhere in the middle. I marvel at the achievement while unable, in my heart, to keep myself from applying Truffaut’s rule about war films to mafia films, with Goodfellas even more than The Godfather the Platonic exemplification of the rule’s almost universal truth.

I just wish that someone would put this question to Scorsese himself, and that he would take it more seriously than he does here.

I’m in CT on the conquest

I’m in Christianity Today with a review of Charlie Trimm’s new book, The Destruction of the Canaanites: God, Genocide, and Biblical Interpretation.

I’m in Christianity Today with a review of Charlie Trimm’s new book, The Destruction of the Canaanites: God, Genocide, and Biblical Interpretation. Here’s how it opens:

There is a problem with the Old Testament. At a key juncture in salvation history, the God of Abraham commandeers one nation in order to destroy another. The aggressor nation attacks the second nation because God has judged the latter guilty. The aggressor is merciless, sparing neither women nor children, expelling the inhabitants from their land, and destroying sacred sites and symbols of religious practice—in effect, wiping them off the map. And, according to the Hebrew scriptures, all this happened by the terrible will of the sovereign Lord of Hosts.

It is a harrowing moment in the history of God’s people. But I am not referring to the conquest of Canaan by the tribes of Israel. I am referring to the assault on the northern kingdom of Israel by the Assyrians (a little over 700 years before the birth of Jesus) and the campaign against the southern kingdom, especially the city of Jerusalem and its temple, by the Babylonians about 130 years later.

Click here to keep reading. The book is excellent and I hope pastors and professors use it going forward. I also hope readers understand, once they finish the essay, that the opening line of the review is ironic.

On “anti" films that succeed, and why

More than one friend has pointed out an exception or addendum to my last post on "anti" films, which makes the claim that no "anti" films are successful on their own terms, for they ineluctably glorify the very thing they are wanting to hold up for critique: war, violence, misogyny, wealth, whatever.

More than one friend has pointed out an exception or addendum to my last post on "anti" films, which makes the claim that no "anti" films are successful on their own terms, for they ineluctably glorify the very thing they are wanting to hold up for critique: war, violence, misogyny, wealth, whatever.

The exception is this: There are successful "anti" films—meaning dramatic-narrative films, not documentaries—whose subject matter is intrinsically negative, and not ambiguous or plausibly attractive. Consider severe poverty, drug addiction, or profound depression. Though it is possible to make any of these a fetish, or to implicate the audience as a voyeur in relation to them, there is nothing appealing about being depressed, addicted, or impoverished, and so the effect of the cinematic form does nothing to make them appealing: for the form magnifies, and here there is nothing positive to magnify, only suffering or lack.

So, for example, The Florida Project and Requiem for a Dream and Melancholia are successful on their own terms; my critique of "anti" films does not apply to them.

But note well a few relevant features that distinguish these kinds of movies.

First, no one would mistake such films for celebrations of poverty, drug abuse, or depression. But that isn't because they're overly didactic; nor is it because other "anti" films aren't clear about their perspective. It's because no one could plausibly celebrate such things. But people do mistake films about cowboys, soldiers, assassins, vigilantes, gangsters, womanizers, adulterers, and hedge fund managers(!) as celebrations of them and their actions.

Second, this clear distinction helps us to see that films "against" poverty et al are not really "anti" films at all. Requiem is not "anti-hard drugs": it is about people caught up in drug abuse. It's not a D.A.R.E. ad for middle schoolers—though, as many have said, it certainly can have that effect. In that film Aranofsky glamorizes nothing about hard drugs or the consequences of being addicted to them. But that is more a critique of the way most films ordinarily bypass such consequences and focus on superficial appurtenances of the rich and famous, including the high of drugs but little more.

Third, this clarification helps to specify what I mean by "anti" films. I don't mean any film that features a negative subject matter. I mean a film whose narrative and thematic modus operandi is meant to be subversive. "Anti" films take a topic or figure that the surrounding culture celebrates, enjoys, or prefers left unexamined and subjects it to just that undesired examination. It deconstructs the cowboy and the general and the captain of industry. Or it does the same to the purported underbelly of society, giving sustained and sympathetic attention to the Italian mafia or drug-runners or pimps or what have you. In the first case, the lingering, affectionate gaze of the camera cannot but draw viewers into the life of the heretofore iconic figure, deepening instead of complicating their prior love. In the second, the camera's gaze does the same for previously misunderstood or despised figures. Michael Corleone and Tony Montana and Tommy DeVito become memorialized and adored through repeated dialogue, scenes, posters, and GIFs. Who could resist the charms of such men?

Fourth, the foregoing raises the question: Why are bad things like crime and violence and illicit sex plausibly "attractive" to filmmakers and audiences in a way that other bad things are not? I think the answer lies, on the one hand, with the visual nature of the medium: sex and violence, not to mention the excitement and/or luxury bound up with the life of organized crime, are visual and visually thrilling actions; in the hands of gifted directors, their rendering in film is often gorgeous and alluring to behold. Bodies in motion, kinetic choreography, beautiful people doing physically demanding or intriguing or seductive deeds: the camera was made for such things. Depression and deprivation? Not so much. (A reminder that film is not a medium of interiority; psychology is for print.)

On the other hand, the perennial topics of "anti" films are, as I said in my first post, not wholly bad things. War, needless to say, is a deeply complex phenomenon: just causes and wicked intentions, wise leaders and foolish generals, acts of heroism and indiscriminate killing, remarkable discipline and wanton destruction. War is a force that gives us meaning for a reason. But sex and westerns and extravagant wealth and even organized crime are similarly ambivalent, which is to say, they contain good and bad; or put differently, what is bad in them is a distortion of what is good. The Godfather is a classic for many reasons, but a principal one is its recognizable depiction of an institution in which we all share: family.

One friend observed that, perhaps, films cannot finally succeed in subverting vices of excess, but they can succeed in negative portrayals of vices of privation. I'll have to continue to ruminate on that, though it may be true. Note again, however, the comment above: vices of privation are not generally celebrated, admired, or envied; there is no temptation to be seduced by homelessness, nor is the medium of film prone to glorify it. Which means there is nothing subversive, formally speaking, about depicting homelessness as a bad thing that no one should desire and everyone should seek to alleviate. Whereas an "anti" film, at least in my understanding of it, is subversive by definition.

Fifth, another friend remarked that the best anti-war films are not about war at all: the most persuasive case against a vice is a faithful yet artful portrait of virtue. Broadly speaking, I think that is true. Of Gods and Men and A Hidden Life are "anti-war" films whose cameras do not linger on the battlefield or set the audience inside the tents and offices of field generals and masters of war. Arrival is a "pro-life" film that has nothing to do with abortion. So on and so forth. I take this to be a complimentary point, inasmuch as it confirms the difficulty (impossibility?) of cinematic "anti" films, according to my definition, and calls to mind other mediums that can succeed as subversive art: literature, poetry, music, photography, etc. I think the phenomenon I am discussing, in other words, while not limited to film, is unique in the range and style of its expression—or restriction—in film.

A simple way to put the matter: no other art form is so disposed to the pornographic as film is. The medium by its nature wants you to like, to love, to be awoken and shaken and shocked and moved by what you see. It longs to titillate. That is its special power, and therefore its special danger. That doesn't make it all bad. Film is a great art form, and individual films ought to be considered the way we do any discrete cultural artifact. But it helps to explain why self-consciously "subversive" films continually fail to achieve their aims, inexorably magnifying, glamorizing, and glorifying that which they seek to hold up to a critical eye. And that is why truly subversive literary art so rarely translates to the screen; why, for example, Cormac McCarthy's "anti-western" Blood Meridian is so regularly called "unfilmable." What that novel induces in its readers, not in spite of but precisely in virtue of its brilliance, is nothing so much as revulsion. One does not "like" or identify with the Kid or the Judge or their fellows. One does not wish one were there. One is sickened, overwhelmed with the sheer godforsaken evil and suffering on display. No "cowboys and Indians" cosplay here. Just violence, madness, and death.

Can cinema produce an anti-western along the same lines? One that features cowboys and gorgeous vistas and heart-pounding action and violence? Filmmakers have tried, including worthy efforts by Clint Eastwood, Tommy Lee Jones, and Kelly Reichardt. I'd say the verdict is still out. But even if their are exceptions, the rule stands.

No such thing as an anti-war film, or anti-anything at all

There is no such thing as an anti-war film, François Truffaut is reported to have said. In a manner of speaking, there is no such thing as an anti-anything film, at least so long as the subject in question is depicted visually.

There is no such thing as an anti-war film, François Truffaut is reported to have said. In a manner of speaking, there is no such thing as an anti-anything film, at least so long as the subject in question is depicted visually.

The reason is simple. The medium of film makes whatever is on screen appealing to look at—more than that, to sink into, to be seduced by, to be drawn into. Moving images lull the mind and woo the heart.

Moreover, anything that is worth opposing in a film contains some element of goodness or truth or beauty. The wager or argument of the filmmaker is not that the subject matter is wholly evil; rather, it is that it is something worthwhile that has been corrupted, distorted, or disordered: by excess, by wicked motives, by tragic consequences. Which means that whatever is depicted in the film is not Evil Writ Large, Only Now On Screen. It is something lovely or valuable—something ordinary people "fall for" in the real world—except portrayed in such a way as to try to show the harm or problems attending it.

Unfortunately, the form of film itself works against the purposes of an "anti film," since the nature of the form habituates an audience to identify with and even love what is on screen. Why? First, because motion pictures are in motion, that is, they take time. Minute 30 is different than minute 90. Even if minute 90 "makes the point" (whether subtly or didactically), minutes 1 through 89 might embody the opposite point, and perhaps far more powerfully.

Second, cinematic form is usually narrative in character. That means protagonists and plot. That means point of view, perspective. That means viewers inevitably side with, line up with, a particular perspective or protagonist. And when that happens, sympathies soften whatever critique the filmmaker wants to communicate; the "bad fan" effect generates a shared instinct to cheer on the lead, however Illustratively Bad or even an Unqualified Antihero he may be. If only Skyler wouldn't get in Walter's way, you know?

Third, the temporal and narrative shape of film means that endings mean everything and nothing. Everything, because like all stories they bring to a head and give retroactive meaning to all that came before. Nothing, because what many people remember most is the experience of the journey getting there. And if the journey is 99% revelry in Said Bad Thing, even if the final 1% is denunciation thereof, what people will remember and continue returning for is the 99%. And that's just not something you can control, no matter how blunt you're willing to be in the film's flashing-neon messaging.

That, in short, is why there are no "anti" films, only failed attempts at them.

No anti-war films: only films that glorify the spectacle and heroes of warfare.

No anti-gangster films: only films that glorify the thrills of organized crime.

No anti-luxury films: only films that glorify the egregious excesses of the 1%.

No anti-western films: only films that glorify the cowboy, the vigilante, and lawless violence.

No anti-ultraviolence films: only films that glorify the wild anarchy of the uncontrolled and truly free.

No anti-misogynist films: only films that glorify the untamed libido and undomesticated talk of the charming but immature adolescent or bachelor.

And finally, no films subversive of the exploitation and sexualization of young girls: only films that glorify the same. To depict that evil, in this medium, in a way that captures faithfully the essence of the evil, is little more than reproducing the evil by other means, in another form. However artful, however sophisticated, however well-intended, it is bound for failure—a failure, I hasten to add, for which the filmmakers in question are entirely culpable.

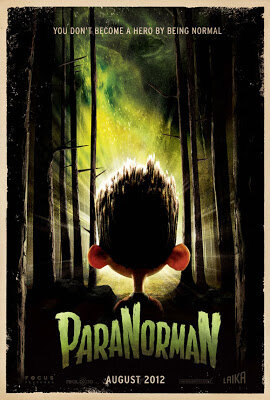

"Nobody's stronger than forgiveness": breaking the cycle of fear and violence in ParaNorman

Did This Ever Happen to You

A marble-colored cloud

engulfed the sun and stalled,

a skinny squirrel limped toward me

as I crossed the empty park

and froze, the last

or next to last

fall leaf fell but before it touched

the earth, with shocking clarity

I heard my mother’s voice

pronounce my name. And in an instant I passed

beyond sorrow and terror, and was carried up

into the imageless

bright darkness

I came from

and am. Nobody’s

stronger than forgiveness.

—Franz Wright, God's Silence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), p. 22

- - - - - - -

(Spoilers to follow.)

(Spoilers to follow.)Written by Chris Butler and co-directed by Butler with Sam Fell, ParaNorman seems at the outset to be a rather straightforward "kids' movie" within a certain recognizable genre. It quickly becomes evident, however, that the story being told is not as ordinary as one might expect.

Norman Babcock is an outcast at home and at school, and for a simple reason: he sees the ghosts of dead people, regularly talks to them, and doesn't hide the fact. His dad thinks he's a weirdo, his mom isn't sure how to relate to him, and his sister can't stand him. At school people part the way for him and whisper as he trudges along; he keeps a wet rag in his locker to wipe off the word "FREAK" scrawled anew each day on his locker door. A bully, Alvin -- a cinematic Moe from Calvin and Hobbes if there ever was one -- makes his life miserable. The one gleam of light in this daily darkness is the friendly overtures of Neil, a similarly bullied "fat kid" who doesn't let it get him down. When Norman says he prefers to be alone, Neil agrees: He just wants to be "alone together."

Norman lives in Blithe Hollow, a town founded by Puritans and known for its trial and execution of a purported witch nearly 300 years ago -- in fact, tonight is the eve of that anniversary. The legend is that at her sentencing, the witch (imagined as an ugly old green-nosed hag) cursed her accusers, and that all seven of them (the judge and the jury) went to their graves bearing this curse.

A kooky uncle who can also see and speak to ghosts finds Norman and (just before dying himself) tells Norman it's up to him to keep the curse at bay, that very evening before midnight. Unfortunately, before he can figure out quite how to follow his uncle's instructions, the seven Puritan accusers rise from the dead as zombies and start pursuing Norman (albeit very slowly) and whoever is with him. As Norman tries to escape and figure out how to kill or at least send them back to the grave, he picks up a ragtag crew: Alvin, Neil, his looks-obsessed sister Courtney, and Neil's beefy but dim-witted brother Mitch. Unsurprisingly, once the town discovers the dead walk the streets, they form a mob (armed with pitchforks, shotguns, and bowling balls) and chase both Norman's crew and the zombies to city hall, where in a frenzy they seek to kill not only the zombies but Norman himself, too, for bringing this terror upon them.

An unexpected series of events, however, reveals the true nature of what is going on. The undead Puritans don't want to kill Norman or anyone else: they want their curse undone. They want peace in death, not more death for others. Norman sees the reality of what happened three centuries before: the person sentenced by the court to death for witchcraft wasn't a green-nosed hag, but a child like him -- a little girl who happened to be playing with fire (both literally and figuratively), and found out by the wrong people. Caught and punished unjustly by these townspeople so blindly fearful of her, she in her anger and fear of them in turn cursed them to their graves, so that they would never know the peace she herself was robbed of.

Now Norman sees, as do his sister and and oddball friends: The curse isn't limited to the Puritans, nor are its consequences merely to be trapped in a living death. No, the curse is on the entire town, for the very cycle of fear of the unknown and the turn to violence has engulfed the mob standing outside city hall, trying to burn the place down. And it won't end with the death of either the zombies or Norman himself. Something else, something new, has to happen.

So Norman leads his crew and the zombies outside to meet the mob where they stand. After stilling their frenzy, he tells them the story he just learned. Following Norman's lead, his unlikely fellows -- a resentful sister, an overweight outcast, a former bully, and a (later revealed as gay!) beefcake -- bear witness to the crowd that what Norman has told them is true, and further appeal to them to let go of their fear. For in fact, they have nothing to fear; the zombies don't want to hurt them, they only want to find the means to pass on peacefully.

As the truth dawns on the mob, the camera pans across their feet, as each and all drop their weapons: a club, a pitchfork, a shotgun, a bowling ball. "At this, those who heard began to go away one at a time, the older ones first . . ." The town lays down their instruments of violence, with eyes opened by the truth, freed from their bondage to fear of the other as threat.

But this isn't the end. The ghost of the witch, now enraged, begins to wreak havoc on the town. So Norman's parents take him, his sister, and the zombie Puritan judge to the witch's unmarked grave. There Norman engages in a climactic encounter with the witch's ghost, not with force or deception, but just as before with the crowd: with a true story. In fact, the way in which previous "ghost-seers" like him had kept the witch at bay was by reading a fairy tale to her, that is, they read her a nice bedtime story to palliate her righteous anger and get her to "sleep" for a little while longer.

But Norman knows better. That only puts a bandage on the wound, it won't heal the town's history or the witch's hurt. So he tells her a different story: her own. Though she tries to stop him in every way she can (with fantastic and terrifying powers), he re-narrates her life, without blushing or overlooking the hurt and the wrong and the injustice of it. But finally -- with what feels like his last ounce of energy -- finally he helps her to see. And she sees not only her tragic situation, but also the tragic nature of her accusers: they weren't pure evil or all powerful; they were afraid of her, hard as it is to believe. And though what they did was unspeakably wrong, to inflect on them and thus on the town what they inflicted on her is only to become a monster like them, when she could choose otherwise and free the town of its curse.

Reverting for a moment to her living form, Aggie -- for that was her name -- tells Norman of her sadness, how she misses her mom, how she was only playing with fire. Norman comforts her, but urges her to let go and be at peace, and to do so she has to forgive. Aggie asks Norman: What is the ending to the story he's telling? Norman replies that that's up to her.

After considering, the witch opts for peace; Aggie forgives those who knew not what they did, and so gives up her spirit, passing on peacefully to be with her beloved mother. The zombies, too, pass on, but not before changing from undead to dead, that is, from zombies to ghosts: they go on as themselves, the curse undone, rather than into one more mode of accursed existence.

Norman walks through the rubble of the town, listening to his neighbors' conversations. A former outcast, he surveys those once divided from him and from one another now chatting and listening and laughing with one another. Returning home, he plops in front of the TV for his usual routine of horror flicks. Typically alone with his movies and the ghost of his grandmother, his family joins him, Norman's dad even going out of his way to acknowledge the previously doubted presence of his deceased mother.

Whether in his town, with his new friends, or here at home with his family, Norman isn't alone anymore. The dividing walls have come down; the cycles of fear and violence have been broken; the weirdos and the bullies have embraced; the town knows its history, broken and redeemed. No, neither Norman nor his town nor his family is alone; no longer are they isolated from one another.

In Neil's words, they're alone together.