Resident Theologian

About the Blog

My latest: why Christians are conspiracy theorists, in CT

A link to my latest column in Christianity Today.

I’ve got a column up this morning in Christianity Today called “Christians Are Conspiracy Theorists.” Here’s a sample:

By any reasonable definition, Christianity is a conspiracy theory. Let’s say it’s a theory of two conspiracies, in fact: the conspiracy of sin, death, and the Devil to put humanity and all creation in “bondage to decay” and the conspiracy by God to liberate creation and redeem his people through Christ (Rom. 8:18–23, RSV throughout).

I realize it seems odd to describe our faith this way, but that’s the proposition I’d like you to ponder. Because if Christianity is a conspiracy theory, then what follows for how believers approach other conspiracy theories in our culture?

Start with a working definition. A conspiracy theory is a form of stigmatized knowledge formally repudiated by elites and/or experts that alleges malign forces behind public events. Knowledge of this truth is kept from the public through official channels and is therefore difficult to prove. As a result, those who learn the truth tend to be suspicious of authorities and may form communities of dissent, or at a minimum be drawn to them. Within these groups, rejecting the public story on a given topic becomes a badge of honor—and belonging.

It seems plain to me that, on this definition, the church’s faith in the gospel qualifies as a conspiracy theory. This was certainly true at its inception, and I think it’s true in our time too.

Click here to read the whole thing.

Readers of the blog may recall of a post on here from back in September 2023 with a similar title. Clearly the idea lodged in my brain; this was a chance to unpack it for a general audience and at length, with a particular view to how Christians behave themselves, so to speak, “epistemically” in the public square and the consequent social dynamics at work. Looking back at that post now, I focused much more then on the spooky, strange, and non-empirical beliefs of Christians: an invisible deity, angels and demons, the blood of a Galilean rebel cleansing an American gentile from his sins against the Creator two thousand years later, and so on. The focus in the CT piece is more about suspect convictions and the way “common sense” functions to ostracize, cordon off, and exclude them—and thus why Christians should be allergic to this strategy when society deploys it about others and tempts us to do the same (even and especially when the convictions in question are genuinely suspect!).

But that’s to summarize in advance; go read the piece for the full argument.

Happy news: Letters to a Future Saint is the runner-up for CT’s Book of the Year!

The headline says it all. Read on for more details!

Yesterday Christianity Today published its annual book awards for 2024. Besides awards for genres like fiction and theology, there is an overall award for Book of the Year. This year’s winner was the great Gavin Ortlund’s What It Means to Be Protestant: The Case for an Always-Reforming Church. And the runner-up?

That would be my own Letters to a Future Saint: Foundations of Faith for the Spiritually Hungry. It won the Award of Merit for Book of the Year!

I’m grateful beyond words. My deepest thanks to the editors and to all who voted. This is not something I or anyone could have expected when I set out to write this book. I’m still in shock about it.

Ideally I’ll wake up soon, because next week there is a special live event celebrating the occasion: a conversation with Russell Moore, Ortlund, and myself, as well as other CT editors. It’ll run for about an hour on YouTube, beginning at 8:00pm ET, and featuring (I believe) questions from readers and subscribers. I’ll see y’all there!

It’s publication day! The Church: A Guide to the People of God is here!

It’s out! At long last! Order a copy today!

It’s out! It’s here! Order a copy! My second book in the same month! There are no more to come anytime soon, so buy them up while you can!

Buy one for yourself, for your spouse, your children, your grandchildren, your nephews, your nieces, your godchildren, your parents, your pastor, your youth pastor, your college pastor, your professor—or all of them!

Don’t take my word for it—listen to Andrew Wilson, Stanley Hauerwas, Ephraim Radner, Karen Kilby, Matthew Levering, Karen Kilby, and Mark Kinzer, all of whom endorsed it. They can’t be wrong, can they?

The first review of the book came out last week in The Gospel Coaliation. Samuel Parkison writes:

Gentiles don’t become Jews, but they can become the true seed of Abraham through adoption (see Gal. 3:16). This deep awareness of the church’s Old Testament connections is a welcome emphasis. All the more so because of the undeniably beautiful prose in which East develops this idea. Indeed, The Church can just as easily be labeled a work of art as a work of theology. For example, his reflections on the typological resonances between Eve, Mary, Israel, and the church are nothing less than riveting.

He concludes: “This is a beautiful book. Taken in such a way, The Church should receive a wide and appreciative readership.”

Come on: There’s just no way a book that looks that good can be bad on the inside. By way of reminder, here is the book’s description:

You belong to God's family. But do you understand what that means?

The Bible tells the story of God and his people. But it is not merely history. It is our story. Abraham is our father. And Israel's freedom from slavery is ours.

Brad East traces the story of God's people, from father Abraham to the coming of Christ. He shows how we need the scope of the entire Bible to fully grasp the mystery of the church. The church is not a building but a body. It is not peripheral or optional in the life of faith. Rather, it is the very beating heart of God's story, where our needs and hopes are found.

Buy it wherever books are sold. And while you’re at it, buy the rest of the volumes in Lexham’s Christian Essentials series—The Apostles’ Creed by Ben Myers, The Lord’s Prayer by Wes Hill, The Ten Commandments and Baptism by Peter Leithart, and God’s Word by John Kleinig. Kleinig also authored the seventh in the series, due next March, called The Lord’s Supper. The last two should come out sometime in the next 12-24 months…

Get the whole set! Starting with mine! Today! Now! Ahorita! S'il vous plaît!

Thanks to all. This one’s a love letter to the church—both the Church and the churches that I have called home over the last four decades. I hope it shows.

Some news: Calvin, Comment, & sabbatical

Three bits of professional news.

Some professional news to share; three items to be exact:

1. Earlier this year I was awarded a Teacher-Scholar Grant by the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship. The grant is called “Vital Worship, Vital Preaching” and runs from May 1, 2024, to May 1, 2025. My project is the research for my next book, Technology: For the Care of Souls. Worship is the locus and gravitational center for practical Christian questions about technology, not least what is permissible or useful in the liturgy and why. I’m grateful to be supported by Calvin as I pursue these questions.

2. Recently Comment magazine announced a slate of twelve new Contributing Editors, of whom I am one. The others are Amber Lapp, Angel Adams Parham, Brandon Vaidyanathan, Christine Emba, Daniel Bezalel Richardsen, Elizabeth Oldfield, Jennifer Banks, John Witvliet, L. M. Sacasas, Louis Kim, and Luke Bretherton. I’m honored to be counted among them. Last month we gathered at the glorious Laity Lodge (just three hours south of Abilene) together with the entire Comment editorial team, along with regular contributors, stakeholders, and Cardus folks. It was wonderful. Check out the new Manifesto guiding the vision of the magazine under editor Anne Snyder. Subscribe today!

3. I am currently on research leave at ACU. The sabbatical covers both semesters in the academic year—really, from early May 2024 through August 2025, it amounts to sixteen months outside the classroom. This was made possible by the generosity of both ACU and dozens of donors, not to mention the support of my chair, dean, and provost. I was busy with family and vacation this summer, so it hasn’t felt like the sabbatical had truly begun until the last three weeks. It’s a relief, to say the least. Teaching a 4/4 is not a death sentence, as I’ve tirelessly repeated; but it’s still taxing. As I said above, this year I’m preparing a manuscript, due to Lexham next August, on the challenges of digital technology for church leadership, pastoral ministry, and public worship. Besides my normal writing for Christianity Today and other outlets, three-fourths of my working hours are currently devoted to reading and thinking about technology and related topics.

That, and doing publicity and podcasts for my two new books coming out next month (in 23 and 45 days, respectively!). It’s a busy time, but a very, very good one. I’m thankful.

Letters to a Future Saint: cover, blurbs, pub date, and more!

The title says it all. Click on to see the cover and endorsements and more!

I’m pleased to announce that my next book, Letters to a Future Saint: Foundations of Faith for the Spiritually Hungry, has an official publication date, a cover, blurbs galore, and more. It’s due October 1. Now feast your eyes:

Isn’t that lovely? The theme continues on the inside, too; I can’t wait for folks to see how it’s designed.

Here’s the official book description:

An invitation to the Christian faith for the bored, the distracted, and the spiritually hungry

Dear future saint,

Why is the gospel worth living for?

Why is it worth dying for?

In these letters, a fellow pilgrim addresses future saints: the bored and the distracted, the skeptical and the curious, the young and the spiritually hungry. Lively and readable, these bite-sized letters explain the basics of Christian life, including orthodox doctrine, the story of Scripture, the way of discipleship, and more.

Interweaving Scripture, poetry, and theological writings, Letters to a Future Saint educates readers in the richness of the Christian tradition. But beyond that, this earnest and approachable volume offers young people— who may be largely uninformed of the depths of faith despite having been raised in Christian homes —an invitation into the life of the church and into a deeper relationship with God.

And here are the endorsements, which—well, just read on:

“Rule number one in sharing the Christian faith with young people: don’t patronise. Assume they are morally serious and intellectually curious; that they are in search of a structure that will carry the weight of their anxieties, passions and imaginative energy. And if you start from that sort of point, the book you might well want to put into their hands is something very like this one—clear, respectful, challenging, candid, gracious.”

—Rowan Williams, 104th Archbishop of Canterbury“In this little book, East teaches about the gospel—he catechizes. But its epistolary format allows what could seem tiresome or didactic to become conversational and approachable. These letters tell the story of Jesus in many ways, from many different angles, and with a lightness of touch. They also convey what it might feel like to be a Christian and to think about the world in light of the story of Jesus. If you are someone who cares about young people or those of any age finding their way in the spiritual life—if you care about future saints—read this book and share it with others.”

—Tish Harrison Warren, author of Liturgy of the Ordinary and Prayer in the Night“The letters that Brad East writes here are signed, ‘Yours in Christ, a fellow pilgrim,’ and that tells you most of what you need to know about this wonderful book. It’s a warmhearted, clear-sighted account of life ‘in Christ,’ not pronounced from on high, but narrated by someone a little farther along the Way than the young people it’s addressed to. This is a book to give to many of those pilgrims near the outset of their journey.”

—Alan Jacobs, Jim and Sharon Harrod Chair of Christian Thought, Baylor University“Sometimes catechisms seem to emphasize truth at the expense of life. The parroting back of doctrinal answers to posed questions, while often valuable, can be dangerous for those tempted to think of Christianity as the mastery of syllogisms rather than as the Way of the Cross. In this book, Brad East takes us along as he guides a young pilgrim in the path that is Jesus. Reading this will help you see your own faith with fresh eyes and will prompt you to be not just a disciple but a discipler.”

—Russell Moore, editor in chief, Christianity Today“Brad East does not cease to astound. This book is both spiritual meditation and pocket catechism—it instructs as it inspires, and its contents explain Christianity in a way both simple and profound. This is the kind of book to spread around everywhere: airports, homes, churches, used bookstores, universities, and so on. Professor East has something important to teach each one of us!”

—Matthew Levering, James N. Jr. and Mary D. Perry Chair of Theology, Mundelein Seminary“In this time of widespread unclarity, Brad East’s insightful letters help us see what being a Christian might look like. A fascinating book that helps us see the fascinating character of our faith.”

—Stanley Hauerwas, Gilbert T. Rowe Professor Emeritus of Divinity and Law, Duke University“A personal, readable, informed, and confident exposition of the Christian faith—so confident, in fact, that it starts and ends with an invitation to martyrdom in the service of Christ! East’s unwillingness to make Christ into a founder of a ‘religion of comfortableness’ (Nietzsche) is admirable.”

—Miroslav Volf, Henry B. Wright Professor of Systematic Theology, Yale Divinity School

I have no words. I swung for the fences, and somehow managed multiple grand slams. I’m speechless. I’ve been reading these writers since seminary, some for going on two decades. It’s such an honor to have their endorsements for this book. Thanks to them and to all who decide to give the book a chance based on their recommendation.

Letters to a Future Saint is out in just over five months. (Three weeks later my other new book, The Church: A Guide to the People of God, will be published. When it rains, it pours!) You can pre-order it wherever you prefer: Eerdmans, Christianbook, Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon. Or pre-order a copy from each just to be safe! Your call.

This book’s publication is a dream come true, in more ways than one. I’m beyond excited to share it with readers. I hope you’ll be one, and will share it with others.

The Church: cover, blurbs, pub date, and Amazon pre-order page!

Sharing the cover, blurbs, and publication date for my new book The Church: A Guide to the People of God.

Habemus cover! And publication date! And blurbs! And more!

The book in question is The Church: A Guide to the People of God. It’s the sixth in Lexham’s Christian Essentials series. Here’s the cover:

Just … wow. Perfect. The Lexham folks really know what they’re doing. (For comparison, here are the other covers in the series.)

How about some blurbs? Here they are, in all their glory. Allow me to find my fainting couch before reading them again:

This is a bright, thoughtful and passionate account of the church. Brad East roots ecclesiology in the story of Israel and the story of Jesus Christ, and in doing so provides a number of fresh perspectives which can help us in our doctrine and our practice.

—Andrew Wilson, teaching pastor at King's Church LondonThis book is pure delight! Inspiring, instructive, enriching, beautifully written, this book makes one want to be a Christian. It is next to impossible to write an ecumenically rewarding book on the theology of the church, but Brad East has done it!

—Matthew Levering, James N. Jr. and Mary D. Perry Chair of Theology, Mundelein SeminaryBrad East's account of Mary as the firstborn of the Church is brilliant. The theology in this book is at once scriptural and creative. With this book East becomes one of the more important theologians writing today.

—Stanley Hauerwas, Professor (retired), Duke Divinity SchoolI find this an extraordinary book. It is short. It is written with simplicity and clarity. And yet it covers so much, introducing its readers to an extraordinarily rich field of theology.

—Karen Kilby, Bede Professor of Catholic Theology, Durham UniversityIn twelve concise, accessible, penetrating, and artistically-crafted chapters, Brad East provides an introductory guide to the Church as the messianic expansion of Israel among the nations of the earth. Rooting the identity of the Church in the biblical story of God's love for Israel, East shows how the redemptive work of Jesus completes that story, and is incomprehensible apart from that story. This introduction to the Church is both simple and profound—like the good news itself, which the Church proclaims and embodies.

—Mark Stephen Kinzer, moderator of Yachad BeYeshua, an international interconfessional fellowship of Jewish disciples of Yeshua, and Senior Scholar and President Emeritus of Messianic Jewish Theological InstituteBrad East's The Church wonderfully enhances the already marvelous Lexham series on Christian "Essentials." Building off of the Church's "Mystery" that is Christ's Body, as Ephesians proclaims, East outlines the story of God's people born of Abraham, in its breadth, beauty, imperative, and promise. Lucid, compact, attractive, and appropriately rich with the figures of Scripture's visionary treasure, this book is not only a fine introduction for new Christians of all traditions, but a well from which to draw continued reflection and prayerful praise. Highly commended!

—Ephraim Radner, Professor of Historical Theology, Wycliffe College at the University of Toronto

There are no words. My thanks to each of them for taking the time to read the manuscript and for their remarkable kindness. I hope other readers feel similarly!

Here is the official description of the book (written by Lexham, not by me):

You belong to God's family. But do you understand what that means?

The Bible tells the story of God and his people. But it is not merely history. It is our story. Abraham is our father. And Israel's freedom from slavery is ours.

Brad East traces the story of God's people, from father Abraham to the coming of Christ. He shows how we need the scope of the entire Bible to fully grasp the mystery of the church. The church is not a building but a body. It is not peripheral or optional in the life of faith. Rather, it is the very beating heart of God's story, where our needs and hopes are found.

That captures perfectly what I’m up to in the book. Short and sweet.

If any of the above piques your interest, here’s the good news: the book is up on Amazon and available for pre-order. As for when it’s coming out…

The publication date is October 23. That’s 39 weeks from now. A long time to wait. So why not make sure it’ll be in your mailbox on time?

Can you tell I’m excited? I’m excited. This is all not even to mention the fact that my other book coming out this fall also has its official cover and a publication date (let’s just say it’s not far off from this one). But I’ll save that announcement for another day, particularly once it too is up on Amazon and I’ve got blurbs and galleys in hand.

Until then. Thanks to everyone, but above all to Todd Hains, who made this happen from start to finish. He’s the man.

*

Update: I neglected to add two things.

First, head here for a webpage dedicated to the book. I’ll also add/share links to the publisher’s website for folks who want to check it out there or who want to avoid giving money to Mr. Bezos.

Second, I forgot to include the table of contents for those interested in such things. Here you go:

Series Preface

Prayers of the People1. Mystery

2. Mother

3. Chosen

4. Bound

5. Redeemed

6. Holy

7. Ruled

8. Beloved

9. Incarnate

10. Sent

11. Entrusted

12. BenedictionAcknowledgments

Permissions

Notes

Worked Cited

Author Index

Scripture Index

Update on my next two books

An update on my next two books, both due next year. The first is called The Church: A Guide to the People of God; the second is called Letters to a Future Saint: A Catechism for Believers on the Way.

My first two books, The Doctrine of Scripture and The Church’s Book, were published in August 2021 and April 2022, respectively, just eight months apart. Now it’s looking like the next two will be published in a similarly short span.

Book #3 is titled The Church: A Guide to the People of God. It’s in the Christian Essentials series published by Lexham Press; it’ll be the sixth of nine total volumes. The first five cover the Apostles’ Creed (Ben Myers), the Ten Commandments (Peter Leithart), the Lord’s Prayer (Wesley Hill), baptism (Peter Leithart), and the Bible (John Kleinig). The remaining three address the liturgy, the Eucharist, and the forgiveness of sins. The whole series will eventually form a trilogy of trilogies: Creed–Prayer–Decalogue; Church–Scripture–Liturgy; Baptism–Eucharist–Absolution.

I worked out the final version of the manuscript with the wonderful Todd Hains last April, and sometime in the next few weeks I’ll receive and approve the copy-edited proofs before they’re handed on to be typeset. We’re expecting the book to come out next spring (if I’m guessing, let’s say March 25, 2024—the book begins with the Annunciation, after all).

Book #4 is titled Letters to a Future Saint: A Catechism for Believers on the Way. I finished a draft this past May, sat on it over the summer, got feedback from readers, and made final revisions this month. Two days ago I emailed it to James Ernest at Eerdmans (James is the reason I wrote this book in the first place). Obviously he and the other Eerdmans editors have to like the book and formally approve it. On the assumption they will and do, with however many suggested changes, the book should come out late fall next year (let’s say October 1, 2024, since Saint Thérèse is a kind of patroness for the book—though to be honest, my guess would be mid-November, just before AAR/SBL/Thanksgiving/Advent).

Both books are meant for lay readers of all ages. I was just telling someone yesterday that writing for a popular audience is both harder and more fun to write than anything else. It requires intense discipline not to indulge all your bad habits: not to say everything; not to use jargon; not to presuppose background knowledge, but also not to overwhelm—all while holding the reader’s attention with shorter sentences and paragraphs and chapters, without the crutch of ten trillion ego-padding footnotes.

Each book is an outgrowth of my time in the classroom here at ACU. I have taught the same upper-level course on ecclesiology every fall semester since 2017. The Church is simply that class rendered in print. My special hope is that it reaches readers who love Christ but don’t understand why His body and bride matters; or who “get” the Church but don’t “get” Abraham and Moses and Israel. Let me be the one to tell them!

Letters to a Future Saint is meant for anyone old enough to read it—from high schoolers to senior citizens—but the primary audience I have in mind is the students I teach every day. On one hand, they mostly don’t read books; they largely come from Bible Belt contexts; they’re typically non-denom evangelicals; they’re baptized but uncatechized. On the other hand, they’re earnest, hungry, and eager to learn; they know Christ and want to know Him more; they’re willing to labor and struggle to get there. In other words, they’re young people in the orbit of the Church but in need of meat, not milk. I want to catechize them. I want my book to be a tool in the hands of professors, pastors, parents, grandparents, mentors, volunteers, youth groups, study groups, Bible studies, Christian colleges, and Christian study centers. I want older believers to say, “This is a book that will draw you into the depths of the faith—a book you can understand, a book you’ll enjoy, yet also a book that will show you why living and dying for Christ makes sense.” That’s a high goal, and I’ve surely failed to meet it in countless ways, but it’s my hope nonetheless.

In both books I have sought to be ecumenical without being generic; I have tried, that is, to be at once biblical, creedal, evangelical, and catholic. My Catholic friends observed how saturated the manuscripts are with the Old Testament; my evangelical friends noted how capital-O Orthodox they seem; my academic friends were struck by the devotional and even pious tone. Lord willing, these add up to a holistic whole and not a false eclecticism. I want readers of all backgrounds to find profit in what I’ve written. And even when something is foreign or initially off-putting, I long for it not to lead them to put down the book, but to keep reading to learn more.

Now to wait. Next year feels a long ways off. What am I supposed to do with my time when I’m not obsessively breathlessly writing rewriting revising two books simultaneously? I guess we’ll see.

A new book contract! And other coming attractions

Happy news to share about a new book contract with Eerdmans! Plus a list of additional forthcoming writing projects: other books as well as essays and reviews.

It’s official!

This week I received and signed the contract for my next book. Eerdmans is publishing it, and the tentative publication date is late 2024. The title is Letters to a Future Saint: A Catechism for Young Believers. It is what it sounds like: an epistolary catechism intended for readers in their late teens or early twenties. Not an apologetics for nonbelievers, but a catechism for would-be believers, folks who’ve grown up in the church, or perhaps in its orbit, but are relatively ignorant about the ABCs of the Christian faith while hungry to learn more.

I drafted a good two-thirds of the book in a brief but intense span of time last year, then sat on it. Now that the contract’s official, the writing will re-commence forthwith. I hope to have a rough draft by this summer, and then it’ll be time to revise the manuscript to the death. I want this thing to be perfect—by which I mean, not perfect, but absolutely accessible to my intended audience, and not only accessible, but appealing, fascinating, stimulating, even converting. I want not one word out of place. So I’m sure I’ll be road-testing it on some students in the summer and fall.

I’ve known this was coming down the pike for a while, but I didn’t want to make an announcement until it was for sure. I couldn’t be more excited. I can’t wait to share the final product with the world. I hope it finds a real readership and makes a real difference, however modest.

*

While we’re on the topic, here is a larger update on other writing projects, whether books or essays, imminent or far off.

–My first two books were published in the fall and spring of 2021 and 2022, respectively. The first was about the Bible. The second was about the Bible and the church. Book #3, not yet released, is about the church. (Are you sensing a theme?)

That book is written and in the hands of the publisher. It’s called The Church: A Guide to the People of God, and it will be the sixth entry in Lexham’s Christian Essentials series. The first five treat the Apostles’ Creed (Ben Myers), The Ten Commandments (Peter Leithart), The Lord’s Prayer (Wesley Hill), baptism (Leithart again), and the Bible (John Kleinig). I’ve read all of them, and each is fantastic. I’ve assigned more than one of them many times in classes. I’m honored to join the series. I’m eager to read the entry on the Eucharist, whoever ends up writing it!

The publication date for my entry on the church is TBD, but my guess is sometime between December 2023 and March 2024.

–Book #4 is my big news above, and as I said, I expect it to be released sometime between late 2024 and early 2025.

–Book #5 is not news, as I signed the contract nearly two years ago. It will likewise be with Lexham, in another series called Lexham Ministry Guides. The subtitle for the series and for each book in it is For the Care of Souls. Four have been published so far: on funerals, stewardship, pastoral care, and spiritual warfare.

My entry in the series will be on the topic of technology. Specifically, the role and challenge of digital technology in the life of pastoral ministry. It’s a topic close to my heart and one I’ve developed a class on here at ACU. The book will be midsize and written for ordained pastors in formal church ministry of some kind. I hope it will not be like other books of this sort. We shall see.

Anyway, I expect that book to be published in the spring or summer of 2026. And beyond that, while I have more book ideas germinating—one in particular, a “big” scholarly one—no contracts or hard plans are in place. I’d be surprised if I didn’t take a bit of a break after this one. After all, if everything goes according to plan, and God is so gracious as to permit it, I’ll have published five books in a stretch of about five years. That’s a lot. Readers, editors, and publishers will have to tell me at that point whether they want more from me, or whether that’s good enough, thank you very much.

*

As for other writing…

–My most recent peer-reviewed journal article came out last fall. I don’t currently have another one teed up, but I do have an idea for one. I’m going to let it ruminate for a while. It’s about Israel, the church, the Torah, and Saint Paul.

–In the next print issue of Mere Orthodoxy I have an essay called “Once More, Church and Culture.” It’s a reflection on Christendom, America, Niebuhr, and James Davison Hunter. Not quite an intervention, but I do offer a constructive proposal.

–In the print edition of First Things I have a reflection forthcoming on what it means to do theology when the church is divided, as it is today. This one’s a long time coming, because it is an answer to a question I get all the time about my ecclesial identity. I’m pleased to see it in the magazine, a first for me.

–This summer I have a chapter in a book published by Plough on the liberal arts. The volume came out of the grant project I was a part of called The Liberating Arts. More on this one soon.

–This summer I am writing a chapter for a book due to be published in 2024 dedicated to the topic of teaching theology. I won’t say much more about it at the moment, but I’m positively giddy to be included in the volume. Anyone in theology will recognize pretty much every name in the collection—minus mine. I still can’t believe I was invited to contribute. And I love the idea of theologians writing about teaching, which is a practice too many of us were trained to avoid or at least to resent the necessity of.

–Later this month (or next), I’ll be part of a symposium in Syndicate on Miroslav Volf and Ryan McAnnally-Linz’s new book The Home of God: A Brief Story of Everything. Should be good fun.

–Later this spring I should have a review essay in The Christian Century on Mark Noll’s book America’s Book: The Rise and Decline of a Bible Civilization.

–Possibly this spring or summer I might have an essay in The Point that uses Wendell Berry’s new book on race, home, and patriotism as a point of departure. I’ve got the green light, but I also have to sit down and do the thing…

–In Restoration Quarterly I plan to publish an essay on churches of Christ, evangelicalism, and catholicity, building on and synthesizing my series here on the blog last summer/fall.

–In the Journal of Christian Studies I plan to write a defense of holy orders from and for a low-church context that spurns ordination and affirms the priesthood of all believers.

–In Comment I’ll be writing a review essay of Christopher Watkin’s Biblical Critical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture. Kudos to Brian Dijkema, editor extraordinaire, for nudging me into it.

–My review of Jordan Senner’s book on John Webster just came out in Scottish Journal of Theology.

–My review of David Kelsey’s Human Anguish and God’s Power is with the editors at the Stone-Campbell Journal; I imagine it’ll be published later this year.

–My review of Fred Sanders’ Fountain of Salvation is with the editors at Pro Ecclesia; should be published soon.

–Same for my review of R. B. Jamieson and Tyler Wittman’s Biblical Reasoning, to be published in the International Journal of Systematic Theology.

–I’ll soon be writing a (long) review of Konrad Shmid and Jens Schrötter’s The Making of the Bible for the journal Interpretation.

–I’ve already recorded an interview for the podcast The Great Tradition; the episode should drop by month’s end.

–I’m giving talks here and there, in Abilene and elsewhere, but nothing to advertise here.

And I think that’s it. For now. Thanks for reading. Much to come. Now back to work.

Six months without podcasts

Last September I wrote a half-serious, half-tongue-in-cheek post called “Quit Podcasts.” There I followed my friend Matt Anderson’s recommendation to “Quit Netflix” with the even more unpopular suggestion to quit listening to podcasts. As I say in the post, the suggestion was two-thirds troll, one-third sincere. That is, I was doing some public teasing, poking the bear of everyone’s absolutely earnest obsession with listening to The Best Podcasts all day every day.

Last September I wrote a half-serious, half-tongue-in-cheek post called “Quit Podcasts.” There I followed my friend Matt Anderson’s recommendation to “Quit Netflix” with the even more unpopular suggestion to quit listening to podcasts. As I say in the post, the suggestion was two-thirds troll, one-third sincere. That is, I was doing some public teasing, poking the bear of everyone’s absolutely earnest obsession with listening to The Best Podcasts all day every day. Ten years ago, in a group of twentysomethings, the conversation would eventually turn to what everyone was watching. These days, in a group of thirtysomethings, the conversation inexorably turns to podcasts. So yes, I was having a bit of fun.

But not only fun. After 14 years of listening to podcasts on a more or less daily basis, I was ready for something new. Earlier in the year I’d begun listening to audiobooks in earnest, and in September I decided to give up podcasts for audiobooks for good—or at least, for a while, to see how I liked it. Going back and forth between audiobooks and podcasts had been fine, but when the decision is between a healthy meal and a candy bar, you’re usually going to opt for the candy bar. So I cut out the treats and opted for some real food.

That was six months ago. How’s the experiment gone? As well as I could have hoped for. Better, in fact. I haven’t missed podcasts once, and it’s been nothing but a pleasure making time for more books in my life.

Now, before I say why, I suppose the disclaimer is necessary: Am I pronouncing from on high that no one should listen to podcasts, or that all podcasts are merely candy bars, or some such thing? No. But: If you relate to my experience with podcasts, and you’re wondering whether you might like a change, then I do commend giving them up. To paraphrase Don Draper, it will shock you how much you won’t miss them, almost like you never listened to them in the first place.

So why has it been so lovely, life sans pods? Let me count the ways.

1. More books. In the last 12 months I listened to two dozen works of fiction and nonfiction by C. S. Lewis and G. K. Chesterton alone. Apart from the delight of reading such wonderful classics again, what do you think is more enriching for my ears and mind? Literally any podcast produced today? Or Lewis/Chesterton? The question answers itself.

2. Not just “more” books, but books I wouldn’t otherwise have made the time to read. I listened to Fahrenheit 451, for example. I hadn’t read it since middle school. I find that I can’t do lengthy, complex, new fiction on audio, but if it’s a simple story, or on the shorter side, or one whose basic thrust I already understand, it goes down well. I’ve been in a dystopian mood lately, and felt like revisiting Bradbury, Orwell, Huxley, et al. But with a busy semester, sick kids, long evenings, finding snatches of time in which to get a novel in can be difficult. But I always have to clean the house and do the dishes. Hey presto! Done and done. Many birds with one stone.

3. Though I do subscribe to Audible (for a number of reasons), I also use Libby, which is a nice way to read/listen to new books without buying them. That’s what I did with Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks—another book that works well on audio. I’ve never been much of a local library patron, except for using university libraries for academic books. This is one way to patronize my town’s library system while avoiding spending money I don’t have on books I may not read anytime soon.

4. I relate to Tyler Cowen’s self-description as an “infogore.” Ever since I was young I have wanted to be “in the know.” I want to be up to date. I want to have read and seen and heard all the things. I want to be able to remark intelligently on that op-ed or that Twitter thread or that streaming show or that podcast. Or, as it happens, that unprovoked war in eastern Europe. But it turns out that Rolf Dobelli is right. I don’t need to know any of that. I don’t need to be “in the know” at all. Seven-tenths is evanescent. Two-tenths is immaterial to my life. One-tenth I’ll get around to knowing at some point, though even then I will, like everyone else, overestimate its urgency.

That’s what podcasts represent to me: either junk food entertainment or substantive commentary on current events. To the extent that that is what podcasts are, I am a better person—a less anxious, more contemplative, more thoughtful, less showy—for having given them up.

Now, does this description apply to every podcast? No. And yet: Do even the “serious” podcasts function in this way more often than we might want to admit? Yes.

In any case, becoming “news-resilient,” to use Burkeman’s phrase, has been one of the best decisions I’ve made in a long time. My daily life is not determined by headlines—print, digital, or aural. Nor do I know what the editors at The Ringer thought of The Batman, or what Ezra Klein thinks of Ukraine, or what the editors at National Review think of Ukraine. The truth is, I don’t need to know. Justin E. H. Smith and Paul Kingsnorth are right: the number of people who couldn’t locate Ukraine on a map six weeks ago who are now Ukraine-ophiles with strong opinions about no-fly zones and oil sanctions would be funny, if the phenomenon of which they are a part weren’t so dangerous.

I don’t have an opinion about Ukraine, except that Putin was wrong to invade, is unjust for having done so, and should stop immediately. Besides praying for the victims and refugees and for an immediate cessation to hostilities, there is nothing else I can do—and I shouldn’t pretend otherwise. That isn’t a catchall prohibition, as though others should not take the time, slowly, to learn about the people of Ukraine, Soviet and Russian history, etc., etc. Anyone who does that is spending their time wisely.

But podcasts ain’t gonna cut it. Even the most sober ones amount to little more than propaganda. And we should all avoid that like the plague, doubly so in wartime.

The same goes for Twitter. But then, I quit that last week, too. Are you sensing a theme? Podcasts aren’t social media, but they aren’t not social media, either. And the best thing to do with all of it is simple.

Sign off.

Academic support

The academy is often a very lonely place. The work can be grueling, the odds of success long, the competition ferocious, the hours punishing, the pay insufficient, the rewards minuscule, the expectations inhuman, the atmosphere inhumane.

The academy is often a very lonely place. The work can be grueling, the odds of success long, the competition ferocious, the hours punishing, the pay insufficient, the rewards minuscule, the expectations inhuman, the atmosphere inhumane. Often as not you’re alone with a book or a laptop for hours on end, moved by some inner fire to keep chipping away at an insuperable task, secure in the knowledge that what you are doing will be of almost no significance to anyone, ever, living or unborn. Yet chip chip chip, you press on, pounding the proverbial rock.

I have been fortunate—no, the only word is blessed—to have had a uniformly positive experience in the academy. Four years in undergrad, three years in a Master’s program, six years for the doctorate, and now in my fifth year teaching as a professor. In all that time I don’t know that I can point to a single capital-B Bad experience. Not only did I love the work I was doing, the content I was learning, the classes I was taking, the books I was reading. The programs themselves were all healthy environments for a student to inhabit; or at least, to the extent that they contained dysfunction, the dysfunction was no more pronounced than anywhere else, and rarely if ever affected me.

Indeed I think I can say honestly, without an asterisk or whispered anecdotal aside, that I’ve never knowingly been caught up in, or even mildly been touched by, controversy of the typical academic sort that marks and mars so many institutions of higher education. I might even be able to say that I’ve not yet earned an enemy (or a frenemy?) in the academy. I can think of one or two candidates, but that’s probably projection on my part. No doubt my relative lack of enemies—at least who’ve made themselves known to me!—has much more to do with cowardice and a desire to please than any virtue on my part. (If you Enneagram-diagnose me from afar I swear I will cut you down where you stand.) Further, too, at least a partial explanation for this happy state of affairs is my approach to my studies: put your head down, do the work, get out as fast as you can. But mostly I ascribe it to the institutions of which I was a part. The people one learns from and the people one learns alongside make all the difference.

Nevertheless, even the most blissful academic life includes the ordinary challenges that invariably attend it. One of those is the deafening silence, the dark void, that awaits that momentous day when, after years of work, you release something into the world. That something may be a mere review; it may be an essay or an article; occasionally it is a book. And we all know, wherever we find ourselves on the map or continuum of publication-generation, that there’s nothing quite like the long labor of birthing a little, or not so little, intellectual offspring and stepping forward to share it with the world only to hear … nothing. Not a word. Not a peep. Zilch. Nada. Silence.

Even more than bad reviews, it’s being ignored that crouches in the back of your mind, grinning and holding hands with that other ever-lurking demon of academe, imposter syndrome. It’s why academics go to Twitter like moth to a flame: not only because they’re on screens all day with time to kill (and work to avoid), but because proper scholarship usually takes years to produce and still more years to generate feedback. That sweet, sweet dopamine hit of a like or a retweet or a reply is a lot more rewarding than the alternative.

Apart from a general response to one’s work, critical or laudatory or in between, the other thing we academics desperately yearn for but rarely receive is a wide network of support. Or maybe I shouldn’t put it that way. Many friends and colleagues I know do have such networks, though often at great cost, beyond the campus, and as a result of their own intentional efforts. What I mean to say is that specifically academic networks aren’t in general built for emotional and psychological encouragement. They’re more like one long intellectual boot camp. Your drill sergeant has a purpose, and you’re happy (maybe) that he made you who you are; you couldn’t have done it without him. But you don’t go to him when you need a hug.

This is all a lengthy and circuitous prelude to a very small thing I want to share. My first book was published two weeks ago. Along with book #2 (due next April), it was years in the making. In a very real sense I’ve been working toward this finish line since August of 2003. But initially, when the book came in the mail, it felt anticlimactic. There was no link yet on Amazon, no one in the world knew it existed, and certainly no one else had it in their hands (as I did). I wrote the book for others, not myself. Moreover, if we couldn’t throw a party to celebrate, given the pandemic, and if no one online knew about the thing, and it’s not like it’s a trade book meant to fly off the shelves of the local Barnes and Noble—then what to do? How to make the thing feel real, as a shared or social fact and not my own little private achievement?

So in addition to tweeting about the book once the Amazon link came online, I decided to email blast the world, or at least my world. I emailed news about the publication to—I’m not exaggerating—every friend, every extended family member, every church aunt and grandmother who helped raise me, every colleague and academic acquaintance, and every single former teacher (going back 17 years) whose contact info I happened to still have in my Gmail account. I even added scholars who have influenced me through their writing, but whom I have not met in person, or even online. I left out not a soul.

The response was overwhelming. I won’t get into all the details. But suffice it to say that people I haven’t seen or spoken to in over a decade replied with the warmest, sweetest words you can imagine, and certainly more than I was hoping for. And I’m more than willing to own what I was doing: not so much fishing for compliments as wanting quite literally to share in the occasion with others. I wasn’t surprised when my uncle texted to say he’d bought seven copies to give to friends in Dothan, Alabama. I was surprised when this, that, or another laconic, brainy, preternaturally non-emotive senior scholar gushed in congratulations. A lot of “ah, I remember the first one” and “feels like a birth, no?” and “don’t apologize, this calls for celebration!”

What I’m trying to say, what I keep circling around and not quite landing on, is simply this. It was what I needed. And when it came, I wasn’t prepared for it. The bottom fell out, and what I fell into was bottomless gratitude. It’s a wonderful thing, and wonderful in part because of how rare it is, to have people in this bemusing bizarro world of scholarship on one’s side, popping the cork right alongside you. Like your old drill sergeant giving you a bear hug in a crowded restaurant and lifting you off your feet.

The high wears off. You get back to the grindstone. But for a few days there, I was flying.

My new book is out! Order The Doctrine of Scripture today!

My first book, The Doctrine of Scripture, is officially out and ready for purchase. Technically it became available on Friday, August 27, but the book wasn’t yet in my hands and it wasn’t yet available for order online. (Does a book really exist if you can’t add it to your Amazon cart?) But yesterday I received my author’s copies of the book in the mail and the book appeared on Amazon. It’s real! It exists! It’s alive!

My first book, The Doctrine of Scripture, is officially out and ready for purchase. Technically it became available on Friday, August 27, but the book wasn’t yet in my hands and it wasn’t yet available for order online. (Does a book really exist if you can’t add it to your Amazon cart?) But yesterday I received my author’s copies of the book in the mail and the book appeared on Amazon. It’s real! It exists! It’s alive!

Here’s the wonderful cover, as designed by Savanah Landerholm, featuring a watercolor of the annunciation by Gabi Kiss:

And here is the full front and back, along with some of the endorsements:

Speaking of endorsements, I was and remain positively bowled over by the stature and kindness of the scholars—heroes all—who read the book and deigned to say it’s worth a read. That begins with Katherine Sonderegger, whose foreword opens the book. I won’t quote the whole thing, but here’s how it concludes:

The Doctrine of Scripture is a wonderfully ecumenical text. Here we find St. Francis de Sales next to Calvin and Turretin; they in turn next to St. Thomas, St. John of Damascus, St. Cyril, and St. Augustine. Not surprisingly, the list of authors is decidedly pre-modern. East has, it seems, followed C. S. Lewis's dictum ad litteram: Read old books! The book sings. The text displays a clear, poetic style, and wisely reserves the disputation with authors ancient and modern, across several communions, to footnotes. The whole work dedicates itself to showing how Holy Scripture, in its unique yet creaturely status, must be interpreted as the Viva Vox Dei, the living voice of the Living God. The Doctrine of Scripture is an ambitious, learned, and deeply moving work of Ressourcement theology, and I am grateful to have learned from this fine teacher.

The book sings. Can you please carve that on my gravestone? The Great Kate Sonderegger wrote those words. My work is done.

Other brilliant theologians lent a similarly gracious hand to my little book. Here is the inimitable Ephraim Radner:

A magnificent achievement! Brad East has taken his years of theological reflection upon the Bible and crafted a compelling and synoptic discussion of Scripture's divinely granted being and place within the Christian church's life and vision of reality. In the end, East's volume provides a modernized version of a generally classical view of Scripture's form and function, respectfully taking up traditional claims with a critical eye, and weaving old and new perspectives into a lucidly ordered whole that is fundamentally grounded in a living and humble faith. Sprightly written, substantively resourced, carefully argued, and pastorally adept, East's Doctrine of Scripture should be required reading for theological students and scholars alike.

And the redoubtable Bruce Marshall:

It would be hard to imagine a more winsome and helpful introduction to the Christian doctrine of Scripture than this. In an area that has been a minefield of controversy, Brad East writes with clarity yet without polemic, with ecumenical sympathy yet without failing to take a clear position on all the important and contested issues. Whatever your convictions about the Bible and how it should be read, you will benefit from this book.

And the formidable Matthew Levering:

What an exciting book! East's basic moves are recognizable: he carries forward and integrates elements of the doctrines of Scripture of Webster, Boersma, and Jenson. This would be accomplishment enough for a normal book, but East is even bolder ecumenically than the masters upon whom he builds. Without ceasing to value the Reformers, he challenges sola scriptura and the perspicacity of Scripture, and he offers a deeply Catholic account of dogma and apostolicity. This book is a rare gift—a richly comprehensive theology of Scripture that lays the foundation for real ecumenical breakthroughs.

And Darren Sarisky, a once rising star who now is unquestionably one of the leading lights in Christian theology of Scripture:

Brad East writes about the Bible with joy, verve, and insight. His presentation is highly readable, opening the subject up to all those who want to explore a theological perspective on Scripture. His strategy of working from church practice back to the nature and qualities of the text gives us all much to ponder.

And last but not least, Steve Fowl, whom I sometimes affectionately call the pope of the discipline (in his case, theological interpretation of Scripture):

Brad East's The Doctrine of Scripture raises all the key issues for theologians and biblical scholars to think about with regard to the nature and place of Scripture in a Christian theological framework. In a lucid and highly accessible style, he makes a compelling case for why these issues matter for theology and Scriptural interpretation.

When I read those names and their comments, and when that evil demon Imposter isn’t haunting my addled brain, I think, after pinching myself, that maybe I did something right. Or at least wrong in interesting ways. In either case, you should pick up a copy for yourself!

Speaking of which: I’ve buried the lede. You may want to purchase the book from Amazon or some other typical online outlet, but if you buy it from the publisher’s website, you can use the coupon code EASTBK2 to get 40% off the listed price (currently $28). Come on, y’all! You can spare an extra $20 bill for a book that sings, can’t you?

Here, by the way, is a description of the book’s contents:

When Holy Scripture is read aloud in the liturgy, the church confesses with joy and thanksgiving that it has heard the word of the Lord. What does it mean to make that confession? And why does it occasion praise? The doctrine of Scripture is a theological investigation into those and related questions, and this book is an exploration of that doctrine. It argues backward from the church’s liturgical practice, presupposing the truth of the Christian confession: namely, that the canon does in fact mediate the living word of the risen Christ to and for his people. What must be true of the sacred texts of Old and New Testament alike for such confession, and the practices of worship in which it is embedded, to be warranted?

By way of an answer, the book examines six aspects of the doctrine of Scripture: its source, nature, attributes, ends, interpretation, and authority. The result is a catholic and ecumenical presentation of the historic understanding of the Bible common to the people of God across the centuries, an understanding rooted in the church’s sacred tradition, in service to the gospel, and redounding to the glory of the triune God.

Head over to my page dedicated to the book here on the website for further information; I’ll be updating it with links, excerpts, and reviews in the coming weeks, months, and years.

I conceived the idea for this book in the summer of 2018; I drafted it, start to finish, in the fall semester of 2019; I revised it in May/June of 2020, then put the finishing touches on it last December. The copyedits came in May earlier this year, then the proofs a month later, then the physical book a couple months after that. That’s by comparison to my next book, which comes out in April, whose creation will have encompassed a full decade by the time of its publication. (It’s a former dissertation: enough said.)

All that to say: This has been an incredibly fast process, and so it’s somewhat surreal to see the physical book in my hands more or less two years to the day after I began writing it. I’m extremely proud of what I’ve written. I can’t speak to the quality, but I can tell you that it’s my best work. If I have anything whatsoever to say on this topic—if I have any skill in writing or in theological thinking—then you’ll find it on display in this book. I hope you’ll give it a chance. I hope people find it useful, thought-provoking, persuasive, invigorating. But most of all I hope it serves Christ’s church, whose sacred book is my book’s subject matter. That book is Christ’s book, and if my little book leads anyone to understanding or reading or loving it more, or more deeply, then I will be satisfied, and then some.

But right now I’m all gratitude, from top to bottom. So thanks in advance to you, too, if you end up giving it your time.

Sound familiar?

Although he was often called a fascist and compared to Hitler, the parallel applied only to his methods. Not only was the historical situation hopeless for a radical change like fascism, the country being unprecedentedly prosperous, but McCarthy never showed any interest in reshaping society. Half confidence man, half ward politician, he was simply out for his own power and profit, and he took advantage of the nervousness about communism to gain these modest perquisites.

The puzzling thing about [Joseph] McCarthy was that he had no ideology, no program, not even any prejudices. He was not anti-labor, anti-Negro, anti-Semitic, anti-Wall Street, or anti-Catholic, to name the phobias most exploited by previous demagogues. He never went in for patriotic spellbinding, or indeed for oratory at all, his style being low-keyed and legalistic. Although he was often called a fascist and compared to Hitler, the parallel applied only to his methods. Not only was the historical situation hopeless for a radical change like fascism, the country being unprecedentedly prosperous, but McCarthy never showed any interest in reshaping society. Half confidence man, half ward politician, he was simply out for his own power and profit, and he took advantage of the nervousness about communism to gain these modest perquisites. The same opportunism which made him dangerous in a small way prevented him from being a more serious threat, since for such large historical operations as the subversion of a social order there is required—as the examples of Lenin and Hitler showed—a fanaticism which doesn’t shrink from commitment to programs which are often inopportune.

The contrast in demagogic styles between Hitler and McCarthy is related to national traits—and foibles. Hitler exploited the German weakness for theory, for vast perspectives of world history, for extremely large and excessively general ideas; McCarthy flourished on the opposite weakness in Americans, their respect for the Facts. A Hitler speech began: “The revolution of the twentieth century will purge the Jewish taint from the cultural bloodstream of Europe!” A McCarthy speech began: “I hold in my hand a letter dated…” He was a district attorney, not a messiah.

Each of the bold forays which put the Wisconsin condottiere on the front pages between 1949 and 1954 began with factual charges and collapsed when the facts did: the long guerilla campaign against the State Department; the denunciation of General Marshall as a traitor working for the Kremlin (set forth in a 60,000 word speech in the Senate, bursting with Facts, none of them relevant to the charge); the Voice of America circus; the Lattimore fiasco; and the final suicidal Pickett’s charge against the Army and the President. That the letter dated such-and-such almost always turned out to have slight connection with the point he was making (on one occasion it was a blank sheet of paper), that the Facts about the Communist conspiracy he presented with such drama invariably proved to be, at best, irrelevant and, at worst, simple lies—this cramped McCarthy’s style very little. He had working for him our fact-fetishism, which means in practice that a boldly asserted lie or half-truth has the same effect on our minds as if it were true, since few of us have the knowledge, the critical faculties or even the mere time to discriminate between fact and fantasy.

Furthermore, our press, in its typical American effort to avoid “editorializing”—that is, evaluating the news, or The Facts, in terms of some general criterion—considers any dramatic statement by a prominent person to be important “news” and, by journalistic reflex, puts it on the front page. (If it later turns out that the original Fact was untrue, this new Fact is also duly recorded, but on an inside page, so that the correction never has the force of the original non-Fact. Such are the complications of “just giving the news” without any un-American generalizing or evaluating; in real life, unfortunately, almost nothing is simple, not even The Facts.) A classic instance was the front-paging, several years ago, of a series of charges against Governor Warren of California, who was up before the Senate for confirmation as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. The charges were serious indeed, but the following day they were exposed as the fabrications of a recent inmate of a mental hospital; despite their prima facie absurdity, they had been automatically treated as major news because the notoriously irresponsible Senator Langer had given them to the press over his name.

In the case of McCarthy, the tragicomic situation prevailed for years that although The New York Times and most of the country’s other influential newspapers were editorially opposed to him, they played his game and, in the sacred name of reporting The Facts, gave him the front-page publicity on which his power fattened. (Thus when he “investigated” the scientists at Fort Monmouth, the Times solemnly printed his charges day after day on page one, and then, some weeks later, printed a series of feature articles of its own, demonstrating that the charges were without substance; a little checking in the first place might have evaluated the Monmouth “investigation” more realistically and relegated it to an inside page; but this, of course, would have been “editorializing.”) When McCarthy’s charisma evaporated after the TV public had had a chance to see him in action during the army hearings and after the Watkins Committee had reported unfavorably on his senatorial conduct, the press began running his exposés on the inside pages and he disappeared like a comic-opera Mephisto dropping through a trap door.

—Dwight Macdonald, “The Triumph of the Fact” (1957)—originally published in Anchor Review, later collected in Masscult and Midcult: Essays Against the American Grain

Welcome to the new blog, same as the old blog

Welcome, all! This is the new and permanent home of my blog, Resident Theologian, which used to be hosted at Blogspot. All the old posts have been imported here, and while I don’t anticipate deleting the old blog anytime soon, I may well do so at some point.

Welcome, all! This is the new and permanent home of my blog, Resident Theologian, which used to be hosted at Blogspot. All the old posts have been imported here, and while I don’t anticipate deleting the old blog anytime soon, I may well do so at some point.

There’s not much to offer by way of orientation: here’s the blog, same as the old, only housed on my personal site. If you want to know more about me, click the About tab above; if you want to know more about this blog, click the About the Blog link just below the blog title on the blog home page (how many times can I say “blog” in one sentence?).

What with the move, I’m hoping to ramp up my so-called mezzo-blogging this summer, perhaps as soon as next week. So stay tuned for that, and in any case, thanks for reading.

Addendum: If you are receiving this post via email, then you either signed up to do so on the Home page, or were already signed up to receive posts via email from the old blog. If there has been an error, or you no longer want to receive these posts in your inbox, just click “Unsubscribe” below, and you’ll be taken off the email list automatically (and permanently). Thanks for your patience as I navigate moving the blog from its old environs to these lovely new digs.

On blissful ignorance of Twitter trends, controversies, beefs, and general goings-on

When you're on Twitter, you notice what is "trending." This micro-targeted algorithmic function shapes your experience of the website, the news, the culture, and the world. Even if it were simply a reflection of what people were tweeting about the most, it would still be random, passing, and mass-generated. Who cares what is trending at any one moment?

More important, based on the accounts one follows, there is always some tempest in a teacup brewing somewhere or other. A controversy, an argument, a flame war, a personal beef: whatever its nature, the brouhaha exerts a kind of gravitational pull, sucking us poor online plebs into its orbit. And because Twitter is the id unvarnished, the kerfuffle in question is usually nasty, brutish, and unedifying. Worst of all, this tiny little momentary conflict warps one's mind, as if anyone cares except the smallest of online sub-sub-sub-sub-sub-sub-sub-"communities." For writers, journalists and academics above all, these Twitter battles start to take up residence in the skull, as if they were not only real but vital and important. Articles and essays are written about them; sometimes they are deployed (with earnest soberness) as a synecdoche for cultural skirmishes to which they bear only the most tangential, and certainly no causal, relationship.

As it turns out, when you are ignorant of such things, they cease in any way to weigh down one's mind, because they might as well not have happened. (If a tweet is dunked on but no one sees it, did the dunking really occur?) And this is all to the good, because 99.9% of the time, what happens on Twitter (a) stays on Twitter and (b) has no consequences—at least for us ordinary folks—in the real world. Naturally, I'm excluding e.g. tweets by the President or e.g. tweets that will get one fired. (Though those examples are just more reasons not to be on Twitter: I suppose if all such reasons were written down even the whole world would not have room for the books that would be written.) What I mean is: The kind of seemingly intellectually interesting tweet-threads and Twitter-arguments are almost never (possibly never-never) worth attending to in the moment.

Why? First, because they're usually stillborn: best not to have read them in the first place; there is always a better use of one's time. Second, because, although they feel like they are setting the terms of this or that debate, they are typically divorced from said debate, or merely symptoms of it, or just reflections of it: but in most cases, not where the real action is happening. Third, because if they're interesting enough—possibly even debate-setting enough—their author will publish them in an article or suchlike that will render redundant the original source of the haphazard thoughts that are now well organized and digestible in an orderly sequence of thought. Fourth and finally, because if a tweet or thread is significant enough (this is the .01% leftover from above), someone will publish about it and make known to the rest of us why it is (or, as the case may be, is actually not) important. In this last case, there is a minor justification for journalists not to delete their Twitter accounts; though the reasons for deletion are still strong, they can justify their use of the evil website (or at least spending time on it: one can read tweets without an account). For the rest of us, we can find out what happened on the hellscape that is Twitter in the same way we get the rest of our news: from reputable, established outlets. And not by what's trending at any one moment.

For writers and academics, the resulting rewards are incomparable. The time-honored and irrefutable wisdom not to read one's mentions—corrupting the mind, as it does, and sabotaging good writing—turns out to have broader application. Don't just avoid reading your mentions. Don't have mentions to read in the first place.

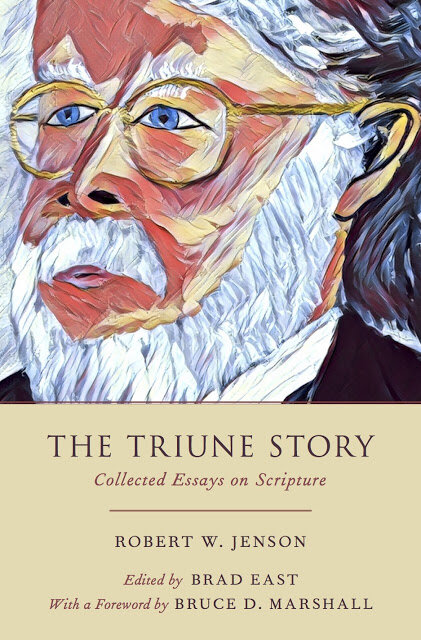

Pre-order The Triune Story today!

Oxford says the book will be out mid-June; Amazon says mid-July. I'd go with Amazon on that one. I'm working on indexing the book right now, after which point, late this month, I'll get the proofs. So perhaps the revised proofs will be ready by May 1? I don't know how quickly the turnaround is on these kinds of books, but perhaps quicker than I imagined. We also need to get the blurbs, about which more soon.

But, anyway, I only just happened upon this bit of news, and I couldn't be more delighted. This volume is going to be a real resource going forward, for Jenson scholars as well as for theologians interested in Scripture more broadly. I can't wait for y'all to have it in your hands.

And speaking of which, pre-order today! And how could you not, gazing on that gorgeous cover (image by the great Chris Green):

The value of keeping up with the news

"On Tuesday morning, January 22, I read a David Brooks column about a confrontation that happened on the National Mall during the March for Life. Until I read that column I had heard nothing about this incident because I do not have a Facebook account, have deleted my Twitter account, don’t watch TV news, and read the news about once a week. If all goes well, I won’t hear anything more about the story. I recommend this set of practices to you all."

This got me thinking about a post Paul Griffiths wrote on his blog years ago, perhaps even a decade ago (would that he kept that blog up longer!). He reflected on the ideal way of keeping up with the news—and, note well, this was before the rise of Twitter et al. as the driver of minute-by-minute "news" content. He suggested that there is no real good served in knowing what is going on day-to-day, whether that comes through the newspaper or the television. Instead, what one ought to do is slow the arrival of news to oneself so far as possible. His off-the-cuff proposal: subscribe to a handful of monthly or bimonthly publications ranging the ideological spectrum and, preferably, with a more global focus so as to avoid the parochialism not just of time but of space. Whenever the magazines or journals arrive, you devote a few hours to reading patient, time-cushioned reflection and reporting on the goings-on of the world—99% of which bears on your life not one iota—and then you continue on with your life (since, as should be self-evident to all of us, no one but a few family and friends needs to know what we think about it).

Consider how much saner your life, indeed all of our lives, would be if we did something like Griffiths' proposal. And think about how not doing it, and instead "engaging in the discourse," posting on Facebook, tweeting opinions, arguing online: how none of it does anything at all except raise blood pressure, foment discord, engender discontent, etc. Activists and advocates of local participatory democracy are fools if they think anything remotely like what we have now serves their goals. If we slowed our news intake, resisted the urge to pontificate, and paid more attention to the persons and needs and tasks before us, the world—as a whole and each of its parts—would be a much better place than it is at this moment.

Happy news: I'm editing a collection of Jenson's writings on Scripture

My thanks to Cynthia Read and to the editorial team at Oxford for supporting this book. Before his passing earlier this fall, Jens gave the project his blessing, and I hope it is a testament to the beauty and abiding value of his work both for the church and for the theological academy.

My hope is to have the book published by the end of next year, though that obviously depends on many forces outside my control. Perhaps even in time for a session at AAR/SBL...?

In any case, this has been an idea in the back of my mind for a few years now, and it's a joy to see it become a (proleptic) reality. Now y'all just be sure to buy it when it comes out.