Resident Theologian

About the Blog

Marilynne Robinson should know better

Like most seminary graduates and all theologians, I have long loved Marilynne Robinson. I read Gilead in the summer of 2005 and The Death of Adam shortly thereafter, and the deep affection created in those encounters has never left me. I have heard her speak on more than one occasion—at a church of Christ university and at Yale Divinity School, my two worlds colliding—and she was nothing but gracious, eloquent, and compelling in her anointed role as liberal Christian public intellectual. God give us more Marilynne Robinsons.

The beauty of her writing, her thought, and her public presence makes all the more painful the increasingly evident internal contradiction at the heart of her work. Others, with greater depth and insight than I am capable of offering here, have drawn attention to a related set of issues; see especially the reviews of her most recent volume of essays by Micah Meadowcroft, James K. A. Smith, B. D. McClay, Doug Sikkema, and Wesley Hill (alongside the earlier critique of Alan Jacobs, and the brief reflection yesterday by Bryan McGraw). The specific issue I am thinking of is not her inattention to original sin or total depravity, or the way in which such a lacuna is a serious misrepresentation of the Reformed tradition; or the way in which her politics is more or less a down-the-line box-checking of the Democratic National Committee, plus God and minus chronological snobbery; or how her public friendship with Barack Obama veers weirdly toward the obeisant—as if the former President did not order hundreds of drone strikes or deport millions of illegal immigrants or grant legal immunity to members of the CIA who engaged in torture under the previous administration or...

These and other matters are all worthy of interrogation and critique. What I'm interested in is her fundamental lack of charity or empathy toward people with whom she disagrees, namely red-state Christians, particularly those who voted for or continue to support Donald Trump.

Robinson is a novelist. The novelist's modus operandi is to create and embody the lives of human beings from the inside, human beings who are by definition not the author, whose beliefs and deeds are neither necessarily good nor necessarily defensible nor even necessarily consistent with one another. Moreover, Robinson has taken this deep attention to difference in the irreducible diversity of human affairs and applied it to history, recommending to others that they resist the thought-terminating prejudices of common cliche and instead offer to historically disreputable groups and personages the same benefit of doubt they would hope to be given themselves. Moses and Paul, Calvin and Cromwell, the Lollards and the Puritans: all are set within their original social and cultural context, judged by standards available at the time, compared to peers rather than progeny, permitted above all to be complex, conscientious, fallible, fallen, gloriously human members of one and the same species as the rest of us.

Comes the question: Why not use this same hermeneutic on the Repugnant Cultural Other that is the Trump-voting red-state would-be evangelical Christian? For, to use Alan Jacobs's term, that is what such a person is for Robinson. Doubtless such a person, and such a group, deserve robust criticism. They need not be treated with either paternalism or condescension. Say what you think, and give reasons why those with whom you disagree are wrong.

But Robinson does not take even one proverbial second to imagine the motivations or emotions or experiences of such people, or to consider how they might have been formed, or to what extent, if at all, they might be legitimate, whatever they popular expression in national politics or cable news. She does not step into their shoes. She does not even appear to imagine that they have shoes to step in. They are shoeless ciphers, a caricature without flesh and blood. And so she can, without irony, slander them in an essay on slander and Fox News; or question their Christian identity while challenging their recourse to drawing lines around orthodoxy; or treat them as a monolithic bloc in paeans to individualism; or castigate them as a group without showing knowledge of literate representation of their views, while wringing her hands about reading primary texts and avoiding capitulation to popular prejudice. Is there any popular prejudice more culturally acceptable in 2018 than dismissing all Republicans south of the Mason-Dixon line as bigoted dummies feigning faith as cover for benighted tribalism?

I am neither an evangelical nor a Republican nor a Trump voter. But I've lived in Texas, Georgia, and Connecticut, in major urban areas as well as "Trump country," with extended family spread out across the South and friends distributed along the Acela corridor. Robinson embodies the smug disdain common to all right-thinking people for folks I've counted and continue to count as neighbors, elders, family members, and fellow believers. More than anyone, Robinson should know that disagreement and critique, however fierce, are not obstacles to love—to the considerate love that generates attention, subtlety, and fellow feeling, without thereby obviating difference or conflict.

She should know better. She owes us more.

The beauty of her writing, her thought, and her public presence makes all the more painful the increasingly evident internal contradiction at the heart of her work. Others, with greater depth and insight than I am capable of offering here, have drawn attention to a related set of issues; see especially the reviews of her most recent volume of essays by Micah Meadowcroft, James K. A. Smith, B. D. McClay, Doug Sikkema, and Wesley Hill (alongside the earlier critique of Alan Jacobs, and the brief reflection yesterday by Bryan McGraw). The specific issue I am thinking of is not her inattention to original sin or total depravity, or the way in which such a lacuna is a serious misrepresentation of the Reformed tradition; or the way in which her politics is more or less a down-the-line box-checking of the Democratic National Committee, plus God and minus chronological snobbery; or how her public friendship with Barack Obama veers weirdly toward the obeisant—as if the former President did not order hundreds of drone strikes or deport millions of illegal immigrants or grant legal immunity to members of the CIA who engaged in torture under the previous administration or...

These and other matters are all worthy of interrogation and critique. What I'm interested in is her fundamental lack of charity or empathy toward people with whom she disagrees, namely red-state Christians, particularly those who voted for or continue to support Donald Trump.

Robinson is a novelist. The novelist's modus operandi is to create and embody the lives of human beings from the inside, human beings who are by definition not the author, whose beliefs and deeds are neither necessarily good nor necessarily defensible nor even necessarily consistent with one another. Moreover, Robinson has taken this deep attention to difference in the irreducible diversity of human affairs and applied it to history, recommending to others that they resist the thought-terminating prejudices of common cliche and instead offer to historically disreputable groups and personages the same benefit of doubt they would hope to be given themselves. Moses and Paul, Calvin and Cromwell, the Lollards and the Puritans: all are set within their original social and cultural context, judged by standards available at the time, compared to peers rather than progeny, permitted above all to be complex, conscientious, fallible, fallen, gloriously human members of one and the same species as the rest of us.

Comes the question: Why not use this same hermeneutic on the Repugnant Cultural Other that is the Trump-voting red-state would-be evangelical Christian? For, to use Alan Jacobs's term, that is what such a person is for Robinson. Doubtless such a person, and such a group, deserve robust criticism. They need not be treated with either paternalism or condescension. Say what you think, and give reasons why those with whom you disagree are wrong.

But Robinson does not take even one proverbial second to imagine the motivations or emotions or experiences of such people, or to consider how they might have been formed, or to what extent, if at all, they might be legitimate, whatever they popular expression in national politics or cable news. She does not step into their shoes. She does not even appear to imagine that they have shoes to step in. They are shoeless ciphers, a caricature without flesh and blood. And so she can, without irony, slander them in an essay on slander and Fox News; or question their Christian identity while challenging their recourse to drawing lines around orthodoxy; or treat them as a monolithic bloc in paeans to individualism; or castigate them as a group without showing knowledge of literate representation of their views, while wringing her hands about reading primary texts and avoiding capitulation to popular prejudice. Is there any popular prejudice more culturally acceptable in 2018 than dismissing all Republicans south of the Mason-Dixon line as bigoted dummies feigning faith as cover for benighted tribalism?

I am neither an evangelical nor a Republican nor a Trump voter. But I've lived in Texas, Georgia, and Connecticut, in major urban areas as well as "Trump country," with extended family spread out across the South and friends distributed along the Acela corridor. Robinson embodies the smug disdain common to all right-thinking people for folks I've counted and continue to count as neighbors, elders, family members, and fellow believers. More than anyone, Robinson should know that disagreement and critique, however fierce, are not obstacles to love—to the considerate love that generates attention, subtlety, and fellow feeling, without thereby obviating difference or conflict.

She should know better. She owes us more.

Defining fundamentalism

What makes a fundamentalist? It seems to me that there are only two workable definitions, one historical and one a sort of substantive shorthand. The first refers to actual self-identified fundamentalists from the early and mid-twentieth centuries, and to their (similarly defined) heirs today. The second refers to those Christian individuals or groups who, as it is often said, "lack a hermeneutic," that is, do not admit that hermeneutics is both unavoidable and necessary, and that therefore their interpretation of the Bible is not the only possible one for any rational literate person (or believer).

In my experience, both in print and in conversation, these definitions are very rarely operative. Colloquially, "fundamentalist" often means simply "bad," "conservative," or "to the right of me." I take it for granted that this usage is unjustified and to be avoided by any Christian, scholarly or otherwise; it is not only imprecise, it is little more than tribal slander. "I'm on the good team, and since she disagrees with me, she must be on the bad team."

Is there a workable definition beyond the options so far canvassed? In my judgment, it can't mean "someone who does not accept the deliverances of historical criticism," because those deliverances are by definition disputed; you can always find a non-fundamentalist who happens to affirm a stereotypically designated "fundamentalist" position. Postmodern hermeneutics cuts out the ground from the "sure deliverances" of historical criticism anyway.

Nor can the term, in my view, be applied usefully or consistently to specific doctrinal positions: the inerrancy of Scripture; male headship; traditional sexuality; young earth creationism; a denial of humanity's evolutionary origins; etc. On the one hand, "fundamentalist" isn't helpful because it carries so much historical and other baggage, while these positions can simply be named with terminological specificity. On the other hand, there are extraordinarily sophisticated historical, philosophical, and theological arguments for each and every one of these positions that belie the pejorative, "dummy know-nothing" evocations of "fundamentalism." That doesn't mean all or any of them are correct; it just means that branding them with the F-word is an exercise in both ad hominem and straw man tactics. The term itself has ceased to do work other than the functional task of marking who's in and who's out.

Finally, the term cannot mean "people or positions that use or allow the claims of revelation to trump other claims to knowledge." I fail to see how the epistemic primacy of revelation could ever be a mark of fundamentalism without thereby consigning all of Christian tradition and most of the contemporary global church to fundamentalist oblivion. And, again, it would come to mean so much that it would therefore mean very little indeed. If (nearly) everyone's a fundamentalist, then that doesn't tell us anything of value about the Christians so labeled.

So: Anyone got a useful definition to proffer? For myself, I'll limit myself in theory to the first two definitions listed, while in practice refraining from using the term altogether.

In my experience, both in print and in conversation, these definitions are very rarely operative. Colloquially, "fundamentalist" often means simply "bad," "conservative," or "to the right of me." I take it for granted that this usage is unjustified and to be avoided by any Christian, scholarly or otherwise; it is not only imprecise, it is little more than tribal slander. "I'm on the good team, and since she disagrees with me, she must be on the bad team."

Is there a workable definition beyond the options so far canvassed? In my judgment, it can't mean "someone who does not accept the deliverances of historical criticism," because those deliverances are by definition disputed; you can always find a non-fundamentalist who happens to affirm a stereotypically designated "fundamentalist" position. Postmodern hermeneutics cuts out the ground from the "sure deliverances" of historical criticism anyway.

Nor can the term, in my view, be applied usefully or consistently to specific doctrinal positions: the inerrancy of Scripture; male headship; traditional sexuality; young earth creationism; a denial of humanity's evolutionary origins; etc. On the one hand, "fundamentalist" isn't helpful because it carries so much historical and other baggage, while these positions can simply be named with terminological specificity. On the other hand, there are extraordinarily sophisticated historical, philosophical, and theological arguments for each and every one of these positions that belie the pejorative, "dummy know-nothing" evocations of "fundamentalism." That doesn't mean all or any of them are correct; it just means that branding them with the F-word is an exercise in both ad hominem and straw man tactics. The term itself has ceased to do work other than the functional task of marking who's in and who's out.

Finally, the term cannot mean "people or positions that use or allow the claims of revelation to trump other claims to knowledge." I fail to see how the epistemic primacy of revelation could ever be a mark of fundamentalism without thereby consigning all of Christian tradition and most of the contemporary global church to fundamentalist oblivion. And, again, it would come to mean so much that it would therefore mean very little indeed. If (nearly) everyone's a fundamentalist, then that doesn't tell us anything of value about the Christians so labeled.

So: Anyone got a useful definition to proffer? For myself, I'll limit myself in theory to the first two definitions listed, while in practice refraining from using the term altogether.

The thing about Phantom Thread

is that it's one of three things, none satisfactory. Either:

1. It's a profound meditation on the nature of love, on something intrinsic to love between men and women, a kind of unavoidable, even beautiful, crack in the surface of what is usually presented as seamless, without defect: in which case the film is false, self-deluded, and self-serious. Or:

2. It's a cheeky close-up, not on love in general, but on this particular couple's "love," doomed to dysfunction, an eternal power-play, in which the would-be submissive learns how to gain the upper hand, and the otherwise dominant, now dominated, accepts this kink in the relationship with a wry ardor: in which case the film is vile, an unserious exercise in sadomasochism either metaphorized or taken to an absurd extreme. Or:

3. It's nothing more than funny (and it is very funny), using the trappings of prestige film and high fashion and world-class acting and audience expectations as a Trojan horse for avant garde melodrama, gender-role hijinks, and an all-around send-up of the infinitely humorless genre of Very Serious Genius Men And Their Long-Suffering Muses: in which case the film is a rousing success, but ultimately quite shallow; and its central plot device is such a severe misdirect that the film's biggest fans have mistaken it for that which it is meant to parody: a meaningful commentary on love, genius, gender, art, power, etc.

These are also the stages of my own judgment about the film. I can make no sense of people who opt for either of the first two interpretations and acclaim the movie's greatness. And if, as I have come to believe, the third interpretation is best, then Anderson accomplished a task that wasn't worth the time or energy of his genuine genius. Or at least, it's not worth any more of my time, which otherwise might have been devoted to rewatching and continuing to reflect on such a film.

C. S. Lewis on the fumie

Meanwhile, in the Objective Room, something like a crisis had developed between Mark and Professor Frost. As soon as they arrived there Mark saw that the table had been drawn back. On the floor lay a large crucifix, almost life size, a work of art in the Spanish tradition, ghastly and realistic.

“We have half an hour to pursue our exercises,” said Frost looking at his watch. Then he instructed Mark to trample on it and insult it in other ways.

Now whereas Jane had abandoned Christianity in early childhood, along with her belief in fairies and Santa Claus, Mark had never believed in it at all. At this moment, therefore, it crossed his mind for the very first time that there might conceivably be something in it. Frost who was watching him carefully knew perfectly well that this might be the result of the present experiment. He knew it for the very good reason that his own training by the Macrobes had, at one point, suggested the same odd idea to himself. But he had no choice. Whether he wished it or not this sort of thing was part of the initiation.

“But, look here," said Mark.

“What is it?" said Frost. “Pray be quick. We have only a limited time at our disposal.”

“This,” said Mark, pointing with an undefined reluctance to the horrible white figure on the cross. “This is all surely a pure superstition.”

“Well?”

“Well, if so, what is there objective about stamping on the face? Isn’t is just as subjective to spit on a thing like this as to worship it? I mean—damn it all—if it’s only a bit of wood, why do anything about it?”

“That is superficial. If you had been brought up in a non-Christian society, you would not be asked to do this. Of course, it is a superstition; but it is that particular superstition which has pressed upon our society for a great many centuries. It can be experimentally shown that is still forms a dominant system in the subconscious of many individuals whose conscious thought appears to be wholly liberated. An explicit action in the reverse direction is therefore a necessary step towards complete objectivity. It is not a question for a priori discussion. We find it in practice that it cannot be dispensed with.”

Mark himself was surprised at the emotions he was undergoing. He did not regard the image with anything at all like a religious feeling. Most emphatically it did not belong to that idea of the Straight or Normal or Wholesome which had, for the last few days, been his support against what he now knew of the innermost circle at Belbury. The horrible vigour of its realism was, indeed, in its own way as remote from that Idea as anything else in the room. That was one source of his reluctance. To insult even a carved image of such agony seemed an abominable act. But it was not the only source. With the introduction of this Christian symbol the whole situation had somehow altered. The thing was becoming incalculable. His simple antithesis of the Normal and the Diseased had obviously failed to take something into account. Why was the Crucifix there? Why were more than half of the poison-pictures religious? He had the sense of new parties to the conflict—potential allies and enemies which he had not suspected before. “If I take a step in any direction,” he thought, “I may step over a precipice.” A donkey like determination to plant hoofs and stay still at all costs arose in his mind.

“Pray make haste,” said Frost.

The quiet urgency of the voice, and the fact that he had so often obeyed it before, almost conquered him. He was on the verge of obeying, and getting the whole silly business over, when the defenselessness of the figure deterred him. the feeling was a very illogical one. Not because its hands were nailed and helpless, but because they were only made of wood and therefore even more helpless, because the thing, for all its realism, was inanimate and could not in any way hit back, he paused. The unretaliating face of a doll—one of Myrtle’s dolls—which he had pulled to pieces in boyhood had affected him in the same way and the memory, even now, was tender to the touch.

“What are you waiting for, Mr. Studdock?” said Frost.

Mark was well aware of the rising danger. Obviously, if he disobeyed, his last chance of getting out of Belbury alive might be gone. Even of getting out of this room. The smothering sensation once again attacked him. He was himself, he felt, as helpless as the wooden Christ. As he thought this, he found himself looking at the crucifix in a new way—neither as a piece of wood nor a monument of superstition but as a bit of history. Christianity was nonsense, but one did not doubt that the man had lived and had been executed thus by the Belbury of those days. And that, as he suddenly saw, explained why this image,though not itself an image of the Straight or Normal, was yet in opposition to the crooked Belbury. It was a picture of what happened when the Straight met the Crooked, a picture of what the Crooked did to the Straight—what it would do to him if he remained straight. It was, in a more emphatic sense than he had yet understood, a cross.

“Do you intend to go on with the training or not?” said Frost. His eye was on the time. . . .

“Do you not hear what I am saying?” he asked Mark again.

Mark made no reply. He was thinking, and thinking hard because he knew, that if he stopped even for a moment, mere terror of death would take the decision out of his hands. Christianity was a fable. It would be ridiculous to die for a religion one did not believe. This Man himself, on that very cross, had discovered it to be a fable, and had died complaining that the God in whom he trusted had forsaken him—had, in fact, found the universe a cheat. But this raised a question that Mark had never thought of before. Was that the moment at which to turn against the Man? If the universe was a cheat, was that a good reason for joining its side? Supposing the Straight was utterly powerless, always and everywhere certain to be mocked, tortured, and finally killed by the Crooked, what then? Why not go down with the ship? He began to be frightened by the very fact that his fears seemed to have momentarily vanished. They had been a safeguard . . . they had prevented him, all his life, from making mad decisions like that which he was now making as he turned to Frost and said,

“It’s all bloody nonsense, and I’m damned if I do any such thing.”

When he said this he had no idea what might happen next.

—C. S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength, pp. 334-337

Now whereas Jane had abandoned Christianity in early childhood, along with her belief in fairies and Santa Claus, Mark had never believed in it at all. At this moment, therefore, it crossed his mind for the very first time that there might conceivably be something in it. Frost who was watching him carefully knew perfectly well that this might be the result of the present experiment. He knew it for the very good reason that his own training by the Macrobes had, at one point, suggested the same odd idea to himself. But he had no choice. Whether he wished it or not this sort of thing was part of the initiation.

“But, look here," said Mark.

“What is it?" said Frost. “Pray be quick. We have only a limited time at our disposal.”

“This,” said Mark, pointing with an undefined reluctance to the horrible white figure on the cross. “This is all surely a pure superstition.”

“Well?”

“Well, if so, what is there objective about stamping on the face? Isn’t is just as subjective to spit on a thing like this as to worship it? I mean—damn it all—if it’s only a bit of wood, why do anything about it?”

“That is superficial. If you had been brought up in a non-Christian society, you would not be asked to do this. Of course, it is a superstition; but it is that particular superstition which has pressed upon our society for a great many centuries. It can be experimentally shown that is still forms a dominant system in the subconscious of many individuals whose conscious thought appears to be wholly liberated. An explicit action in the reverse direction is therefore a necessary step towards complete objectivity. It is not a question for a priori discussion. We find it in practice that it cannot be dispensed with.”

Mark himself was surprised at the emotions he was undergoing. He did not regard the image with anything at all like a religious feeling. Most emphatically it did not belong to that idea of the Straight or Normal or Wholesome which had, for the last few days, been his support against what he now knew of the innermost circle at Belbury. The horrible vigour of its realism was, indeed, in its own way as remote from that Idea as anything else in the room. That was one source of his reluctance. To insult even a carved image of such agony seemed an abominable act. But it was not the only source. With the introduction of this Christian symbol the whole situation had somehow altered. The thing was becoming incalculable. His simple antithesis of the Normal and the Diseased had obviously failed to take something into account. Why was the Crucifix there? Why were more than half of the poison-pictures religious? He had the sense of new parties to the conflict—potential allies and enemies which he had not suspected before. “If I take a step in any direction,” he thought, “I may step over a precipice.” A donkey like determination to plant hoofs and stay still at all costs arose in his mind.

“Pray make haste,” said Frost.

The quiet urgency of the voice, and the fact that he had so often obeyed it before, almost conquered him. He was on the verge of obeying, and getting the whole silly business over, when the defenselessness of the figure deterred him. the feeling was a very illogical one. Not because its hands were nailed and helpless, but because they were only made of wood and therefore even more helpless, because the thing, for all its realism, was inanimate and could not in any way hit back, he paused. The unretaliating face of a doll—one of Myrtle’s dolls—which he had pulled to pieces in boyhood had affected him in the same way and the memory, even now, was tender to the touch.

“What are you waiting for, Mr. Studdock?” said Frost.

Mark was well aware of the rising danger. Obviously, if he disobeyed, his last chance of getting out of Belbury alive might be gone. Even of getting out of this room. The smothering sensation once again attacked him. He was himself, he felt, as helpless as the wooden Christ. As he thought this, he found himself looking at the crucifix in a new way—neither as a piece of wood nor a monument of superstition but as a bit of history. Christianity was nonsense, but one did not doubt that the man had lived and had been executed thus by the Belbury of those days. And that, as he suddenly saw, explained why this image,though not itself an image of the Straight or Normal, was yet in opposition to the crooked Belbury. It was a picture of what happened when the Straight met the Crooked, a picture of what the Crooked did to the Straight—what it would do to him if he remained straight. It was, in a more emphatic sense than he had yet understood, a cross.

“Do you intend to go on with the training or not?” said Frost. His eye was on the time. . . .

“Do you not hear what I am saying?” he asked Mark again.

Mark made no reply. He was thinking, and thinking hard because he knew, that if he stopped even for a moment, mere terror of death would take the decision out of his hands. Christianity was a fable. It would be ridiculous to die for a religion one did not believe. This Man himself, on that very cross, had discovered it to be a fable, and had died complaining that the God in whom he trusted had forsaken him—had, in fact, found the universe a cheat. But this raised a question that Mark had never thought of before. Was that the moment at which to turn against the Man? If the universe was a cheat, was that a good reason for joining its side? Supposing the Straight was utterly powerless, always and everywhere certain to be mocked, tortured, and finally killed by the Crooked, what then? Why not go down with the ship? He began to be frightened by the very fact that his fears seemed to have momentarily vanished. They had been a safeguard . . . they had prevented him, all his life, from making mad decisions like that which he was now making as he turned to Frost and said,

“It’s all bloody nonsense, and I’m damned if I do any such thing.”

When he said this he had no idea what might happen next.

—C. S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength, pp. 334-337

Just published: a review essay of Patrick Deneen and James K. A. Smith in the LA Review of Books

I've got a review essay in the Los Angeles Review of Books of Patrick Deneen's Why Liberalism Failed and James K. A. Smith's Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology. It's called "Holy Ambivalence." Go check it out.

Principles of Luddite pedagogy

My classes begin in this way: With phone in hand, I say, "Please put your phones and devices away," and thereupon put my own in my bag out of sight. I then say, "The Lord be with you." (And also with you.) "Let us pray." I then offer a prayer, usually the Collect for the day from the Book of Common Prayer. After the prayer, we get started. And for the next 80 minutes (or longer, if it is a grad seminar or intensive course), there is not a laptop, tablet, or smart phone in sight. If I catch a student on her phone, and Lord knows college students are not subtle, she is counted tardy for the day and docked points on her participation grade. Only after I dismiss class do the addicts—sorry, my students—satiate their gnawing hunger for a screen, and get their fix.

For larger lecture courses (40-60 students) with lots of information to communicate, I use PowerPoint slides. But for smaller numbers and especially for seminars, neither a computer nor the internet nor a screen of any kind is employed during class time. I further require my students to submit their papers (however short or long, however rarely or commonly due) in the form of a printed copy brought to class or dropped off at my office. And for weekly (or random) reading quizzes, students must come prepared with pencil and Scantron; we begin the quiz promptly at the beginning of class, with the questions coming sequentially in large print on the PowerPoint slides. I give them plenty of time for each question, but I do not go back to previous questions. If you arrive late and miss questions or the whole thing, so be it.

I rarely reply immediately to emails, and may not reply at all if the question's answer is specified in the syllabus. I will reply within 24 hours, but I will not reply (unless it is an emergency) after hours, while at home; some days I may not even check my work email between 5:00pm and 6:00am the following morning.

I have a strict attendance policy: I count both tardies and absences; three of the former count as one of the latter; and beginning with three unexcused absences (for a twice-weekly course), I deduct four percentage points from a student's final grade. So, e.g., a student with four unexcused absences and three tardies would go from a 91 to a 79. More than six unexcused absences means an automatic failing grade.

Students behave exactly as you suppose they would. They come to class, they show up on time, they do the reading, and they take hand-written notes. The only distraction they fight is drowsiness (I will not say whether I contribute to that perennial pedagogical opponent). And for two 80-minute blocks of time per week, these students who were in second grade when the first iPhone came out have neither a device in their hands nor a screen before their eyes nor buds in their ears.

It turns out I am a Luddite, at least pedagogically speaking. On the questions raised by this set of issues, my sense is that my colleagues, not just at my university but in the academy generally, are divided into three campus. There are those like me. There are those who find us and our pedagogy desirable, but for reasons intrinsic or extrinsic to themselves they cannot or will not join us and fashion their classrooms accordingly. And then there are those who, on principle, oppose Luddite pedagogy.

This last group, broadly speaking, views screens, phones, tablets, laptops, the internet, etc., as positive supplements or complements to the traditional teaching setting, and want as far as possible to incorporate student use of them in the classroom. This view extends beyond the classroom to, e.g., learning management systems and e-books, videos and podcasts, etc., etc. The scope of the classroom expands to include the digital architecture of LMS: a "space" online where discussion, assignments, interaction, learning, video, editing, grading feedback, and so on are consolidated and intertwined.

What rationale underwrites this perspective? Perhaps it is simply "where we are today," or "what we have to do" in the 21st century, working with digital-native millennials; or perhaps it is neither superior nor inferior to traditional classroom learning, but simply a different mode of teaching altogether, with its own strengths and weaknesses; or perhaps it is not sufficient but certainly necessary alongside the classroom, given its many ostensible benefits; or perhaps it is both necessary and sufficient, superior to because an improvement upon the now defunct pedagogical elements of old: a room, some desks, a teacher and students, some books, a board, paper and pencil.

I'm not going to make an argument against these folks. I think they're wrong, but that's for another day. Rather, I want to think about the basic principles underlying my own not-always-theorized pedagogical Ludditism—a stance I did not plan to take but found myself taking with ever greater commitment, confidence, and articulateness. What might those principles be?

Here's a first stab.

1. I want, insofar as possible, to interrupt and de-normalize the omnipresence of screens in my students' lives.

2. I want, insofar as possible, to get my students off the internet.

3. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to hold physical books in their hands, to turn pages, to read words off a page, to annotate what they read with pen or pencil.

4. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to put pen or pencil to paper, to write out their thoughts, reflections, answers, and arguments in longhand.

5. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to develop habits of silent, contemplative thought: the passive activity of the mind, lacking external stimulation, lost in a world known only to themselves—though by definition intrinsically communicable to others—chasing down stray thoughts and memories down back alleys in the brain.

6. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to practice talking out loud to their neighbors, friends, and strangers about matters of great import, sustained for minutes or even hours at a time, without the interposition or upward-facing promise of the smart phone's rectangle of light; to learn and develop habits of sustained discourse, even and especially to the point of disagreement, offering and asking for reasons that support one or another position or perspective, without recourse to some less demanding activity, much less to the reflexive conversation-stopper of personal offense.

7. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to see that the world to which they have grown accustomed, whose habits and assumptions they have imbibed and intuited without critique, consent, or forethought, is contingent: it is neither necessary nor necessarily good; that even in this world, resistance is possible; indeed, that the very intellectual habits on display in the classroom are themselves a form of and a pathway to a lifetime of such resistance.

8. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to experience, in their gut, as a kind of assault on their unspoken assumptions, that the life of the mind is at once more interesting than they imagined, more demanding than a simple passing grade (not to mention a swipe to the left or the right), and more rewarding than the endless mindless numbing pursuits of their screens.

9. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to realize that they are not the center of the universe, and certainly not my universe; that I am not waiting on them hand and foot, their digital butler, ready to reply to the most inconsequential of emails at a moment's notice; that such a way of living, with the notifications on red alert at all times of the day, even through the night, is categorically unhealthy, even insane.

In sum, I want the pedagogy that informs my classroom to be a sustained embodiment of Philip's response to Nathaniel's challenge in the Gospel of John. Can anything good come from a classroom without devices, from teaching and learning freed from technology's imperious determination?

Come and see.

For larger lecture courses (40-60 students) with lots of information to communicate, I use PowerPoint slides. But for smaller numbers and especially for seminars, neither a computer nor the internet nor a screen of any kind is employed during class time. I further require my students to submit their papers (however short or long, however rarely or commonly due) in the form of a printed copy brought to class or dropped off at my office. And for weekly (or random) reading quizzes, students must come prepared with pencil and Scantron; we begin the quiz promptly at the beginning of class, with the questions coming sequentially in large print on the PowerPoint slides. I give them plenty of time for each question, but I do not go back to previous questions. If you arrive late and miss questions or the whole thing, so be it.

I rarely reply immediately to emails, and may not reply at all if the question's answer is specified in the syllabus. I will reply within 24 hours, but I will not reply (unless it is an emergency) after hours, while at home; some days I may not even check my work email between 5:00pm and 6:00am the following morning.

I have a strict attendance policy: I count both tardies and absences; three of the former count as one of the latter; and beginning with three unexcused absences (for a twice-weekly course), I deduct four percentage points from a student's final grade. So, e.g., a student with four unexcused absences and three tardies would go from a 91 to a 79. More than six unexcused absences means an automatic failing grade.

Students behave exactly as you suppose they would. They come to class, they show up on time, they do the reading, and they take hand-written notes. The only distraction they fight is drowsiness (I will not say whether I contribute to that perennial pedagogical opponent). And for two 80-minute blocks of time per week, these students who were in second grade when the first iPhone came out have neither a device in their hands nor a screen before their eyes nor buds in their ears.

It turns out I am a Luddite, at least pedagogically speaking. On the questions raised by this set of issues, my sense is that my colleagues, not just at my university but in the academy generally, are divided into three campus. There are those like me. There are those who find us and our pedagogy desirable, but for reasons intrinsic or extrinsic to themselves they cannot or will not join us and fashion their classrooms accordingly. And then there are those who, on principle, oppose Luddite pedagogy.

This last group, broadly speaking, views screens, phones, tablets, laptops, the internet, etc., as positive supplements or complements to the traditional teaching setting, and want as far as possible to incorporate student use of them in the classroom. This view extends beyond the classroom to, e.g., learning management systems and e-books, videos and podcasts, etc., etc. The scope of the classroom expands to include the digital architecture of LMS: a "space" online where discussion, assignments, interaction, learning, video, editing, grading feedback, and so on are consolidated and intertwined.

What rationale underwrites this perspective? Perhaps it is simply "where we are today," or "what we have to do" in the 21st century, working with digital-native millennials; or perhaps it is neither superior nor inferior to traditional classroom learning, but simply a different mode of teaching altogether, with its own strengths and weaknesses; or perhaps it is not sufficient but certainly necessary alongside the classroom, given its many ostensible benefits; or perhaps it is both necessary and sufficient, superior to because an improvement upon the now defunct pedagogical elements of old: a room, some desks, a teacher and students, some books, a board, paper and pencil.

I'm not going to make an argument against these folks. I think they're wrong, but that's for another day. Rather, I want to think about the basic principles underlying my own not-always-theorized pedagogical Ludditism—a stance I did not plan to take but found myself taking with ever greater commitment, confidence, and articulateness. What might those principles be?

Here's a first stab.

1. I want, insofar as possible, to interrupt and de-normalize the omnipresence of screens in my students' lives.

2. I want, insofar as possible, to get my students off the internet.

3. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to hold physical books in their hands, to turn pages, to read words off a page, to annotate what they read with pen or pencil.

4. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to put pen or pencil to paper, to write out their thoughts, reflections, answers, and arguments in longhand.

5. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to develop habits of silent, contemplative thought: the passive activity of the mind, lacking external stimulation, lost in a world known only to themselves—though by definition intrinsically communicable to others—chasing down stray thoughts and memories down back alleys in the brain.

6. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to practice talking out loud to their neighbors, friends, and strangers about matters of great import, sustained for minutes or even hours at a time, without the interposition or upward-facing promise of the smart phone's rectangle of light; to learn and develop habits of sustained discourse, even and especially to the point of disagreement, offering and asking for reasons that support one or another position or perspective, without recourse to some less demanding activity, much less to the reflexive conversation-stopper of personal offense.

7. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to see that the world to which they have grown accustomed, whose habits and assumptions they have imbibed and intuited without critique, consent, or forethought, is contingent: it is neither necessary nor necessarily good; that even in this world, resistance is possible; indeed, that the very intellectual habits on display in the classroom are themselves a form of and a pathway to a lifetime of such resistance.

8. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to experience, in their gut, as a kind of assault on their unspoken assumptions, that the life of the mind is at once more interesting than they imagined, more demanding than a simple passing grade (not to mention a swipe to the left or the right), and more rewarding than the endless mindless numbing pursuits of their screens.

9. I want, insofar as possible, for my students to realize that they are not the center of the universe, and certainly not my universe; that I am not waiting on them hand and foot, their digital butler, ready to reply to the most inconsequential of emails at a moment's notice; that such a way of living, with the notifications on red alert at all times of the day, even through the night, is categorically unhealthy, even insane.

In sum, I want the pedagogy that informs my classroom to be a sustained embodiment of Philip's response to Nathaniel's challenge in the Gospel of John. Can anything good come from a classroom without devices, from teaching and learning freed from technology's imperious determination?

Come and see.

Rowan Williams on Jewish identity and religious freedom in liberal modernity

"The [French] revolution wanted to save Jews from Judaism, turning them into

rational citizens untroubled by strange ancestral superstitions. It

ended up taking just as persecutory an approach as the Church and the

Christian monarchy. The legacies of Christian bigotry and enlightened

contempt are tightly woven together in the European psyche, it seems,

and the nightmares of the 20th century are indebted to both strands.

"In some ways, this prompts the most significant question to emerge from

the [history of Jews in modern Europe]. Judaism

becomes a stark test case for what we mean by pluralism and religious

liberty: if the condition for granting religious liberty is, in effect,

conformity to secular public norms, what kind of liberty is this? More

than even other mainstream religious communities, Jews take their stand

on the fact that their identity is not an optional leisure activity or

lifestyle choice. Their belief is that they are who they are for reasons

inaccessible to the secular state, and they ask that this particularity

be respected—granted that it will not interfere with their compliance

with the law of the state.

"This question is currently a pressing one. Does liberal modernity mean

the eradication of organic traditions and identities, communal belief

and ritual, in the name of absolute public uniformity? Or does it

involve the harder work of managing the reality that people have diverse

religious and cultural identities as well as their papers of

citizenship, and accepting that these identities will shape the way they

interact?

"Yet again, we see how Jews can be caught in a mesh of skewed

perception. The argumentative dice are loaded against them. As a

distinctive cluster of communities held together by language, history

and law—with the assumption for the orthodox believer that all of this

is the gift of God—they pose a threat to triumphalist religious

systems that look to universal hegemony and conversion.

"The Christian or Muslim zealot cannot readily accept the claim of an

identity that is simply given and not to be argued away by the doctrines

of newer faiths. But the dogmatic secularist finds this no easier.

Liberation from confessional and religiously exclusive societies ought,

they think, to mean the embrace of a uniform enlightened world-view—but the Jew continues to insist that particularity is not negotiable. So

we see the grimly familiar picture emerging of Judaism as the target of

both left and right.

"The importance of [this history] is that it forces the reader to think

about how the long and shameful legacy of Christian hatred for Jews is

reworked in 'enlightened' society. Jews are just as 'other' for a

certain sort of progressive politics and ethics as they were for early

and medieval Christianity. The offence is the sheer persistence of an

identity that refuses to understand itself as just a minor variant of

the universal human culture towards which history is meant to be

working. And to understand how this impasse operated is to understand

something of why Zionism gains traction long before the Holocaust."

My dissertation acknowledgements

Dissertations are strange creatures: written by many, read by few, important to none but the authors. In a way, dissertations are like the angels of St. Thomas Aquinas, not species of a genus but each a genus unto itself.

And yet many years, blood, sweat, and tears go into dissertations; and so the acknowledgements at their beginning are often a moment to step back and thank those who have made finishing the (by then) cursed thing possible. So far as I can tell, there are two different types of acknowledgements: minimalist and maximalist. Either the author thanks only those who contributed materially and directly to the dissertation's production (one friend thanked, if I recall correctly, only about a dozen individuals), or she mentions more or less every single human being she has met along the way—anyone from whom she has received as much as a cup of cold water. I fall in the latter category, both by temperament (being prolix in life and in prose) and by conviction (a lot of people helped me get to the point of completing this thing!).

But because one is lucky if the readership of one's dissertation exceeds single digits, the writing of acknowledgements can seem somewhat narcissistic, or at least futile. Wherefore I have opted to share my acknowledgements here on the blog. Though I completed and submitted the manuscript last May, it wasn't approved until October and I didn't officially graduate until December. So the proverbial ink has yet to dry, and while it does so, let me share with y'all the many names and institutions and communities—each and every one—that made possible, by God's grace, my earning a PhD in theology from Yale University in the Year of Our Lord 2017.

Acknowledgements

It was Thanksgiving 2011, in a living room in Starkville, Mississippi, that the idea for this dissertation came to me. ‘Came to me’ is the right phrase: the idea was not mine, but my brother Garrett’s. He, my brother Mitch, and I were killing time in between meals, talking theology as brothers do. And Garrett said, “You know, you’ve been talking about this Webster a lot lately, and before that it was Jenson, and before that it was Yoder. Maybe you should write your dissertation on their theologies of Scripture.” Five and a half years later, here we are. So my first word of thanks goes to Garrett for giving me the idea for this project, to my sister-in-law Stacy for her relaxed toleration of our weakness for the rabies theologorum, and to Garrett and Mitch together for serving as soundboards, sparring partners, and friends throughout this process—and at all other times.

Thanks to my advisor, Kathryn Tanner, for constant encouragement, support, help (not least in saving me from featuring a fourth primary figure!), availability, theological wisdom, practical insight, and (what is not native to me) love of concision and economy of prose.

Thanks to the rest of the committee: Miroslav Volf, David Kelsey, and Steve Fowl. I could not have dreamed of a more fitting, or a more formidable, group of readers for a dissertation on this topic (they wrote the books on it, after all), and their kindness, generosity, and feedback have meant a great deal.

Thanks to the other faculty members from whom I learned or with whom I worked during my time at Yale: Christopher Beeley, John Hare, Linn Tonstad, Jennifer Herdt, Denys Turner, Dale Martin, Adam Eitel. If I have learned anything during my studies, I learned it primarily by osmosis from these brilliant, friendly scholars.

Thanks to my fellow students, in the Theology cohort and in other sub- disciplines: Awet Andemicael, Liza Anderson, Laura Carlson, Justin Crisp, Ryan Darr, TJ Dumansky, Jamie Dunn, Matt Fisher, Andrew Forsyth, Janna Gonwa, Justin Hawkins, Liv Stewart Lester, Mark Lester, Samuel Loncar, Wendy Mallette, Natalia Marandiuc, Sam Martinez, Ryan McAnnally-Linz, Ross McCullough, Luke Moorhead, Stephen Ogden, Devin Singh, Erinn Staley, John Stern, Graedon Zorzi. When I rave about the program at Yale, I am raving about these people.

Thanks to other friends, teachers, and colleagues, near and far, who were a part of my academic journey. In Abilene: Randy Harris, Tracy Shilcutt, Jeanene Reese, Wendell Willis, Glenn Pemberton, Josh Love, Reid Overall. In Atlanta: Ian McFarland, Luke Timothy Johnson, Steffen Lösel, Ellen Ott Marshall, Carol Newsom, Tim Jackson, Mark Lackowski, Leonard Wills, Don McLaughlin, Patrick and Karen Gosnell, Jimmy and Desiree McCarty, Matt and Stephanie Vyverberg, Seth and Kaci Borin, Daron and Margaret Dickens, Adam and Susan Paa. And elsewhere: Junius Johnson, Ben Langford, Andrew and Lindsey Krinks, David Fleer, Lauren Smelser White, David Mahfood, Fred Aquino, and Tyler Richards.

Thanks to the Christian Scholarship Foundation, from which I received a financial lifeline two years in a row, and to Carl Holladay and Greg Sterling, who oversee it.

Thanks to the Louisville Institute, from which I received a generous 2-year doctoral fellowship, and to the new friends and colleagues I made there: Ed Aponte, Don Richter, Terry Muck, Pam Collins, Kathleen O’Connor, Aaron Griffith, Kyle Lambelet, Amanda Pittman, Leah Payne, Derek Woodard-Lehman, Tim Snyder, Lorraine Cuddeback, Layla Kurst, Christina Bryant, Gustavo Maya, and Arlene Montevecchio.

Thanks to those I have come to know because of the issues or figures of this project: Steve Wright, Chris Green, Lee Camp, Peter Kline, Kris Norris, Kendall Soulen, Tyler Wittman, David Congdon, Myles Werntz. Thanks especially to Stanley Hauerwas, Robert Jenson, and the late John Webster, all of whom took the time to encourage this project and my work in general.

Thanks to friends in New Haven: Ross and Hayley (in more than one sense: nemo nisi per amicitiam cognoscitur), Matt and Julia, Mark and Laura, Ryan and Katie, Andrew and Josh, Mark and Liv, Laura, Val, Kelly, Kayla Beth, Roger and Elizabeth, Stephanie and Jeremiah, Stephen and Amanda. What a joy to share life with y’all these last six years. If only it could continue.

Thanks to my zealous and cheerful proof readers: Zac Koons and Lacey Jones.

Thanks to the communities that have taught and formed me in the faith: Round Rock Church of Christ, Highland Church of Christ, North Atlanta Church of Christ, St. John’s Episcopal Church, Trinity Baptist Church.

Thanks to Star Coffee and Round Rock Public Library, where much of this work was written, along with room S217 at Yale Divinity School, now (alas) a faculty office.

Thanks to Spencer Bogle, who is the reason I am in this business in the first place.

Thanks to my parents, Ray and Georgine East, who have never flagged in support or faith in me—beginning at age 17, when I declared my desire to pursue academic theology. What sort of people affirm such a vocation? Thanks especially to my mom, who over the years has read a steady stream of theology supplied by her eldest son. Apart from her I might doubt that this dissertation will be read by someone not paid to do so.

Thanks to Toni Moman—“Miss Toni”—to whom this work is dedicated, a lifelong servant and lover of God’s children. All ministers are theologians, and only God knows how many children have had their first dose of theology from Miss Toni. They are all of them better for it, as am I. Years ago I told Miss Toni that, if and when I had the chance to write a book, I would dedicate it to her. Well: it’s finally here!

Thanks to my three children, Sam, Rowan, and Paige, all of whom were born during my studies at Yale, and who make it all worth it. Sam and Row, especially, will be delighted to hear a different answer than usual to the oft-repeated question, “Daddy, are you done with work yet?”

Thanks, lastly, and most of all, to my wife Katelin, who has been my partner, companion, and best friend for nearly 13 years. We have traveled from central to west Texas, to Atlanta, Georgia, to New Haven, Connecticut, and back again. I cannot imagine doing so without her. Under God, I owe everything to her.

Soli Deo Gloria.

And yet many years, blood, sweat, and tears go into dissertations; and so the acknowledgements at their beginning are often a moment to step back and thank those who have made finishing the (by then) cursed thing possible. So far as I can tell, there are two different types of acknowledgements: minimalist and maximalist. Either the author thanks only those who contributed materially and directly to the dissertation's production (one friend thanked, if I recall correctly, only about a dozen individuals), or she mentions more or less every single human being she has met along the way—anyone from whom she has received as much as a cup of cold water. I fall in the latter category, both by temperament (being prolix in life and in prose) and by conviction (a lot of people helped me get to the point of completing this thing!).

But because one is lucky if the readership of one's dissertation exceeds single digits, the writing of acknowledgements can seem somewhat narcissistic, or at least futile. Wherefore I have opted to share my acknowledgements here on the blog. Though I completed and submitted the manuscript last May, it wasn't approved until October and I didn't officially graduate until December. So the proverbial ink has yet to dry, and while it does so, let me share with y'all the many names and institutions and communities—each and every one—that made possible, by God's grace, my earning a PhD in theology from Yale University in the Year of Our Lord 2017.

Acknowledgements

It was Thanksgiving 2011, in a living room in Starkville, Mississippi, that the idea for this dissertation came to me. ‘Came to me’ is the right phrase: the idea was not mine, but my brother Garrett’s. He, my brother Mitch, and I were killing time in between meals, talking theology as brothers do. And Garrett said, “You know, you’ve been talking about this Webster a lot lately, and before that it was Jenson, and before that it was Yoder. Maybe you should write your dissertation on their theologies of Scripture.” Five and a half years later, here we are. So my first word of thanks goes to Garrett for giving me the idea for this project, to my sister-in-law Stacy for her relaxed toleration of our weakness for the rabies theologorum, and to Garrett and Mitch together for serving as soundboards, sparring partners, and friends throughout this process—and at all other times.

Thanks to my advisor, Kathryn Tanner, for constant encouragement, support, help (not least in saving me from featuring a fourth primary figure!), availability, theological wisdom, practical insight, and (what is not native to me) love of concision and economy of prose.

Thanks to the rest of the committee: Miroslav Volf, David Kelsey, and Steve Fowl. I could not have dreamed of a more fitting, or a more formidable, group of readers for a dissertation on this topic (they wrote the books on it, after all), and their kindness, generosity, and feedback have meant a great deal.

Thanks to the other faculty members from whom I learned or with whom I worked during my time at Yale: Christopher Beeley, John Hare, Linn Tonstad, Jennifer Herdt, Denys Turner, Dale Martin, Adam Eitel. If I have learned anything during my studies, I learned it primarily by osmosis from these brilliant, friendly scholars.

Thanks to my fellow students, in the Theology cohort and in other sub- disciplines: Awet Andemicael, Liza Anderson, Laura Carlson, Justin Crisp, Ryan Darr, TJ Dumansky, Jamie Dunn, Matt Fisher, Andrew Forsyth, Janna Gonwa, Justin Hawkins, Liv Stewart Lester, Mark Lester, Samuel Loncar, Wendy Mallette, Natalia Marandiuc, Sam Martinez, Ryan McAnnally-Linz, Ross McCullough, Luke Moorhead, Stephen Ogden, Devin Singh, Erinn Staley, John Stern, Graedon Zorzi. When I rave about the program at Yale, I am raving about these people.

Thanks to other friends, teachers, and colleagues, near and far, who were a part of my academic journey. In Abilene: Randy Harris, Tracy Shilcutt, Jeanene Reese, Wendell Willis, Glenn Pemberton, Josh Love, Reid Overall. In Atlanta: Ian McFarland, Luke Timothy Johnson, Steffen Lösel, Ellen Ott Marshall, Carol Newsom, Tim Jackson, Mark Lackowski, Leonard Wills, Don McLaughlin, Patrick and Karen Gosnell, Jimmy and Desiree McCarty, Matt and Stephanie Vyverberg, Seth and Kaci Borin, Daron and Margaret Dickens, Adam and Susan Paa. And elsewhere: Junius Johnson, Ben Langford, Andrew and Lindsey Krinks, David Fleer, Lauren Smelser White, David Mahfood, Fred Aquino, and Tyler Richards.

Thanks to the Christian Scholarship Foundation, from which I received a financial lifeline two years in a row, and to Carl Holladay and Greg Sterling, who oversee it.

Thanks to the Louisville Institute, from which I received a generous 2-year doctoral fellowship, and to the new friends and colleagues I made there: Ed Aponte, Don Richter, Terry Muck, Pam Collins, Kathleen O’Connor, Aaron Griffith, Kyle Lambelet, Amanda Pittman, Leah Payne, Derek Woodard-Lehman, Tim Snyder, Lorraine Cuddeback, Layla Kurst, Christina Bryant, Gustavo Maya, and Arlene Montevecchio.

Thanks to those I have come to know because of the issues or figures of this project: Steve Wright, Chris Green, Lee Camp, Peter Kline, Kris Norris, Kendall Soulen, Tyler Wittman, David Congdon, Myles Werntz. Thanks especially to Stanley Hauerwas, Robert Jenson, and the late John Webster, all of whom took the time to encourage this project and my work in general.

Thanks to friends in New Haven: Ross and Hayley (in more than one sense: nemo nisi per amicitiam cognoscitur), Matt and Julia, Mark and Laura, Ryan and Katie, Andrew and Josh, Mark and Liv, Laura, Val, Kelly, Kayla Beth, Roger and Elizabeth, Stephanie and Jeremiah, Stephen and Amanda. What a joy to share life with y’all these last six years. If only it could continue.

Thanks to my zealous and cheerful proof readers: Zac Koons and Lacey Jones.

Thanks to the communities that have taught and formed me in the faith: Round Rock Church of Christ, Highland Church of Christ, North Atlanta Church of Christ, St. John’s Episcopal Church, Trinity Baptist Church.

Thanks to Star Coffee and Round Rock Public Library, where much of this work was written, along with room S217 at Yale Divinity School, now (alas) a faculty office.

Thanks to Spencer Bogle, who is the reason I am in this business in the first place.

Thanks to my parents, Ray and Georgine East, who have never flagged in support or faith in me—beginning at age 17, when I declared my desire to pursue academic theology. What sort of people affirm such a vocation? Thanks especially to my mom, who over the years has read a steady stream of theology supplied by her eldest son. Apart from her I might doubt that this dissertation will be read by someone not paid to do so.

Thanks to Toni Moman—“Miss Toni”—to whom this work is dedicated, a lifelong servant and lover of God’s children. All ministers are theologians, and only God knows how many children have had their first dose of theology from Miss Toni. They are all of them better for it, as am I. Years ago I told Miss Toni that, if and when I had the chance to write a book, I would dedicate it to her. Well: it’s finally here!

Thanks to my three children, Sam, Rowan, and Paige, all of whom were born during my studies at Yale, and who make it all worth it. Sam and Row, especially, will be delighted to hear a different answer than usual to the oft-repeated question, “Daddy, are you done with work yet?”

Thanks, lastly, and most of all, to my wife Katelin, who has been my partner, companion, and best friend for nearly 13 years. We have traveled from central to west Texas, to Atlanta, Georgia, to New Haven, Connecticut, and back again. I cannot imagine doing so without her. Under God, I owe everything to her.

Soli Deo Gloria.

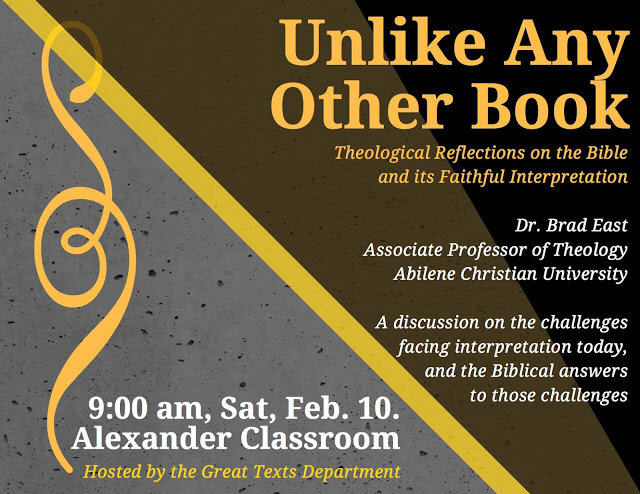

On the speech of Christ in the Psalms

Tomorrow morning I am giving a lecture to some undergraduate students at Baylor University; the lecture's title is "Unlike Any Other Book: Theological Reflections on the Bible and its Faithful Interpretation." The lecture draws from four different writings: a dissertation chapter, a review essay for Marginalia, an article for Pro Ecclesia, and an article for International Journal of Systematic Theology.

As every writer knows, reading your own work can be painful. There's always more you can do to make it better. But sometimes you're happy with what you wrote. And I think the following quotation from the IJST piece, especially the final paragraph, is one of my pieces of writing I'm happiest about. It both makes a substantive point clearly and effectively, and does so with appropriate rhetorical force. Not many of you, surely, have read the original article; so here's a sample taste:

"[S]ince the triune God is the ecumenical confession of the church, it is entirely logical and defensible to read, say, the Psalms as the speech of Christ, or the Trinity as the creator in Genesis 1, or the ruach elohim as the very Holy Spirit breathed by the Father through the Son. Perhaps some Christian biblical scholars will respond that they do not protest the ostensible anachronism of such claims, but nonetheless hesitate at encouraging it out of concern for the humanity of these texts, that is, their human and historical specificity. In my judgment, this is a well-meant but misguided concern...

"[T]he motivations behind the concern for the humanity of Scripture are often themselves theological, but these are frequently underdeveloped. A chief example is the ubiquity in biblical scholarship of a kind of reflexive philosophical incompatibilism regarding human and divine agency, rarely articulated and never argued, such that if humans do something, then God does not, and vice versa. More specifically, on this view if Christ is the speaker of the Psalms, then the human voice of the Psalter is crowded out: apparently there’s only so much elbow room at Scripture’s authorial table. And thus, if it is shown—and who ever doubted it?—that the Psalms are products of their time and place and culture, then to read them christologically is to do violence to the text. At most, for some Christian scholars, to do so is, at times, allowable, especially if there is warrant from the New Testament; but it is still a hermeneutical device, in a manner superadded or overlaid onto a more determinate, definitive, historically rooted original.

"But the historic Christian understanding of Christ in the Psalms is much stronger than this qualified allowance, and the principal prejudice scholars must rid themselves of here is that, at bottom, ‘the real is the social-historical.’ On the contrary, the spiritual is no less real than the material, and the reality of God is so incomparably greater than either that it is their very condition of being. All of which bears two consequences for the Psalms. First, God’s speech in the Psalms in the person of the Son is not in competition with the manifold human voices of Israel that composed and sung and wrote and edited the Psalter. God is not an item in the metaphysical furniture of the universe; one and the same act may be freely willed and performed by God and by a human creature. This is very hard to grasp consistently, and it is not the only Christian view of human and divine action on offer. Nonetheless it is crucial for making sense of both the particulars and the whole of what Scripture is and how it works.

"Second and finally, to read the Psalms as at once the voice of Israel and the voice of Israel’s Messiah is therefore not to gloss an otherwise intact original with a spiritual meaning. Rather, it is to recognize, following Jason Byassee’s description of Augustine’s exegetical practice, the ‘christological plain sense.’ This accords with what is the case, namely, that ontologically equiprimordial with the human compositional history of the texts is the speech of the eternal divine Son anticipating and figuring, in advance, his own incarnate life and work in and as Jesus of Nazareth. When Jesus uses the Psalmists’ words in the Gospels, he is not appropriating something alien to himself for purposes distinct from their original sense; he is fulfilling, in his person and speech, what was and is his very own, now no longer shrouded in mystery but revealed for what they always were and pointed to. The figure of Israel sketched and excerpted in the Psalms, so faithful and true amid such trouble from God and scorn from enemies, is flesh and blood in the person of Jesus Christ, and not only retrospectively but, by God’s gracious foreknowledge, prospectively as well. It turns out that it was Christ all along."

An honest preface to contemporary academic interpretation of the New Testament

The figures and authors of the New Testament, especially Jesus and Paul, taught and wrote primarily during the middle half of the first century A.D. Their teachings and texts were not, alas, understood in the 2nd century, nor were they understood in the 3rd century, nor were they understood in the 4th century, nor were they understood in the 5th century, nor were they understood in the 6th century, nor were they understood in the 7th century, nor were they understood in the 8th century, nor were they understood in the 9th century, nor were they understood in the 10th century, nor were they understood in the 11th century, nor were they understood in the 12th century, nor were they understood in the 13th century, nor were they understood in the 14th century, nor were they understood in the 15th century, nor were they understood in the 16th century, nor were they understood in the 17th century, nor were they understood in the 18th century, nor were they understood in the 19th century, nor were they understood in the 20th century. Such periods, unfortunately, were not up to date on the latest scholarship.

I am.

I am.

What I wrote in 2017, and what's coming up

Last year was momentous for me, both personally and professionally. I submitted my dissertation; I earned my PhD from Yale; I got that rarest of things, a bona fide job—teaching at my alma mater no less; I moved my family to a place we love; and I taught my first semester as a professor of theology, a dream 14 years in the making. My wife and three small children are content and flourishing, and for the first time in any of our lives, we don't have an end date bearing down on us from the horizon.

My gratitude and joy know no bounds.

I also started a new blog! (This one, just like the old one.) And I wrote some stuff, here and elsewhere, scholarly and popular. A 2017 rundown...

Scholarly:

“Reading the Trinity in the Bible: Assumptions, Warrants, Ends,” Pro Ecclesia 25:4 (2016): 459-474. Technically published in 2016, but not actually available to read in print until 2017, so I'm counting it. This article does not, unfortunately, contain this footnote, which was originally meant to be included in it.

“The Hermeneutics of Theological Interpretation: Holy Scripture, Biblical Scholarship, and Historical Criticism,” International Journal of Systematic Theology 19:1 (2017): 30–52. I think this is the best piece of scholarly writing I have published, and the most programmatic at that. If you want to know what I think about theological interpretation of the Bible in relation to historical-critical scholarship, read this.

“John Webster, Theologian Proper,” Anglican Theological Review 99:2 (2017): 333–351. After Webster's abrupt passing in 2016, I was asked by ATR to write a commemorative review article of his many books, and it was a bittersweet experience. The last few pages of the piece engage in some friendly criticism of a couple features of Webster's theology, and I'm hopeful it contributes to the beginning of the reception of his thought.

“What is the Doctrine of the Trinity For? Practicality and Projection in Robert Jenson’s Theology,” Modern Theology 33:3 (2017). I wrote the first version of what eventually became this article nearly five years before its publication, which turned out to be only months before Jenson's death at 87 years old. My argument criticizes a specific feature of Jenson's trinitarian thought, namely its (ironically Feuerbachian) projection into the triune Godhead in order to secure practical payoff for human life. Though critical, the piece comes from a place of pure affection for Jenson's work (see below).

"Review: Gary Anderson, Christian Doctrine and the Old Testament: Theology in the Service of Exegesis," International Journal of Systematic Theology 19:4 (2017): 534–537. This is an excellent book that ought to begin paving the way forward for theologians and biblical scholars alike to read Scripture together, both theologically and historically.

Popular:

"Theologians Were Arguing About the Benedict Option 35 Years Ago," Mere Orthodoxy. This piece grew out of a Twitter thread reflecting on Hauerwas and the Yale School vis-à-vis Rod Dreher. In it I use James Davison Hunter's work in To Change the World to clarify why (a) people disagree so vociferously about Dreher's proposal and (b) how the very way in which the Benedict Option is a popular distillation of ideas from the 1970s and '80s demonstrates the force of Hunter's conception of cultural change and the need for something like the BenOp. My thanks to Derek Rishmawy for suggesting I write my thoughts up in essay form and send it to Jake Meador at MO.

"Systematic Theology and Biblical Criticism," Marginalia Review of Books. A review essay of Ephraim Radner's wild and woolly and uncategorizable (not to mention un-summarizable) 2016 book Time and the Word: Figural Reading of the Christian Scriptures. This piece didn't seem to get as much play as my previous piece for MROB on Katherine Sonderegger, but it was just as pleasurable to write.

"Public Theology in Retreat," Los Angeles Review of Books. 'Tis the season of David Bentley Hart! This piece, ostensibly a review essay of Hart's three latest collections of essays, offered an occasion to reflect, in conversation with Alan Jacobs, on the nature and status (and prospects) of theology on the American intellectual scene. The feedback on this piece, even from the DBH-agnostic, was overwhelmingly encouraging. Twitter remains unarguably demonic, but the kind words of strangers who shared this essay with others was a shaft of clear, angelic light to this junior prof scribbling in west Texas.

Blog:

On the use of "everyone" in pop culture talk. (June 4 & 7) From listening to too much (never enough!) of Andy Greenwald and Chris Ryan on their podcast The Watch for The Ringer.

Figural christology in children's Bibles. (June 8) From reading my children Bible stories and noticing theological connections in the illustrations.

Four writing tips for seminarians. (June 9) From my time as a teaching assistant at Yale Divinity School.

The best American crime novelists of the last century, or: a way into the genre. (June 12) A fun diversion; who doesn't love a good list?

The liturgical/praying animal in Paradise Lost. (June 14) Riffing on Milton's anthropology in Book VII with Jamie Smith and Robert Jenson.

On the analogia entis contra Barth. (June 19 & 21) From finishing IV/1 last summer.

Teaching the Gospels starting with John. (June 30) Why not? Fie on the critics.

Figural christology in Paradise Lost. (July 10) One of my favorite things to write in 2017. Focused on the angel Michael's prophetic instructions to Adam in Book XI.

Against universalizing doubt, with a coda. (July 20 & 21) Top five favorite things I wrote in 2017. Would like to revise these together and publish in a magazine or some such thing.

Scripture's precedence is not chronological. (July 24) Expanding on a dissertation footnote on Yoder.

A question for Richard Hays: metalepsis in The Leftovers. (August 1) Having some fun while watching a great show.

Scruton, Eagleton, Scialabba, et al—why don't they convert? (August 11) A genuine question, to which a reader kindly offered a partial answer, at least for Scialabba, who once wrote briefly on the topic (in dialogue with C. S. Lewis, no less!).

What it is I'm privileged to do this fall. (August 22) Reflections on the extraordinary gift of teaching college students theology.

Rest in peace: Robert W. Jenson (1930–2017). (September 6) A bittersweet celebration of what Jenson meant to me, theologically and otherwise. This was by far the most-read piece on the blog this year, which goes to show how much this man of the church meant to so many others, too.

16 tips for how to read a passage from the Gospels. (September 14) Something I gave the freshmen in my fall course on the life and teachings of Jesus.

On John le Carré's new novel, A Legacy of Spies. (September 17) An enjoyable but ultimately disappointing trip back in time once more to the world of George Smiley.

On contemporary praise and worship music. (October 8) A fussy little missive, whose contents you can probably guess.

On Markan priority. (October 12) What would have to be the case for Mark not to be the first Gospel written? What implications would follow? How crazy is it to consider?

On the church's eternality and "church as mission." (October 20) Picking a friendly fight with the church-as-mission folks, with an assist from Thomas Aquinas.

The Holy One of Israel: a sermon on Leviticus 19. (October 25) This was a joy to write and deliver. Flexing some nearly-atrophied muscles in figural homiletics.