Resident Theologian

About the Blog

Update on my next two books

An update on my next two books, both due next year. The first is called The Church: A Guide to the People of God; the second is called Letters to a Future Saint: A Catechism for Believers on the Way.

My first two books, The Doctrine of Scripture and The Church’s Book, were published in August 2021 and April 2022, respectively, just eight months apart. Now it’s looking like the next two will be published in a similarly short span.

Book #3 is titled The Church: A Guide to the People of God. It’s in the Christian Essentials series published by Lexham Press; it’ll be the sixth of nine total volumes. The first five cover the Apostles’ Creed (Ben Myers), the Ten Commandments (Peter Leithart), the Lord’s Prayer (Wesley Hill), baptism (Peter Leithart), and the Bible (John Kleinig). The remaining three address the liturgy, the Eucharist, and the forgiveness of sins. The whole series will eventually form a trilogy of trilogies: Creed–Prayer–Decalogue; Church–Scripture–Liturgy; Baptism–Eucharist–Absolution.

I worked out the final version of the manuscript with the wonderful Todd Hains last April, and sometime in the next few weeks I’ll receive and approve the copy-edited proofs before they’re handed on to be typeset. We’re expecting the book to come out next spring (if I’m guessing, let’s say March 25, 2024—the book begins with the Annunciation, after all).

Book #4 is titled Letters to a Future Saint: A Catechism for Believers on the Way. I finished a draft this past May, sat on it over the summer, got feedback from readers, and made final revisions this month. Two days ago I emailed it to James Ernest at Eerdmans (James is the reason I wrote this book in the first place). Obviously he and the other Eerdmans editors have to like the book and formally approve it. On the assumption they will and do, with however many suggested changes, the book should come out late fall next year (let’s say October 1, 2024, since Saint Thérèse is a kind of patroness for the book—though to be honest, my guess would be mid-November, just before AAR/SBL/Thanksgiving/Advent).

Both books are meant for lay readers of all ages. I was just telling someone yesterday that writing for a popular audience is both harder and more fun to write than anything else. It requires intense discipline not to indulge all your bad habits: not to say everything; not to use jargon; not to presuppose background knowledge, but also not to overwhelm—all while holding the reader’s attention with shorter sentences and paragraphs and chapters, without the crutch of ten trillion ego-padding footnotes.

Each book is an outgrowth of my time in the classroom here at ACU. I have taught the same upper-level course on ecclesiology every fall semester since 2017. The Church is simply that class rendered in print. My special hope is that it reaches readers who love Christ but don’t understand why His body and bride matters; or who “get” the Church but don’t “get” Abraham and Moses and Israel. Let me be the one to tell them!

Letters to a Future Saint is meant for anyone old enough to read it—from high schoolers to senior citizens—but the primary audience I have in mind is the students I teach every day. On one hand, they mostly don’t read books; they largely come from Bible Belt contexts; they’re typically non-denom evangelicals; they’re baptized but uncatechized. On the other hand, they’re earnest, hungry, and eager to learn; they know Christ and want to know Him more; they’re willing to labor and struggle to get there. In other words, they’re young people in the orbit of the Church but in need of meat, not milk. I want to catechize them. I want my book to be a tool in the hands of professors, pastors, parents, grandparents, mentors, volunteers, youth groups, study groups, Bible studies, Christian colleges, and Christian study centers. I want older believers to say, “This is a book that will draw you into the depths of the faith—a book you can understand, a book you’ll enjoy, yet also a book that will show you why living and dying for Christ makes sense.” That’s a high goal, and I’ve surely failed to meet it in countless ways, but it’s my hope nonetheless.

In both books I have sought to be ecumenical without being generic; I have tried, that is, to be at once biblical, creedal, evangelical, and catholic. My Catholic friends observed how saturated the manuscripts are with the Old Testament; my evangelical friends noted how capital-O Orthodox they seem; my academic friends were struck by the devotional and even pious tone. Lord willing, these add up to a holistic whole and not a false eclecticism. I want readers of all backgrounds to find profit in what I’ve written. And even when something is foreign or initially off-putting, I long for it not to lead them to put down the book, but to keep reading to learn more.

Now to wait. Next year feels a long ways off. What am I supposed to do with my time when I’m not obsessively breathlessly writing rewriting revising two books simultaneously? I guess we’ll see.

The Liberating Arts is out today!

It’s pub day for The Liberating Arts!

More than three years ago I joined a team of scholars on a grant-funded project called “The Liberating Arts.” We created a website and conducted dozens of video interviews with fellow writers, academics, educators, and intellectuals about the present and future of the liberal arts. The interviews are also available in podcast form.

Today is one more fruit of that long-standing project: a book! It’s called The Liberating Arts: Why We Need Liberal Arts Education. Published by Plough, it was edited by our fearless leaders Jeff Bilbro, Jessica Hooten Wilson, and David Henreckson. And it’s out today. Go buy it directly from Plough, or on Bookshop, or on the Bezos Site, or wherever else you purchase books. Request another copy for your library! And suggest it to your dean or chair or provost or study center as a common read! You won’t regret it.

What is the book, you ask? See below for a description. Let me tell you first whose essays are found between its covers (besides the editors’ and my own): Emily Auerbach, Nathan Beacom, Joseph Clair, Margarita Mooney Clayton, Lydia Dugdale, Don Eben, Becky L. Eggimann, Rachel Griffis, Zena Hitz, David Hsu, L. Gregory Jones, Brandon McCoy, Peter Mommsen, Angel Adams Parham, Steve Prince, John Mark Reynolds, Erin Shaw, Anne Snyder, Sean Sword, Noah Toly, and Jonathan Tran. Those are names worth reading.

What about endorsements? Check out these:

At their best, the humanities are about discerning what kinds of lives we should be living. But humanities education is in crisis today, leaving many without resources to answer this most important question of our lives. The authors of this volume are able contenders for the noble cause of saving and improving the humanities. Read and be inspired! —Miroslav Volf, co-author, Life Worth Living

In this lucid and inspiring volume, a diverse group of thinkers dispel entrenched falsehoods about the irrelevance, injustice, or uselessness of the liberal arts and remind us that nothing is more fundamental to preparing citizens to live in a pluralistic society attempting to balance the values of justice, equality, and community. —Jon Baskin, editor, Harper’s and The Point

In this series of lively, absorbing, and accessible essays, the contributors invoke and dismantle all the chief objections to the study of the liberal arts. The result is a clarion call for an education that enables human and societal flourishing. Everyone concerned about the fate of learning today must read this book. —Eric Adler, author, The Battle of the Classics

In our era of massive social and technological upheaval, this book offers a robust examination of and an expansive vision for the liberal arts. As a scientist who believes that education should shape us for lives of reflection and action, I found the essays riveting, challenging, and inspiring. I picked it up and could not put it down. —Francis Su, author, Mathematics for Human Flourishing

The Liberating Arts is a transformative work. Opening with an acknowledgement of the sundry forces arrayed against liberal arts education today, this diverse collection of voices cultivates an expansive imagination for how the liberal arts can mend what is broken and orient us individually and collectively to what is good, true, and beautiful. —Kristin Kobes du Mez, author, Jesus and John Wayne

And here’s a snapshot of what we’re up to in the book…

*

Why would anyone study the liberal arts? It’s no secret that the liberal arts have fallen out of favor and are struggling to prove their relevance. The cost of college pushes students to majors and degrees with more obvious career outcomes.

A new cohort of educators isn’t taking this lying down. They realize they need to reimagine and rearticulate what a liberal arts education is for, and what it might look like in today’s world. In this book, they make an honest reckoning with the history and current state of the liberal arts.

You may have heard – or asked – some of these questions yourself:

Aren’t the liberal arts a waste of time? How will reading old books and discussing abstract ideas help us feed the hungry, liberate the oppressed and reverse climate change? Actually, we first need to understand what we mean by truth, the good life, and justice.

Aren’t the liberal arts racist? The “great books” are mostly by privileged dead white males. Despite these objections, for centuries the liberal arts have been a resource for those working for a better world. Here’s how we can benefit from ancient voices while expanding the conversation.

Aren’t the liberal arts liberal? Aren’t humanities professors mostly progressive ideologues who indoctrinate students? In fact, the liberal arts are an age-old tradition of moral formation, teaching people to think for themselves and learn from other perspectives.

Aren’t the liberal arts elitist? Hasn’t humanities education too often excluded poor people and minorities? While that has sometime been the case, these educators map out well-proven ways to include people of all social and educational backgrounds.

Aren’t the liberal arts a bad career investment? I really just want to get a well-paying job and not end up as an overeducated barista. The numbers – and the people hiring – tell a different story.

In this book, educators mount a vigorous defense of the humanist tradition, but also chart a path forward, building on their tradition’s strengths and addressing its failures. In each chapter, dispatches from innovators describe concrete ways this is being put into practice, showing that the liberal arts are not only viable today, but vital to our future.

*

P.S. There is a launch event in Manhattan next month. Join Roosevelt Montás, Zena Hitz, Jessica Hooten Wilson, and Jonathan Tran to celebrate The Liberating Arts on September 28 at The Grand Salon of the 3 West Club ⁄ New York. Sign up here.

I’m on Mere Fidelity

Did I say quit podcasts? I meant all of them except one.

Did I say quit podcasts? I meant all of them except one.

I’m on the latest episode of Mere Fidelity, talking about my book The Doctrine of Scripture and, well, the doctrine of Scripture. (Links: Google, Spotify, Apple, Soundcloud.) It was a pleasure to chat with Derek and Alastair and (surprise!) Timothy. Matt had to bail last minute. I can only assume he was nervous.

No joke, it was an honor to be on. For the last decade, I have lived by the mantra, “No podcasts before tenure.” I’ve turned down every invitation. In 2020–21 I participated in three podcasts as a member of The Liberating Arts, the first two as the interviewer (of Alan Noble and Jon Baskin, respectively) and the third as interviewee, speaking on behalf of the project (this was 11 months ago, but the podcast just posted this week, as it happens). In other words, this experience with Mere Fi was for all intents and purposes my first true podcast experience, in full and on the receiving end.

It was fun! I hope I didn’t flub too many answers. I tend to speak in winding paragraphs, not in discrete and manageable sentences. Besides, it’s hard to compete with Alastair’s erudition—and that accent!

Check it out. And the Patreon, where there’s a +1 segment. Thanks again to the Mere Fi crew. I give all of you dear readers a big glorious exception to go and listen to them. They’ve got the best theology pod around. What a gift to be included on the fun.

The Church’s Book is here!

My new book, The Church’s Book, is here! Order today.

It’s here!

Or if you want a snazzy wrap-around image of the whole front and back matter…

The book is ready for order anywhere books are sold: Amazon, Bookshop, Eerdmans, elsewhere. Some websites may say that the publication date is May 24, but it’s available to be shipped at this moment—folks I know who pre-ordered it have already received a copy or are getting theirs by mail in a matter of days. And the Kindle edition will be available Tuesday next week, the 26th.

Here’s the book description:

What role do varied understandings of the church play in the doctrine and interpretation of Scripture?

In The Church’s Book, Brad East explores recent accounts of the Bible and its exegesis in modern theology and traces the differences made by divergent, and sometimes opposed, theological accounts of the church. Surveying first the work of Karl Barth, then that of John Webster, Robert Jenson, and John Howard Yoder (following an excursus on interpreting Yoder’s work in light of his abuse), East delineates the distinct understandings of Scripture embedded in the different traditions that these notable scholars represent. In doing so, he offers new insight into the current impasse between Christians in their understandings of Scripture—one determined far less by hermeneutical approaches than by ecclesiological disagreements.

East’s study is especially significant amid the current prominence of the theological interpretation of Scripture, which broadly assumes that the Bible ought to be read in a way that foregrounds confessional convictions and interests. As East discusses in the introduction to his book, that approach to Scripture cannot be separated from questions of ecclesiology—in other words, how we interpret the Bible theologically is dependent upon the context in which we interpret it.

Here are the blurbs:

“How we understand the church determines how we understand Scripture. Brad East grounds this basic claim in a detailed examination of three key heirs of Barthian theology—Robert Jenson, John Webster, and John Howard Yoder. The corresponding threefold typology that results —church as deputy (catholic), church as beneficiary (reformed), and church as vanguard (believers’ church)—offers much more than a description of the ecclesial divides that undergird different views of Scripture. East also presents a sustained and well-argued defense of the catholic position: church precedes canon. At the same time, East’s respectful treatment of each of his theological discussion partners gives the reader a wealth of insight into the various positions. Future discussions about church and canon will turn to The Church’s Book for years to come.”

— Hans Boersma, Nashotah House Theological Seminary“Theologically informed, church-oriented ways of reading Scripture are given wonderfully sustained attention in Brad East’s new book. Focusing on Karl Barth and subsequent theologians influenced by him, East uncovers how differences in the theology of Scripture reflect differences in the understanding of church. Ecclesiology, East shows, has a major unacknowledged influence on remaining controversies among theologians interested in revitalizing theological approaches to Scripture. With this analysis in hand, East pushes the conversation forward, beyond current impasses and in directions that remedy deficiencies in the work of each of the theologians he discusses.”

— Kathryn Tanner, Yale Divinity School“In this clear and lively volume, Brad East provides acute close readings of three theologians—John Webster, Robert W. Jenson, and John Howard Yoder—who have all tied biblical interpretation to a doctrine of the church. Building on their work, he proposes his own take on how the church constitutes the social location of biblical interpretation. In both his analytical work and his constructive case, East makes a major contribution to theological reading of Scripture.”

— Darren Sarisky, Australian Catholic University“If previous generations of students and practitioners of a Protestant Christian doctrine of Holy Scripture looked to books by David Kelsey, Nicholas Wolterstorff, and Kevin Vanhoozer as touchstones, future ones will look back on this book by Brad East as another. But there is no ecclesially partisan polemic here. This book displays an ecumenical vision of Scripture—one acutely incisive in its criticism, minutely attentive in its exposition, and truly catholic and visionary in its constructive proposals. It has the potential to advance theological discussion among dogmaticians, historians of dogma, and guild biblical exegetes alike. It is a deeply insightful treatment of its theme that will shape scholarly—and, more insistently and inspiringly, ecclesial—discussion for many years to come.”

— Wesley Hill, Western Theological Seminary“In the past I’ve argued that determining the right relationship between God, Scripture, and hermeneutics comprises the right preliminary question for systematic theology: its ‘first theology.’ Brad East’s The Church’s Book has convinced me that ecclesiology too belongs in first theology. In weaving his cord of three strands (insights gleaned from a probing analysis of John Webster, Robert Jenson, and John Howard Yoder), East offers not a way out but a nevertheless welcome clarification of where the conflict of biblical interpretations really lies: divergent understandings of the church. This is an important interruption of and contribution to a longstanding conversation about theological prolegomena.”

— Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School“For some theologians, it is Scripture that must guide any theological description of the church. For others, the church’s doctrines are normative for interpreting Scripture. Consequently, theologians have long tended to talk past one another. With unusual brilliance, clarity, and depth, Brad East has resolved this aporia by arguing that the locus of authority lay originally within the people of God, and thus prior to the development of both doctrine and Scripture. And so it is we, the people of God, who are prior, and who undergird both, and thereby offer the possibility of rapprochement on that basis. East’s proposal is convincing, fresh, and original: a genuinely new treatment that clarifies the real issues and may well prepare for more substantive ecumenical progress, as well as more substantive theologies. This is a necessary book—vital reading for any theologian.”

— Nicholas M. Healy, St. John’s University“All of the discussions in this book display East’s analytical rigor and theological sophistication. As one of the subjects under discussion in this book, I will speak for all of us and say that there are many times East is able to do more for and with our work than we did ourselves. . . . I look forward to seeing how future theological interpreters take these advances and work with them to push theological interpretation in new and promising directions.”

— Stephen E. Fowl, from the foreword

This book has been more than a decade in the making, being a major revision of my doctoral dissertation at Yale. It’s a pleasure and a relief to hold it in my hands. I’m so eager to see what others make of it. I’m especially grateful for it to be coming out so soon after the release last fall of The Doctrine of Scripture, my first book. The two are complementary volumes: one provides scholarly, theoretical, genealogical, and ecclesiological scaffolding; the other builds a constructive proposal on that basis. The sequence of their release reverses the order in which they were written, but that’s neither here nor there. Together, they comprise about 250,000 words on Christian theology of Holy Scripture and its interpretation. Add in my journal articles and you’ve got 300K words. That’s a lot, y’all. I hope a few folks find something worthwhile in them. Always in service to the church and, ultimately, to the glory of God.

What a joy it is to do this job. Very thankful this evening. Blessings.

Running errata

The first feeling one has upon publishing a book is a mixture of relief and elation, at least ideally. The second is the dawning realization that whatever mistakes one didn’t fix before the manuscript went to the printers are now there, in black and white, forever.

The first feeling one has upon publishing a book is a mixture of relief and elation, at least ideally. The second is the dawning realization that whatever mistakes one didn’t fix before the manuscript went to the printers are now there, in black and white, forever.

Accordingly, I’m going to keep this page as a running list of errata in The Doctrine of Scripture, errors discovered by myself or by readers friendly enough to point them out to me. So far the count is three:

xvi – Liv Stewart Lester (not “Stuart”)

53, footnote 43 – exemplify (not “exemplary”)

77 – magistra (not “magister”)

106, footnote 24 – comes (not “come”)

124 – Rom in first parenthetical citation (chapter and verse cited, no book)

124, footnote 36 – Gospel (not “gospel”)

If you spot any others, fill me in!

Academic support

The academy is often a very lonely place. The work can be grueling, the odds of success long, the competition ferocious, the hours punishing, the pay insufficient, the rewards minuscule, the expectations inhuman, the atmosphere inhumane.

The academy is often a very lonely place. The work can be grueling, the odds of success long, the competition ferocious, the hours punishing, the pay insufficient, the rewards minuscule, the expectations inhuman, the atmosphere inhumane. Often as not you’re alone with a book or a laptop for hours on end, moved by some inner fire to keep chipping away at an insuperable task, secure in the knowledge that what you are doing will be of almost no significance to anyone, ever, living or unborn. Yet chip chip chip, you press on, pounding the proverbial rock.

I have been fortunate—no, the only word is blessed—to have had a uniformly positive experience in the academy. Four years in undergrad, three years in a Master’s program, six years for the doctorate, and now in my fifth year teaching as a professor. In all that time I don’t know that I can point to a single capital-B Bad experience. Not only did I love the work I was doing, the content I was learning, the classes I was taking, the books I was reading. The programs themselves were all healthy environments for a student to inhabit; or at least, to the extent that they contained dysfunction, the dysfunction was no more pronounced than anywhere else, and rarely if ever affected me.

Indeed I think I can say honestly, without an asterisk or whispered anecdotal aside, that I’ve never knowingly been caught up in, or even mildly been touched by, controversy of the typical academic sort that marks and mars so many institutions of higher education. I might even be able to say that I’ve not yet earned an enemy (or a frenemy?) in the academy. I can think of one or two candidates, but that’s probably projection on my part. No doubt my relative lack of enemies—at least who’ve made themselves known to me!—has much more to do with cowardice and a desire to please than any virtue on my part. (If you Enneagram-diagnose me from afar I swear I will cut you down where you stand.) Further, too, at least a partial explanation for this happy state of affairs is my approach to my studies: put your head down, do the work, get out as fast as you can. But mostly I ascribe it to the institutions of which I was a part. The people one learns from and the people one learns alongside make all the difference.

Nevertheless, even the most blissful academic life includes the ordinary challenges that invariably attend it. One of those is the deafening silence, the dark void, that awaits that momentous day when, after years of work, you release something into the world. That something may be a mere review; it may be an essay or an article; occasionally it is a book. And we all know, wherever we find ourselves on the map or continuum of publication-generation, that there’s nothing quite like the long labor of birthing a little, or not so little, intellectual offspring and stepping forward to share it with the world only to hear … nothing. Not a word. Not a peep. Zilch. Nada. Silence.

Even more than bad reviews, it’s being ignored that crouches in the back of your mind, grinning and holding hands with that other ever-lurking demon of academe, imposter syndrome. It’s why academics go to Twitter like moth to a flame: not only because they’re on screens all day with time to kill (and work to avoid), but because proper scholarship usually takes years to produce and still more years to generate feedback. That sweet, sweet dopamine hit of a like or a retweet or a reply is a lot more rewarding than the alternative.

Apart from a general response to one’s work, critical or laudatory or in between, the other thing we academics desperately yearn for but rarely receive is a wide network of support. Or maybe I shouldn’t put it that way. Many friends and colleagues I know do have such networks, though often at great cost, beyond the campus, and as a result of their own intentional efforts. What I mean to say is that specifically academic networks aren’t in general built for emotional and psychological encouragement. They’re more like one long intellectual boot camp. Your drill sergeant has a purpose, and you’re happy (maybe) that he made you who you are; you couldn’t have done it without him. But you don’t go to him when you need a hug.

This is all a lengthy and circuitous prelude to a very small thing I want to share. My first book was published two weeks ago. Along with book #2 (due next April), it was years in the making. In a very real sense I’ve been working toward this finish line since August of 2003. But initially, when the book came in the mail, it felt anticlimactic. There was no link yet on Amazon, no one in the world knew it existed, and certainly no one else had it in their hands (as I did). I wrote the book for others, not myself. Moreover, if we couldn’t throw a party to celebrate, given the pandemic, and if no one online knew about the thing, and it’s not like it’s a trade book meant to fly off the shelves of the local Barnes and Noble—then what to do? How to make the thing feel real, as a shared or social fact and not my own little private achievement?

So in addition to tweeting about the book once the Amazon link came online, I decided to email blast the world, or at least my world. I emailed news about the publication to—I’m not exaggerating—every friend, every extended family member, every church aunt and grandmother who helped raise me, every colleague and academic acquaintance, and every single former teacher (going back 17 years) whose contact info I happened to still have in my Gmail account. I even added scholars who have influenced me through their writing, but whom I have not met in person, or even online. I left out not a soul.

The response was overwhelming. I won’t get into all the details. But suffice it to say that people I haven’t seen or spoken to in over a decade replied with the warmest, sweetest words you can imagine, and certainly more than I was hoping for. And I’m more than willing to own what I was doing: not so much fishing for compliments as wanting quite literally to share in the occasion with others. I wasn’t surprised when my uncle texted to say he’d bought seven copies to give to friends in Dothan, Alabama. I was surprised when this, that, or another laconic, brainy, preternaturally non-emotive senior scholar gushed in congratulations. A lot of “ah, I remember the first one” and “feels like a birth, no?” and “don’t apologize, this calls for celebration!”

What I’m trying to say, what I keep circling around and not quite landing on, is simply this. It was what I needed. And when it came, I wasn’t prepared for it. The bottom fell out, and what I fell into was bottomless gratitude. It’s a wonderful thing, and wonderful in part because of how rare it is, to have people in this bemusing bizarro world of scholarship on one’s side, popping the cork right alongside you. Like your old drill sergeant giving you a bear hug in a crowded restaurant and lifting you off your feet.

The high wears off. You get back to the grindstone. But for a few days there, I was flying.

My new book is out! Order The Doctrine of Scripture today!

My first book, The Doctrine of Scripture, is officially out and ready for purchase. Technically it became available on Friday, August 27, but the book wasn’t yet in my hands and it wasn’t yet available for order online. (Does a book really exist if you can’t add it to your Amazon cart?) But yesterday I received my author’s copies of the book in the mail and the book appeared on Amazon. It’s real! It exists! It’s alive!

My first book, The Doctrine of Scripture, is officially out and ready for purchase. Technically it became available on Friday, August 27, but the book wasn’t yet in my hands and it wasn’t yet available for order online. (Does a book really exist if you can’t add it to your Amazon cart?) But yesterday I received my author’s copies of the book in the mail and the book appeared on Amazon. It’s real! It exists! It’s alive!

Here’s the wonderful cover, as designed by Savanah Landerholm, featuring a watercolor of the annunciation by Gabi Kiss:

And here is the full front and back, along with some of the endorsements:

Speaking of endorsements, I was and remain positively bowled over by the stature and kindness of the scholars—heroes all—who read the book and deigned to say it’s worth a read. That begins with Katherine Sonderegger, whose foreword opens the book. I won’t quote the whole thing, but here’s how it concludes:

The Doctrine of Scripture is a wonderfully ecumenical text. Here we find St. Francis de Sales next to Calvin and Turretin; they in turn next to St. Thomas, St. John of Damascus, St. Cyril, and St. Augustine. Not surprisingly, the list of authors is decidedly pre-modern. East has, it seems, followed C. S. Lewis's dictum ad litteram: Read old books! The book sings. The text displays a clear, poetic style, and wisely reserves the disputation with authors ancient and modern, across several communions, to footnotes. The whole work dedicates itself to showing how Holy Scripture, in its unique yet creaturely status, must be interpreted as the Viva Vox Dei, the living voice of the Living God. The Doctrine of Scripture is an ambitious, learned, and deeply moving work of Ressourcement theology, and I am grateful to have learned from this fine teacher.

The book sings. Can you please carve that on my gravestone? The Great Kate Sonderegger wrote those words. My work is done.

Other brilliant theologians lent a similarly gracious hand to my little book. Here is the inimitable Ephraim Radner:

A magnificent achievement! Brad East has taken his years of theological reflection upon the Bible and crafted a compelling and synoptic discussion of Scripture's divinely granted being and place within the Christian church's life and vision of reality. In the end, East's volume provides a modernized version of a generally classical view of Scripture's form and function, respectfully taking up traditional claims with a critical eye, and weaving old and new perspectives into a lucidly ordered whole that is fundamentally grounded in a living and humble faith. Sprightly written, substantively resourced, carefully argued, and pastorally adept, East's Doctrine of Scripture should be required reading for theological students and scholars alike.

And the redoubtable Bruce Marshall:

It would be hard to imagine a more winsome and helpful introduction to the Christian doctrine of Scripture than this. In an area that has been a minefield of controversy, Brad East writes with clarity yet without polemic, with ecumenical sympathy yet without failing to take a clear position on all the important and contested issues. Whatever your convictions about the Bible and how it should be read, you will benefit from this book.

And the formidable Matthew Levering:

What an exciting book! East's basic moves are recognizable: he carries forward and integrates elements of the doctrines of Scripture of Webster, Boersma, and Jenson. This would be accomplishment enough for a normal book, but East is even bolder ecumenically than the masters upon whom he builds. Without ceasing to value the Reformers, he challenges sola scriptura and the perspicacity of Scripture, and he offers a deeply Catholic account of dogma and apostolicity. This book is a rare gift—a richly comprehensive theology of Scripture that lays the foundation for real ecumenical breakthroughs.

And Darren Sarisky, a once rising star who now is unquestionably one of the leading lights in Christian theology of Scripture:

Brad East writes about the Bible with joy, verve, and insight. His presentation is highly readable, opening the subject up to all those who want to explore a theological perspective on Scripture. His strategy of working from church practice back to the nature and qualities of the text gives us all much to ponder.

And last but not least, Steve Fowl, whom I sometimes affectionately call the pope of the discipline (in his case, theological interpretation of Scripture):

Brad East's The Doctrine of Scripture raises all the key issues for theologians and biblical scholars to think about with regard to the nature and place of Scripture in a Christian theological framework. In a lucid and highly accessible style, he makes a compelling case for why these issues matter for theology and Scriptural interpretation.

When I read those names and their comments, and when that evil demon Imposter isn’t haunting my addled brain, I think, after pinching myself, that maybe I did something right. Or at least wrong in interesting ways. In either case, you should pick up a copy for yourself!

Speaking of which: I’ve buried the lede. You may want to purchase the book from Amazon or some other typical online outlet, but if you buy it from the publisher’s website, you can use the coupon code EASTBK2 to get 40% off the listed price (currently $28). Come on, y’all! You can spare an extra $20 bill for a book that sings, can’t you?

Here, by the way, is a description of the book’s contents:

When Holy Scripture is read aloud in the liturgy, the church confesses with joy and thanksgiving that it has heard the word of the Lord. What does it mean to make that confession? And why does it occasion praise? The doctrine of Scripture is a theological investigation into those and related questions, and this book is an exploration of that doctrine. It argues backward from the church’s liturgical practice, presupposing the truth of the Christian confession: namely, that the canon does in fact mediate the living word of the risen Christ to and for his people. What must be true of the sacred texts of Old and New Testament alike for such confession, and the practices of worship in which it is embedded, to be warranted?

By way of an answer, the book examines six aspects of the doctrine of Scripture: its source, nature, attributes, ends, interpretation, and authority. The result is a catholic and ecumenical presentation of the historic understanding of the Bible common to the people of God across the centuries, an understanding rooted in the church’s sacred tradition, in service to the gospel, and redounding to the glory of the triune God.

Head over to my page dedicated to the book here on the website for further information; I’ll be updating it with links, excerpts, and reviews in the coming weeks, months, and years.

I conceived the idea for this book in the summer of 2018; I drafted it, start to finish, in the fall semester of 2019; I revised it in May/June of 2020, then put the finishing touches on it last December. The copyedits came in May earlier this year, then the proofs a month later, then the physical book a couple months after that. That’s by comparison to my next book, which comes out in April, whose creation will have encompassed a full decade by the time of its publication. (It’s a former dissertation: enough said.)

All that to say: This has been an incredibly fast process, and so it’s somewhat surreal to see the physical book in my hands more or less two years to the day after I began writing it. I’m extremely proud of what I’ve written. I can’t speak to the quality, but I can tell you that it’s my best work. If I have anything whatsoever to say on this topic—if I have any skill in writing or in theological thinking—then you’ll find it on display in this book. I hope you’ll give it a chance. I hope people find it useful, thought-provoking, persuasive, invigorating. But most of all I hope it serves Christ’s church, whose sacred book is my book’s subject matter. That book is Christ’s book, and if my little book leads anyone to understanding or reading or loving it more, or more deeply, then I will be satisfied, and then some.

But right now I’m all gratitude, from top to bottom. So thanks in advance to you, too, if you end up giving it your time.

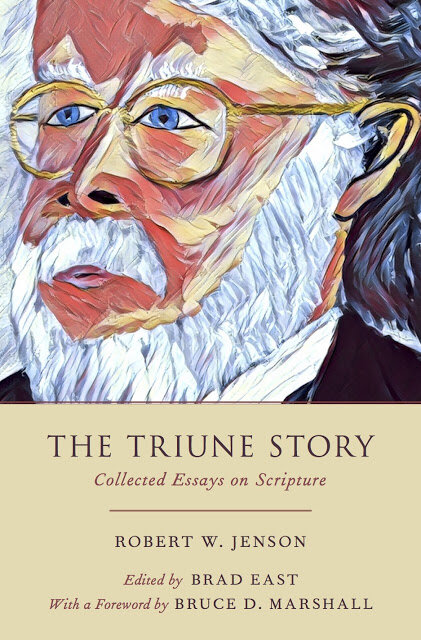

Pre-order The Triune Story today!

Oxford says the book will be out mid-June; Amazon says mid-July. I'd go with Amazon on that one. I'm working on indexing the book right now, after which point, late this month, I'll get the proofs. So perhaps the revised proofs will be ready by May 1? I don't know how quickly the turnaround is on these kinds of books, but perhaps quicker than I imagined. We also need to get the blurbs, about which more soon.

But, anyway, I only just happened upon this bit of news, and I couldn't be more delighted. This volume is going to be a real resource going forward, for Jenson scholars as well as for theologians interested in Scripture more broadly. I can't wait for y'all to have it in your hands.

And speaking of which, pre-order today! And how could you not, gazing on that gorgeous cover (image by the great Chris Green):

Happy news: I'm editing a collection of Jenson's writings on Scripture

My thanks to Cynthia Read and to the editorial team at Oxford for supporting this book. Before his passing earlier this fall, Jens gave the project his blessing, and I hope it is a testament to the beauty and abiding value of his work both for the church and for the theological academy.

My hope is to have the book published by the end of next year, though that obviously depends on many forces outside my control. Perhaps even in time for a session at AAR/SBL...?

In any case, this has been an idea in the back of my mind for a few years now, and it's a joy to see it become a (proleptic) reality. Now y'all just be sure to buy it when it comes out.