Resident Theologian

About the Blog

Ahab, slave to the dread tyrant Sin: Melville's dramatic exegesis of Romans 7

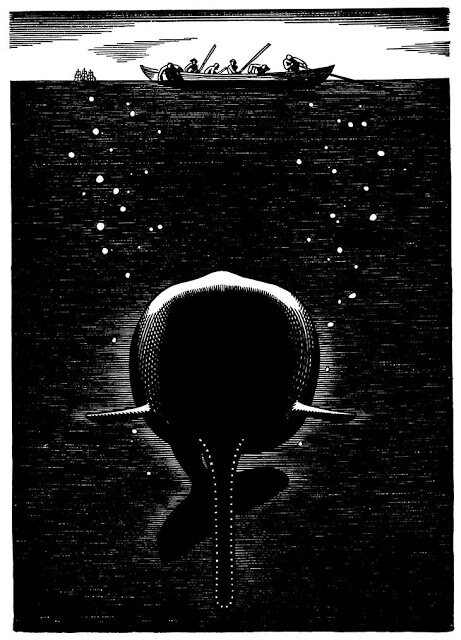

Near the finale of Moby-Dick, in the closing moments of the last chapter before the great chase for the white whale begins, gloomy Ahab has one final heartfelt conversation with Starbuck, his earnest and home-loving first mate. At the very moment when the climactic encounter is nigh, Ahab looks to pull back. And Starbuck is eager to help him do so. They converse on the deck, Ahab unsure of himself and Starbuck pleading with him, wooing him, conjuring the decision against the fatal hunt that he so hopes Ahab is capable of making. And just when Starbuck thinks he has his quarry, something inexplicable and wholly mysterious changes in Ahab. Here is Melville:

But Ahab's glance was averted; like a blighted fruit tree he shook, and cast his last, cindered apple to the soil.

"What is it, what nameless, inscrutable, unearthly thing is it; what cozening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor commands me; that against all natural lovings and longings, I so keep pushing, and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time; recklessly making me ready to do what in my own proper, natural heart, I durst not so much as dare? Is it Ahab, Ahab? Is it I, God, or who, that lifts this arm? But if the great sun move not of himself; but is as an errand-boy in heaven; nor one single star can revolve, but by some invisible power; how then can this one small heart beat; this one small brain think thoughts; unless God does that beating, does that thinking, does that living, and not I. By heaven, man, we are turned round and round in this world, like yonder windlass, and Fate is the handspike. And all the time, lo! that smiling sky, and this unsounded sea! Look! see yon Albicore! who put it into him to chase and fang that flying-fish? Where do murderers go, man! Who's to doom, when the judge himself is dragged to the bar? But it is a mild, mild wind, and a mild looking sky; and the air smells now, as if it blew from a far-away meadow; they have been making hay somewhere under the slopes of the Andes, Starbuck, and the mowers are sleeping among the new-mown hay. Sleeping? Aye, toil we how we may, we all sleep at last on the field. Sleep? Aye, and rust amid greenness; as last year's scythes flung down, and left in the half-cut swaths—Starbuck!"

Melville is playing out for us here, in dramatic form, the similar soliloquy of St. Paul in chapter 7 of his epistle to the Romans:

I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I agree that the law is good. So then it is no longer I that do it, but sin which dwells within me. For I know that nothing good dwells within me, that is, in my flesh. I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do. Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I that do it, but sin which dwells within me. So I find it to be a law that when I want to do right, evil lies close at hand. (vv. 15-21)

The "old man" weighed down by the flesh, Adam in his chains, lies in the squalor of bondage to sin—not just his own sins, but Sin, a sort of emergent personified power, a tyrant who reigns over the fallen children of Adam. Such a one is by definition unfree, and therefore utterly unfree even to choose the good, and therefore absolutely incapable of saving himself. Even with the wise route laid out before him, he cannot act. He needs a savior and more than a savior: a rival king to trample down Sin's false kingdom, and together with him to put to Death to death.

So argues Matthew Croasmun in his book The Emergence of Sin: The Cosmic Tyrant in Romans. (See further Wesley Hill's stimulating reflections on the book.) Ahab exemplifies Croasmun's thesis.

But because Melville is Melville, he's up to even more. Notice the brief, seemingly throwaway prefatory line of poetic simile: "But Ahab's glance was averted; like a blighted fruit tree he shook, and cast his last, cindered apple to the soil." Melville knows he's depicting the old man; he knows he writes of Adam. That is why he places us in a garden with a spoiled tree with its spoiled fruit "cast"—fallen—to the "soil"—adamah. And it is why, finally, he begins with the gaze: "Ahab's glance was averted." As St. Augustine writes in Book XIV of City of God, the sin of Adam was not per se the eating of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil; evil acts come from an evil will. (Augustine quotes Jesus from the Sermon on the Mount to note that evil fruit could only come—metaphorically—from an evil tree—the will of the first man.) Whence Adam's evil will, then? There is no trite answer, no easy explanation. In chapter 13 Augustine spells out the logic (italics all mine):

Our first parents fell into open disobedience because already they were secretly corrupted; for the evil act had never been done had not an evil will preceded it. And what is the origin of our evil will but pride? For "pride is the beginning of sin" (Sirach 10:13). And what is pride but the craving for undue exaltation? And this is undue exaltation, when the soul abandons Him to whom it ought to cleave as its end, and becomes a kind of end to itself. This happens when it becomes its own satisfaction. And it does so when it falls away from that unchangeable good which ought to satisfy it more than itself. This falling away is spontaneous; for if the will had remained steadfast in the love of that higher and changeless good by which it was illumined to intelligence and kindled into love, it would not have turned away to find satisfaction in itself, and so become frigid and benighted; the woman would not have believed the serpent spoke the truth, nor would the man have preferred the request of his wife to the command of God, nor have supposed that it was a venial transgression to cleave to the partner of his life even in a partnership of sin. The wicked deed, then—that is to say, the transgression of eating the forbidden fruit—was committed by persons who were already wicked.

Evil acts have their source in an evil will, and a will becomes evil when it becomes uncoupled from its true end and finds its end in itself. To become one's own end is to fall away from the true and eternal Good that alone satisfies the longings of the soul. "This falling away is spontaneous": there is no narrative, no logic, no inner rationale much less necessity, that can account for it. It just happens. The image Augustine uses for this spontaneous falling is "turning away," depicted as a kind of anti-repentance. Adam turns his eyes from God, his final End and supreme Good, to lesser things. Doing so just is The Fall.

And that is just what Melville his his Adam, Ahab, do in response to Starbuck's eminently reasonable efforts to persuade: "But Ahab's glance was averted." By what? To what? Why? We aren't told. It's spontaneous; there is no explanation to be sought because there is no explanation to be had. Ahab's turn is a surd like all sin is a surd. It has no reason, for it is no-reason, not-reason incarnate. His desire has overwhelmed his sense; his craving has overtaken his will; he himself has become his own end, and answering the command of another, from without, he rushes to his fate "against all natural lovings and longings," no matter the cost, his own life and the life of his men be damned.

Damned, indeed. Ahab is Adam without a second Adam. There is no savior in his story, even if Starbuck stands in for one as a kind of messenger or angel. Ahab, that archetypal self-made American man, is finally not the captain of his own ship. The captain of the Pequod is rather that "cozening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor" in whose service Ahab places himself when he baptizes the barb meant for the white whale: "Ego non baptizo te in nomine patris, sed in nomine diaboli."

The devil is Ahab's lord, as he is fallen Adam's master. He reigns in their death-bound lives through their bent and broken wills by the tyrannical power of Sin. Absent intervention, Adam's fate is Ahab's: to be drowned eternally in the depths of the sea, bound by the lines of his own consecrated weaponry to the impervious hide of Leviathan: the very object to which his gaze turned, the means of his helpless demise.

Wallace Stegner on the writing life of academic overachievers

I remember little about Madison as a city, have no map of its streets in my mind, am rarely brought up short by remembered smells or colors from that time. I don’t even recall what courses I taught. I really never did live there, I only worked there. I landed working and never let up.

What I was paid to do I did conscientiously with forty percent of my mind and time. A Depression schedule, surely—four large classes, whatever they were, three days a week. Before and between and after my classes, I wrote, for despite my limited one-year appointment I hoped for continuance, and I did not intend to perish for lack of publications. I wrote an unbelievable amount, not only what I wanted to write but anything any editor asked for—stories, articles, book reviews, a novel, parts of a textbook. Logorrhea. A scholarly colleague, one of those who spent two months on a two-paragraph communication to Notes and Queries and had been working for six years on a book that nobody would ever publish, was heard to refer to me as the Man of Letters, spelled h-a-c-k. His sneer so little affected me that I can’t even remember his name.

Nowadays, people might wonder how my marriage lasted. It lasted fine. It throve, partly because I was as industrious as an anteater in a termite mound and wouldn’t have noticed anything short of a walkout, but more because Sally was completely supportive and never thought of herself as a neglected wife—“thesis widows,” we used to call them in graduate school. She was probably lonely for the first two or three weeks. Once we met the Langs she never had time to be, whether I was available or not. It was a toss-up who was neglecting whom.

Early in our time in Madison I stuck a chart on the concrete wall of my furnace room. It reminded me every morning that there are one hundred sixty-eight hours in a week. Seventy of those I dedicated to sleep, breakfasts, and dinners (chances for socializing with Sally in all of those areas). Lunches I made no allowance for because I brown-bagged it at noon in my office, and read papers while I ate. To my job—classes, preparation, office hours, conferences, paper-reading—I conceded fifty hours, though when students didn’t show up for appointments I could use the time for reading papers and so gain a few minutes elsewhere. With one hundred and twenty hours set aside, I had forty-eight for my own. Obviously I couldn’t write forty-eight hours a week, but I did my best, and when holidays at Thanksgiving and Christmas gave me a break, I exceeded my quota.

Hard to recapture. I was your basic overachiever, a workaholic, a pathological beaver of a boy who chewed continually because his teeth kept growing. Nobody could have sustained my schedule for long without a breakdown, and I learned my limitations eventually. Yet when I hear the contemporary disparagement of ambition and the work ethic, I bristle. I can’t help it.

I overdid, I punished us both. But I was anxious about the coming baby and uncertain about my job. I had learned something about deprivation, and I wanted to guarantee the future as much as effort could guarantee it. And I had been given, first by Story and then by the Atlantic, intimations that I had a gift.

Thinking about it now, I am struck by how modest my aims were. I didn’t expect to hit any jackpots. I had no definite goal. I merely wanted to do well what my inclinations and training led me to do, and I suppose I assumed that somehow, far off, some good might flow from it. I had no idea what. I respected literature and its vague addiction to truth at least as much as tycoons are supposed to respect money and power, but I never had time to sit down and consider why I respected it.

Ambition is a path, not a destination, and it is essentially the same path for everybody. No matter what the goal is, the path leads through Pilgrim’s Progress regions of motivation, hard work, persistence, stubbornness, and resilience under disappointment. Unconsidered, merely indulged, ambition becomes a vice; it can turn a man into a machine that knows nothing but how to run. Considered, it can be something else—pathway to the stars, maybe.

I suspect that what makes hedonists so angry when they think about overachievers is that the overachievers, without drugs or orgies, have more fun.

—Wallace Stegner, Crossing to Safety (1987), pp. 96–98

On finding race and racism in the New Testament

I am skeptical of attempts to center contemporary Christian conversations about race on New Testament texts purported to feature or critique racism. From what I can tell, this move is a common one. Pericopes adduced include Jesus's encounter with the Syro-Phoenician woman, his meeting with the Samaritan woman at the well, and the parable of the good Samaritan. Most often, however, I see writers, pastors, and preachers use the example of gentiles in the early Jewish church, deploying some combination of Acts 15, Ephesians 2, Galatians, and Romans in order to illustrate the ostensible overcoming of racism in the early Jesus movement as an abiding example for churches struggling with the same problem today.

Why am I skeptical of this move? Let me try to spell out my reasons succinctly.

1. Race is a modern construct. What we mean by "race" does not exist in the New Testament, either as a concept or as a narratively depicted phenomenon.

2. Racism, therefore, also does not exist in the New Testament. I'm a defender of theological anachronism in Christian exegesis of Scripture, but speaking of "racism in the New Testament" is the worst kind of anachronism. It's a projection without a backdrop, a house built on sand, a conclusion in search of an argument.

3. Prejudice toward, suspicion of, and stereotyping of persons from other communities—where "other" denotes differences in region, language, cult, class, or scriptural interpretation—did exist in the eastern Mediterranean world of the Roman Empire in the first century. Inasmuch as contemporary readers want to draw analogies between forms of modern prejudice and forms of ancient prejudice, as the latter is found in the New Testament, so be it.

4. It is a fearful and perilous thing, however, to attribute such prejudice to those Jews who populated the early church or who opposed it. Why? First of all, because today it is almost uniformly gentiles who make this claim, and gentile Christians have an almost ineradicable propensity to assign to Jews—past and present—sinful behavior they seek to expunge in themselves. (See also #7 and #10 below.)

5. Moreover, Jewish attitudes about gentiles in the first century were neither uniform nor simple nor reducible to prejudice. The principal thing to realize is that, according to the witness of both the prophets and the apostles (that is, the Old and New Testaments), the distinction between Jews and gentiles is a creation of God. There are Jews and gentiles because God called Abraham and all his descendants with him to be set apart as God's holy people. All those not so called, according to the flesh, are gentiles. This distinction is maintained, not abolished, in the preaching of the gospel by the Jewish apostles in the first half century of the church's existence.

6. First-century Jewish beliefs about and relations with gentiles, then, were informed by scriptural testimony. God's word—that is, the Law, the prophets, and the writings—has a lot to say, after all, about the nations (the goyim or ethne). Go read some of it. See if you walk away with a clear, obvious, and uncomplicated view about those human communities that lie outside the election of Abraham together with his seed. Focus in particular on the book of Leviticus. Then go read chapter 10 of the book of Acts. Is St. Peter blameworthy for his hesitancy about Cornelius and his household? Is he foolish or shortsighted, much less prejudiced? Or is he following the way the words run in the Torah until such time as an angel of the Lord Jesus provides a vision paired with a divine command to act according to an alternative and heretofore unimagined interpretation of Torah? (An interpretation, note, only possible now in the light of the resurrection of the Messiah from the dead.) I'd say it's fair to think Peter, along with his brother apostles, was not in the wrong if God deemed a vision necessary to change his mind—a vision, mind you, that is didactic, not an indictment.

(7. As a historical matter, it is also worth drawing attention to the work of scholars precisely on persons such as Cornelius, gentile God-fearers and friends and patrons of the synagogue in the diaspora. The caricature of Jews living outside the land in the first century, distributed across countless cities in the Roman Empire and elsewhere, as bitter, sectarian, resentful, fearful, and hostile ethnic fundamentalists is just that: a caricature. Indeed, one should always beware of anti-Jewish sentiment lingering just beneath and sometimes displayed right on the surface of historical scholarship as well as popularized historical treatments of the Bible.)

8. As for Acts 15—the culmination, as St. Luke tells it, of Peter's vision, of Saul's conversion, of Pentecost, of the ascension, of the birth of Jesus, in fact of the calling of Abraham and the creation of Adam—the story is hardly one of racism or even of ethnic prejudice. The question for the nascent apostolic church was not whether gentiles could join. It would certainly qualify as something akin to ethnic prejudice if the exclusively Jewish ekklesia said, "We don't want your kind here." But that's not what they said. All saw and glorified God for the wonders he'd worked among the gentiles, drawing them to faith in Jesus Messiah. The question—the only question—was on what terms they would enter, that is, by what means and in accordance with what rule of life they would become members of Christ's body. Would they, like the Jews, follow the Law of Moses? Would they honor the Sabbath, keep kosher, be circumcised? Or would they not?—that is, by remaining gentiles, not subject to Torah's statutes and ordinances. Either way, they would be saved; either way, they would believe in Jesus; either way, they would receive baptism and thereby Jesus's own Spirit. The issue, in short, was not an ethnic, much less a racial, one. The issue was the will of God for those believers in Jesus who were not descendants of Abraham. And after not a little disputation and controversy, the apostolic church discerned that it was the Spirit's good pleasure for the church to comprise Jews and gentiles both, united in the Messiah as Jew and gentile, neither becoming the other nor both becoming a third thing.

9. It turns out, therefore, that the climactic tale of gentiles being welcomed into Jewish messianic assemblies around the Mediterranean Sea in the years 30–80 AD has nothing whatsoever to do with race, racism, or ethnic prejudice. Acts 15 is simply not about that. Insinuating that it does either distorts its proper significance or metaphorizes a text without grounding, or even the need, to do so.

10. None of the foregoing is meant to suggest that either the New or the Old Testament is thus reduced to silence on pressing challenges facing the American church today, not least the seemingly unexorcisable demon of anti-black racism. Nor, as I said above, is it impossible, or imprudent, to draw analogies between scriptural instances of out-group derogation and present-day experience, or between the complications arising from Jew-gentile integration in Pauline assemblies and similar complications in American churches. Nor, finally, does the wider witness of Holy Scripture have nothing to say about the bedrock principles that ought to inform Christian speech about these matters: that God is sovereign, gracious Creator of all; that every human being is created in the image of God; that each and every human being who has ever lived is one, in St. Paul's words, "for whom Christ died." I only want to emphasize what we can and what we cannot responsibly read the canon to say. More than anything, though, I want to encourage gentile Christians to be vigilant in their perpetual war against Marcionitism in all its forms. There is a worrisome tendency in recent Christian talk about white racism in America to frame it, biblically and theologically, as anticipated and foreshadowed by Jews. Even when unintended—and I have no doubt it usually is—that is a morally noxious, canonically warped, theologically obtuse, and historically false claim. The early Jewish church did not resist gentile inclusion due to its racism against gentiles. It had none, for there was none to have. There is, lamentably, plenty of racism in the world today. Look there if you want to address it. You won't find any in the pages of the Bible.

Covid, church closures, and three rationales for worship

Why do people go to church? Why do churches gather for worship on Sunday morning?

I've been asking myself this question in light of the lockdown and subsequent church closures and shifts to online streaming. And the question isn't theological so much as sociological.

After all, ordinary Christians don't go to church according to highly technical doctrinal articulations of the sort offered by systematic theologians. They have much more banal or quotidian or subjective reasons.

That's not to say those reasons aren't theological. Only that we shouldn't resort to high-level dogmatic language to explain lay folks' behavior or reasoning—or even local congregations' or parishes'. (In the case of the latter, the question isn't so much what they say explicitly but what their organization and enactment of worship "says"; what unspoken logic is embedded, implicit, in their actual liturgical practices.)

Part of the motive for thinking about this concerns the other side of society-wide lockdowns: Why would or should churches reopen? How urgent is the need or desire to do so, at the objective or subjective level? What motivates individual members of churches to delay or hasten reopening?

Here's my answer. I think, broadly speaking, there are three inner rationales for American churches' gathering for worship: sacrament, fellowship, and experience. Let me unpack these briefly.

First is sacrament. This group comprises catholic and liturgical churches ordinarily led by priests: Anglican, Orthodox, Roman Catholic, perhaps Lutheran or even sometimes Methodist traditions. Why does one go to church? Why does the church gather? Among other reasons, to receive the holy sacrament. That is the thing, the sine qua non, of Christian worship. Moreover, one cannot partake of it anywhere else. To quarantine under lockdown is one and the same as to fast from the body and blood of Christ.

Second is fellowship. This group would likely cover every manner of church across nearly all denominations. I leave "fellowship" unqualified, since it can refer simultaneously to communion with God and with fellow believers. But the emphasis is on the fellow-feeling of being gathered together with sisters and brothers in the unity of the corporate body of Christ. Such fellow-feeling is far from a natural property or a mere subjective experience; it is a spiritual and communal fact: this body of believers, right here, assembled in this space, are the sign and site of God's presence in the world. Why gather, then? Among other reasons, to enact and participate in the fellowship that Christ's Spirit makes possible when disciples congregate to worship God and hear from his word.

Third is experience. This group includes those other Protestant and especially "low church" traditions that emphasize the subjective aspect of worship. Certainly these churches are going to trend charismatic and Pentecostal, but they also include decidedly non-charismatic evangelical and non-denominational churches that place a premium on the concert-level quality of the praise band's leading of Sunday morning worship. In many ways these churches put on a weekly performance, and what attendees come for is to experience that performance. (NB: The highest of high-church liturgy is also a kind of performance, indeed a kind of extended drama; so the term itself is neutral, not pejorative.) Believers in these traditions and congregations wake up on Sundays and gather with others in order to experience what can only be had then and there: the communal, emotional, and (sometimes) charismatic energy and power of the Holy Spirit at work in mighty ways to make known the promeity—the for-me-ness—of God's love in Christ.

Suppose this typology is near the mark. What then does it say about church closings and reopenings under Covid?

First, fellowship-churches have the least intrinsic urgency to reopen. Why? On the one hand, because however attenuated, worship from home is a possibility for such communities. On the other hand, because the very thing sought in assembled worship is supremely difficult to achieve in a pandemic; mandatory mask-wearing, social distancing, no hugging or coffee hour or any of the other common ways the body is built up—these all mitigate the possibility of fellowship, both horizontal and vertical, in the extreme.

Second, sacrament-churches have the strongest inner rationale to reopen, indeed never to have fully closed in the first place. Many priests have continued unceasingly to say Mass or lead the Divine Liturgy since March, sometimes alone, sometimes with deacons or assistants, sometimes with half a dozen or so parishioners. Why? Because God ought still to be worshiped in the appointed manner by his ordained servants who stand in for, which is to say represent, the people as a whole. And because there is no digital Eucharist, no streaming sacrament, no self-feeding or solo consecration available to believers at home. (Perhaps, in fact, they view from afar and receive the sanctified elements later that day, distributed by the priest to congregants in their homes.)

Third, experience-churches are in something of a bind. On the one hand, there is a sense in which church members can participate from home: if worship is akin to a musical (or didactic!) performance, then YouTube was made for such things. On the other hand, streaming a concert and attending one are two distinct experiences. So the longer the lockdown lasts, the stronger the desire to return to in-person worship. The question for leaders at such churches is fourfold, however. First, if you build it, will they come? That is, what if your people's cautions about Covid are greater than their subjective desire to have the experience? Second, what of health precautions in worship? It's difficult to have unfettered communal experience of the Spirit in accordance with CDC guidelines (a la fellowship-churches above). Should such precautions go to the wind, given the importance of worship, or no? Third, if a church's particular appeal is the quality of the experience it has to offer, what happens when (a) the experience is no longer there to be had and/or (b) onetime attendees do some digital church shopping and find superior experiences elsewhere? Relatedly, and last, what if such church-shoppers realize the experience isn't appreciably different at home, and that streaming worship from the comfort of one's home—at a time one chooses, in a medium one prefers, while eating a snack or wearing pajamas—is preferable to the analog rigors of actually getting up and going to a physical building with other people?

I know pastors, ministers, elders, and other church leaders are asking themselves these and many other questions. I don't envy them. But it's useful to realize that not all churches are the same; not every Christian or parish has the same inner rationale for gathering or regathering under ordinary, much less extraordinary, conditions. At the very least, it's going to be illuminating to see what the American church looks like on the other side of the pandemic.

On Moby-Dick

I finally did it. Last month I read Herman Melville's Moby-Dick.

It would be an understatement to say that I loved it. I fell in love. And with all of it: the prose, the themes, the characters, the plot, the figural saturation, the endless and endlessly digressive chapters, the sheer American mythic theogony of it.

When one commits to read such heralded classics, there's always the question lingering in the back of one's mind whether it will prove a crushing disappointment. Like meeting one's heroes, reading the canon is not always for the faint of heart.

No such disappointment with Moby-Dick. Since I started it, and especially since I finished it, I have been an annoying pest to anyone and everyone who will listen to me sing of its greatness, some 170 years since its writing.

The air one breathes while reading Melville is rare. It's the same air one discovers blowing through Shakespeare, Dante, Milton, Dostoevsky, Virgil, Homer. After reading such authors, one understands the true meaning of such over-used terms like "classic," "genius," and "master." They are a class unto themselves.

Reading Melville's writing in Moby-Dick is like reading Shakespeare, only if he were an American and wrote prose. It's poetry in long-form and without line breaks. Melville did not know how to write an uninteresting sentence. The cavalcade of words builds and builds until it becomes a vast and imposing army in flawless formation, executing whatever order of subtle wit or penetrating insight Melville deigned to issue.

Did I mention he's funny? Laugh out loud funny. Every sentence in the book could be underlined, every third paragraph circled and starred, every fifth excerpted in an anthology of nothing but samples of perfect instances of American English construction.

I got bit by the theology bug early in my teens. I was dead set on my discipline from an early age. But had I read Moby-Dick at the same age, they might have gotten me instead. I mean language and lit: I might have been bound for English departments, buried beneath a rubble of 19th century manuscripts, for the rest of my life. Indeed, what makes a classic a classic, and therefore what makes Melville's opus a classic, is its inexhaustible character. Upon closing the final page, I could imagine dedicating my life to this book and this book alone. Its riches are bottomless.

Yet the one thing I can't imagine is having anything original to say about such a widely interpreted and commented-upon book. Even these reflections are little more than modest variations on the same ringing theme common to thousands upon thousands of American readers since the centenary of Melville's birth in 1919. But I'm hungry for more. I already read Nathan Philbrick's Why Read Moby-Dick? Here's to more where that came from, and above all, to many, many, many re-readings of that great mythic tome—that oceanic mishmash of Qoheleth and the Book of Job—that biblical pastiche of the enduring American soul—the undoubted and unrivaled great American novel—the one, the only, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale.

On the historical present

Les Murray on love and forgiveness

Morality and legality, killing and murder

100 theologians before the 20th century

- St. Ignatius of Antioch (d. 108)

- St. Justin Martyr (100-165)

- St. Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 130-202)

- St. Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215)

- Tertullian (c. 155-240)

- Origen (c. 184-253)

- St. Cyprian of Carthage (d. 258)

- Eusebius of Caesarea (265-339)

- St. Athanasius (c. 297-373)

10.

- St. Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306-373)

- St. Hilary of Poitiers (c. 315-368)

- St. Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 315-386)

- St. Basil the Great (c. 329-379)

- St. Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 330-390)

- St. Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335-395)

- St. Ambrose (c. 340-397)

- St. Jerome (c. 343-420)

- St. John Chrysostom (c. 347-407)

- St. Augustine of Hippo (c. 354-430)

- St. John Cassian (c. 360-435)

- St. Cyril of Alexandria (c. 376-444)

- St. Peter Chrysologus (c. 400-450)

- Pope St. Leo the Great (c. 400-461)

- St. Severinus Boethius (477-524)

- St. Gregory the Great (c. 540-604)

- St. Isidore of Seville (c. 560-636)

- Dionysius the Areopagite (c. 565-625)

- St. John Climacus (c. 579-649)

- St. Maximus the Confessor (c. 580-662)

- St. Isaac of Nineveh (c. 613-700)

- St. Bede the Venerable (c. 673-735)

- St. John Damascene (c. 675-749)

- Theodore Abu Qurrah (c. 750-820)

- St. Theodore of Studium (c. 759-826)

- St. Photius the Great (c. 810-893)

- John Scotus Eriugena (c. 815-877)

- St. Symeon the New Theologian (949-1022)

- St. Gregory of Narek (951-1003)

- St. Peter Damian (1007-1072)

- Michael Psellos (1017-1078)

- St. Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109)

- Peter Abelard (c. 1079-1142)

- St. Bernard of Clairvaux (c. 1090-1153)

- Peter Lombard (c. 1096-1160)

- Hugh of St. Victor (c. 1096-1141)

- St. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)

- Nicholas of Methone (1100-1165)

- Richard of St. Victor (1110-1173)

- Joachim of Fiore (c. 1135-1202)

- Alexander of Hales (1185-1245)

- St. Anthony of Padua (1195-1231)

- St. Albert the Great (c. 1200-1280)

- St. Bonaventure (c. 1217-1274)

- St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

- Meister Eckhart (c. 1260-1328)

- Dante Alighieri (c. 1265-1321)

- Bl. John Duns Scotus (1265-1308)

- William of Ockham (c. 1287-1347)

- Bl. John van Ruysbroeck (c. 1293-1381)

- Bl. Henry Suso (1295-1366)

- St. Gregory Palamas (c. 1296-1357)

- Johannes Tauler (1300-1361)

- St. Nicholas Kabasilas (1319-1392)

- John Wycliffe (c. 1320-1384)

- Julian of Norwich (c. 1343-1420)

- St. Catherine of Siena (c. 1347-1380)

- Jan Hus (c. 1372-1415)

- St. Symeon of Thessaloniki (c. 1381-1429)

- St. Mark of Ephesus (1392-1444)

- Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464)

- Denys the Carthusian (1402-1471)

- Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536)

- Thomas Cajetan (1469-1534)

- St. Thomas More (1478-1535)

- Balthasar Hubmaier (1480-1528)

- Martin Luther (1483-1546)

- Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531)

- Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566)

- Thomas Müntzer (1489-1525)

- Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556)

- St. Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556)

- Martin Bucer (1491-1551)

- Menno Simmons (1496-1561)

- Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560)

- Peter Martyr Vermigli (1499-1562)

- St. John of Ávila (1500-1569)

- Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575)

- John Calvin (1509-1564)

- John Knox (1514-1572)

- St. Teresa of Ávila (1515-1582)

- Theodore Beza (1519-1605)

- St. Peter Canisius (1521-1597)

- Martin Chemnitz (1522-1586)

- Domingo Báñez (1528-1604)

- Zacharias Ursinus (1534-1583)

- Luis de Molina (1535-1600)

- St. John of the Cross (1542-1591)

- St. Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621)

- Francisco Suárez (1548-1617)

- Richard Hooker (1554-1600)

- Lancelot Andrewes (1555-1626)

- Johann Arndt (1555-1621)

- Johannes Althusius (1557-1638)

- William Perkins (1558-1602)

- St. Lawrence of Brindisi (1559-1619)

- Jacob Arminius (1560-1609)

- Amandus Polanus (1561-1610)

- St. Francis de Sales (1567-1622)

- Jakob Böhme (1575-1624)

- William Ames (1576-1633)

- Johann Gerhard (1582-1637)

- Meletios Syrigos (1585-1664)

- John of St Thomas (1589-1644)

- Samuel Rutherford (1600-1661)

- John Milton (1608-1674)

- John Owen (1616-1683)

- Francis Turretin (1623-1687)

- Petrus van Mastricht (1630-1706)

- Philipp Spener (1635-1705)

- Thomas Traherne (c. 1636-1674)

- Patriarch Dositheos II of Jerusalem (1641-1707)

- August Hermann Francke (1663-1727)

- St. Alphonsus Liguori (1696-1787)

- Nicolaus Zinzendorf (1700-1760)

- Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758)

- John Wesley (1703-1791)

- St. Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain (1749-1809)

- St. Seraphim of Sarov (1754-1833)

- Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834)

- St. Philaret of Moscow (1782-1867)

- Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792-1860)

- Johann Adam Möhler (1796-1838)

- Charles Hodge (1797-1878)

- St. John Henry Newman (1801-1890)

- John Williamson Nevin (1803-1886)

- Alexei Khomiakov (1804-1860)

- F. D. Maurice (1805-1872)

- David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874)

- Isaak August Dorner (1809-1884)

- Pope Leo XIII (1810-1903)

- Heinrich Schmid (1811-1885)

- St. Theophan the Recluse (1815-1894)

- J. C. Ryle (1816-1900)

- Philip Schaff (1819-1893)

- Heinrich Heppe (1820-1879)

- Albrecht Ritschl (1822-1889)

- John of Kronstadt (1829-1909)

- Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920)

- B. B. Warfield (1851-1921)

- Vladimir Solovyov (1853-1900)

- Herman Bavinck (1854-1921)

- Ernst Troeltsch (1865-1923)

- St. Thérèse of Lisieux (1873-1897)

- Evagrius Ponticus

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Theologia Germanica

- Francisco de Vitoria

- Jose de Acosta

- Gerard Winstanley

- Blaise Pascal

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- David

Walker

- Søren Kierkegaard

- Rauschenbusch

- Alcuin of York

- Rabanus Maurus

- Paschasius Radbertus

- Cassiodorus

- G. W. F. Hegel

- George MacDonald

- Ignaz von Döllinger

- Tobias Beck

- Adolf von Harnack

- Giovanni Perrone

- Franz Overbeck

- August Vilmar

- Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet

- Léon Bloy

Joseph Ratzinger on divine providence and the divided church

Twitter, Twitter, Twitter

An update

A very special episode of Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood

New essay published: “Be Fearful as Christ Was Fearful"

Over at Mere Orthodoxy, Jake was kind enough to publish a reflection I wrote on life in a pandemic. I actually wrote it all the way back in March, just as Covid was ramping up, when there were all kinds of calls from Christian writers, pastors, and thinkers to "not be afraid" or to be "free from fear." I use St. Maximus to discuss the role of fear in the Christian life, rooted in the presence of natural fear in the life of Christ. It's called "Be Fearful as Christ Was Fearful," and here's a taste of what I'm up to:

In other words, what we see in the Garden is not for show. It is not fantasy or fiction. Christ, because he is truly and naturally human, fears death the way any bodily creature might: for to be destroyed is not good, does not belong to an unfallen world. His humanity recoils from the prospect of the passion, not out of lack of trust in the Father or uncertainty in his vocation, but because he is like unto us in every respect apart from sin. As God with us, he is one of us. And it is only human to shrink before death, even death on a cross.

But Maximus wants us to see that that is not the end of the story, because Christ’s solidarity with us is always redemptive, and so it is here, too. His fear is part of his saving work in that it is exemplary for us. For, far from obstructing his obedience to God, Christ’s natural fear becomes the occasion for it. 'Not my will but thine' is the cry of a heart faithful to God in the presence of fear, not in its absence. It is the cry of courage, which is the virtue that knows the right thing to do, and wills to do it, when disavowal of fear would mean self-deception or recklessness. In this Jesus is our pioneer, the trailblazer of truly human courage, precisely in that moment when fearlessness would be foolish. For the will of the Lord outbids even our rational fears.

In this way, Maximus helps us to see what Christian fear might mean. All of Christ’s action is our instruction, as Aquinas says. Here too: we live as Christ lived, die as he died, suffer as he suffered, fear as he feared. If we are to grieve as those with hope, but still to grieve, so are we to fear as those with faith, but still to fear.

Eleven thoughts on Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove

1. The prose is perfect. Perfect. Not perfect the way, say, Michael Chabon's is. There may not be a word in all the nearly-1,000 pages that rises above an eighth grade reading level. The sentences, moreover, are usually on the short side. The prose isn't complex. But it's pitch perfect. McMurtry never fails to communicate exactly what he intends, whether it be an action, a feeling, a thought, or a memory. Or a conversation. Oh my, the dialogue. I felt what all readers have felt reading this novel: I didn't want it to end. Like watching a sitcom for a decade, I just wanted to spend time with my friends. But anyway, reading McMurtry's prose was a delight. The way he uses euphemism and "native" construction—the way an uneducated twentysomething cowboy would think or talk—both in dialogue and in description of action or emotion from a character's perspective: it's nothing short of masterful.

2. The characters! Gus, Call, Lorena, Dish, Pea Eye, Deets, Clara—Clara!—Lippy, Newt, Wanz, Blue Duck, July Johnson, Roscoe, Po Campo, Elmira, Peach, Big Zwey, Wilbarger, Jake Spoon—oh, Jake Spoon—Cholo, Soupy, Bolivar. Each name calls forth a whole world, a flesh-and-blood person, a voice and a story and an inner dialogue. Waiting to have July open part 2 and then Clara open part 3, the latter two-thirds into the story, and for each of them to step onto the page fully-formed and wholly equal to those we'd met long before: it's invigorating, is what it is. Exhilirating for the reader. Because at that point you just don't know who might show up before long.

3. The plot is elegant in its simplicity and beautiful in its execution. An 1880 cattle drive from the Rio Grande to Montana, from the southern border to the northern (somewhere between the Rivers Milk and Missouri), led by two famous Texas Rangers in their 50s, after all the battles have been won and the land "secured" for settlement. A journey from vista to vista that live on in the American mythos. A tale filled with outsize characters and shocking events, combined with the ordinary quirks and peccadilloes of human life anywhere: back-breaking labor, bitter weather, taming the elements and animal passions in tandem, ubiquitous prostitution, city life and wilderness within walking distance, penury and plenty even closer bedfellows, unclaimed bastards and long-lost loves, abrupt deaths and children orphaned, gallows humor and gambling and ghost stories and other ways to kill the time on the short way to the grave.

3. The plot is elegant in its simplicity and beautiful in its execution. An 1880 cattle drive from the Rio Grande to Montana, from the southern border to the northern (somewhere between the Rivers Milk and Missouri), led by two famous Texas Rangers in their 50s, after all the battles have been won and the land "secured" for settlement. A journey from vista to vista that live on in the American mythos. A tale filled with outsize characters and shocking events, combined with the ordinary quirks and peccadilloes of human life anywhere: back-breaking labor, bitter weather, taming the elements and animal passions in tandem, ubiquitous prostitution, city life and wilderness within walking distance, penury and plenty even closer bedfellows, unclaimed bastards and long-lost loves, abrupt deaths and children orphaned, gallows humor and gambling and ghost stories and other ways to kill the time on the short way to the grave.4. That leads me to what most surprised me about the novel (spoilers hereon). This is a dark story lightly told. And I cannot decide whether that is a virtue or a vice (it's certainly a feature and not a bug). The tone floats upon the surface of the pages, flitting from a Gus monologue to a light-hearted memory to a gripping set piece without pausing for Existential Comment or Thematic Flag-Planting. And that, I think, is why the book (appears to me, at least) to be remembered for the joy and pleasure of the plot and the characters and the dialogue. That was certainly my experience of the first half or so. But make no mistake. This is not a comedy. It is a tragedy.

By story's end, random minor characters have died to no purpose; Jake Spoon, fallen into mindless self-justifying murder, is captured and hanged by his friends before killing himself; July's wife, who never loved him and despises him, runs off to find another man, "marries" a third and is killed by Sioux; July's stepson and best friend together with a runaway, abused little girl are brutally murdered by Blue Duck; Deets is killed by a confused and overwhelmed young Indian boy for no reason; Clara is living alone on hard plains land, with a dying husband and three dead sons in the ground; Lorena has her dreams of San Francisco dashed by being kidnapped and gang-raped by Blue Duck's crew before being rescued by Gus, only to find herself at Clara's, alone in her grief mourning Gus (perhaps losing her mind in the process); Gus himself dies randomly as a result of an accidental run-in with Blackfeet who probably would have meant him no harm if they'd met otherwise. In fact, like Jake Gus chooses to die in a fit of vanity, preferring loss of life to life without legs, thus leaving both Clara and Lorena bereft of his presence and his love. Even Wanz burns himself alive in the saloon that just wasn't the same without Lorena there.

That's only to mention the deaths. Call's bastard son by a prostitute (herself dead) lives in his shadow for two decades, only to learn from others that Call is his father; yet Call cannot bring himself to tell the boy or give him his name, and abandons him in Montana: unclaimed, unnamed, unloved, alone. Call keeps his promise to his dead friend, eventuating with him—alone—back in Lonesome Dove, without meaning or purpose or drive. Why did he take all those cattle and all those men to Montana, and tolerate all those deaths in the process, anyway? Because Jake Spoon made mention of wide green pastures? So what? Or what of Dish, love-sick for Lorena, and July, love-sick for any woman in his orbit (Ellie, Clara, ad infinitum), both too naive and foolish and earnest ever to have their love requited. Even poor Bolivar regrets leaving the outfit and joining his wife south of the border, a house empty of his beloved daughters, home only to a woman who despises him.

Not one person in the whole book proves happy by the end; not one gets what he's looking for; not one finds lasting love or satisfaction. Even Pea Eye, the least unhappy and lonesome character in the story, precisely because he asks little of life except not getting murdered in his sleep, is bewildered and set adrift by Gus's death and Call's actions toward Newt. Never one for words, he is silenced one last time.

Lonesome Dove, in short, is a desperately sad tale. It is bleak, violent, unsparing, even merciless in the fates it doles out to its characters. And yet, for probably 600 or 700 pages, that is not the way the book reads. It reads like a romp, full of color and life and simple joys and little silly detours that make you cackle with glee. It's a book to make you smile, until you don't—because you're crying, or in shock.

Is that just the way McMurtry writes? Or is it a stylistic Trojan horse—slipping in a bleak revisionist Western tragedy in the trappings of a happy well-worn genre? I'm inclined to believe it's the latter, but I confess I don't know enough to form a judgment. I'll have to do some more reading of the book's reception and interpretation to tell.

5. The book is full of provocative themes. One of the biggest is the randomness of life. That Call or Gus lived through the battles of the '40s, '50s, and '60s is sheer luck: the bounce of a rock, a horse's ill-considered step, a bullet's trajectory infinitesimally altered—they're dead, and not the living heroes they find themselves to be as aging men in the '70s. That July Johnson gets mixed up in the Hat Creek's affairs, that Jake Spoon whispers a dream of Montana to Call, is owed to nothing so meaningful as a stray bullet in Fort Smith, Arkansas. All is arbitrary, the luck of the draw. Whether some men are lucky or we merely call men lucky who live in the absence of bad luck, it's chance all the way down either way.

6. If life is random, it's also without intrinsic purpose. What meaning one's life has is mostly a matter of the meaning one assigns to it or discovers in it. Call's nature is to work, and so work he does. When the drive to work leaves him, however, he is listless, lethargic, confused. Why, again, drive cattle north, risking danger to life and limb? Why, for that matter, hang Mexican horsethieves all the while crossing the Rio Grande to steal horses from Mexican rancheros? Why pursue and clear out and kill Indians? Gus asks these questions aloud. Call dismisses them as so much nonsense. But when the question presents itself to him once all is said and done, he has no answer, for there is no answer.

7. Are Gus and Call "good men"? We readers are disposed to think so. Because we grow to love them, our affection tells us they are admirable and virtuous. Are they, though? Call is an unreflective taskmaster, and though he is a gifted leader of men, he acts for no clear higher purpose, and is quite literally possessed by violence when provoked. Gus, for his part, is larger than life, funny, clear-headed, philosophical, lettered, skilled, and wholly undetermined by others' opinions or desires. Then again, he spends most of his time doing nothing; and when not doing nothing, he is gambling, eating voraciously, busting balls, or paying a woman for sex. He openly questions whether the work of a Texas Ranger is just, and does it anyway. Would we call such a person a "good man" in real life?

8. To be sure, the novel does not "need" Gus and Call to be "good men." I imagine lovers of the novel think they are, though, and would defend the claim with feeling. Such a claim is found in one of the blurbs in my copy of the book. But I have to think McMurtry, even apart from the aim of rendering believable and interesting characters with detail and affection, intends this, too, as a kind of Trojan horse. We want to believe Gus and Call are good men because they appear to fulfill the role. But our love for them and our wanting to be in their company blinds us to a true estimation of their character. And McMurtry wants us to see, on the one hand, the emptiness of our approbation of our ancestors; and, on the other, the vacuity of any such estimation at all.

9. What McMurtry so accurately captures in this novel is the sheer givenness and there-ness of life in all its passivity and activity. The characters in Lonesome Dove rarely do things with foresight or reflection. They do them because they are the sort of things one does in their shoes. You rope the bull or drive the cattle or steal the horses or hang the thief or chase the bandits or pay the prostitute or cross the river or give or obey orders because that's just the thing to be done, the thing all of us do, here and now, in these circumstances (and not others), as the persons we are (and not others). Biases and prejudices here are not rendered in world-historical or structural terms. They're inherited, rarely thought of, and only slightly less rarely acted upon. One simply lives, typically a short while, and dies. What action occurs in between is mostly stumbled into.

10. McMurtry, though his two main female characters (Lorena and Clara) are exquisitely drawn, excels in depicting masculinity. The men of the Hat Creek outfit act exactly as men do in such conditions. The moodiness and boredom and in-fighting, the ball-busting and petty quarrels and venting of pent-up frustration, the paralyzing fear and loneliness that grips them all to one degree or another: it is as true to life as any narrative description of men in close community together as any I have ever read.

11. Perhaps my only real criticism of the book is the almost complete absence of religious matters. By this I don't mean that the novel should be theological in outlook (the way, for example, that Blood Meridian drips theological significance off every page). Nor do I mean that a character should have stood in for the Good Christian, or some such thing. What I mean is that mid-19th century Texas was a land saturated in settler-colonial European-cultural Christianity. If you were a white person in the continental United States (prior to their being United States), you belonged to a civilization that claimed the Bible and Jesus and God and Christian faith as a birthright. Even if, sometimes especially if, you were untutored and unpracticed in such faith, you talked as if you were. The vernacular was marinated in it.

And oddly, McMurtry almost never adverts to such vernacular. The boys of Hat Creek don't wonder around the campfire where they go when they die. There's no fierce defender of the name of Jesus Christ against casual sacrilege. There's no Christian burial (except for a briefly mentioned one right at the end). There's no begging Jesus for mercy with a gunshot wound in the gut. There's basically nothing of the sort. There's not even God-salted or Scripture-ornamented speech. And that seems to me a shocking historical oversight. Everything else in the novel rings true. But not this. McMurtry could well have offered his tragic vision of the old West, with no heroes or only heroes compromised by violence and vanity, a vision untainted by transcendent virtue, and yet one pockmarked by a thousand imperfect encounters with the texts and names and stories and concepts of the Christian religion. I have to think he left it out by intention, and that that intention was to give us an unfamiliar, desacralized West, godless and faithless. But the wiser course by far (as, again, the example of Cormac McCarthy attests) would be to leave the religious in, as nothing but empty ornamentation and self-aggrandizing consecration of the otherwise amoral or evil.

Had McMurtry gone that way, I might call Lonesome Dove a flawless novel. Even as it stands, I'm inclined to think it may well still be perfect.

A prediction for post-pandemic life

That's my prediction. Let me clarify what I don't mean, before I say what I do.

What I don't mean is that there won't be personal, economic, structural, and political consequences. There will be, in all kinds of ways we can and can't predict. Many people will have had Covid-19 symptoms and lived to tell the tale; many more will know someone, or know someone who knows someone, who died as a result of the virus. The U.S. and other Western nations may indeed pursue "conscious uncoupling" from the Communist regime in China; that spells uncertainty and international friction for decades to come. Supply lines, products, and consumer convenience may grow volatile and change substantially in only a handful of years. Perhaps most lasting of all, individuals and families forced into joblessness will have had to live (and may continue living) on a combination of unemployment benefits, stimulus checks, and private charity. Whole institutions, such as higher education, may be utterly transformed as a result of the global pandemic and economic shutdown. Many of my friends will be out of a job and devoid of prospects. I might be among them.

Those features are sufficient to describe a world objectively changed in the interval between "before" and "after." And perhaps this is what writers mean when they speak of how "nothing will ever be the same" or "there is no going back to normal" or "everything will be different on the other side of this."

But when I read pieces that assert variations on that theme, I discern something else. The meaning is both more specific and more general. Something like: Each of us will never be the same; the world as experienced by all of us will be utterly different. And though understandable, I think this is one of those moments that, because we cannot see to the end of it, much less beyond it, our imaginations fail when they attempt to reach forward to "life afterward."

It is true that what we are experiencing is unique. But that uniqueness won't last. Unless the death rate were to unexpectedly and rapidly spike, or the economic shutdown were to last half a decade, life will return to normal in two or three years. Again, that won't mean the conditions of our common life will be good. The financial aftershock may be devastating—but lack of jobs, awful wages, and a bad economy are, unfortunately, mundane features of ordinary life.

What I mean is that you and I won't be different. We will remember what it was like to shelter in place. But life will simply resume, mostly the way it was. The virus hasn't forced us into digging bunkers or sleeping on rooftops; neither the electric grid nor even the internet have gone down; we're not piling ten families into a single domicile, rationing scraps and burning books for warmth. We're living our lives at home—which may be bad or good, claustrophobic or monastic, abusive or supportive, lonely or bustling with multiple generations—but still home, the place to which we retire to eat or sleep on a normal day. And what we're doing when we're not working is cooking, streaming, teaching, cleaning, reading, building, going stir crazy, forming pacts with like-minded neighbors, whatever—we're not hiding in our bathrooms, or tearing down the walls for wood, or boarding up the windows out of fear.

I predict, and it's only a prediction, that in a few years this will have become a strange and somewhat surreal memory. If the economy recovers quickly, that will make it recede into the past even faster than it otherwise would. Either way, we'll be the same people we were before we quarantined ourselves. Our attention will be drawn to the next thing, however smaller or less interesting by comparison to our current moment. This will be this, and that will be that, and we'll move on. We ourselves, and the world we experience around us, will for the most part prove unchanged.

On writing and bad readers

For a while now a threefold example of this has stuck with me. It comes from one particular author's writings—a widely read academic whom we'll call Joe Johnson—and has served as a perpetual reminder of this unavoidable fact. The first stems from an essay he wrote; the other two from different reviews of different books by Johnson.

The essay was, immediately upon publication, willfully misread to mean what Johnson clearly did not mean, could not have meant, and clarified in reply that he did not mean. The misreadings seized on a few terms and a couple of minor framing devices he used in the essay in order to turn his argument inside out. It did not matter what he said to clarify; the misreaders were set in their ways.

One review was, hands down, the single most disingenuous, unserious, vicious, and uncharitable engagement with a text I have ever seen in print. Something about Johnson or the book in question clearly irked the reviewer to such an extent that rage, of an immature and pitiable sort, had to be vented in his direction. It was a sad sight to see.

The other review was calm in tone but, by its conclusion, decided that Johnson had failed in some significant way for the simple reason that (we surmise) he did not write the book the reviewer wished he had; or (to say the same thing differently) he did not end up in the "correct" ideological place by book's end. Oddly, though, even the items on the reviewer's wish list would not amount to sources of disagreement between Johnson and the reviewer; they simply never came up in the course of the book. Apparently the reviewer merely wanted Johnson to talk about them, and Johnson impolitely refused in advance.

I recall this threefold example of a single writer's plentiful experience with misreading for at least three reasons. First, if it can happen with a scholar of Johnson's stature—with a writer as generous, catholic, and lucid as he—then it will happen to anyone, including little old me. So expect it, and don't be surprised by it. Second, I confess that when I encountered each of these cases, I felt a small despair grow inside me. Why bother? That is, why bother with writing if this is the result? But then, writers I admire, such as Johnson, keep on keepin' on, in spite of these experiences, and that is exactly one of the reasons why I admire them. And since not all readers are the bad sort, writing need not be doomed to terminate in deliberate misinterpretation and misrepresentation; it might actually reach those open to its message; it might even instruct, edify, enrich, or bring pleasure to such persons. It's worth it, therefore, to try to be among those who make the attempt.

Third, though, I also remember the example of Johnson in order to remind myself: don't be one of them. At all costs, don't be a bad reader.

New essay published: “Sacraments, Technology, and Streaming Worship in a Pandemic"

I've got a new piece published over at Mere Orthodoxy called "Sacraments, Technology, and Streaming Worship in a Pandemic." In it I use the work of Neil Postman and Robert Jenson to think about the meaning and "communicability" of sacramental liturgy via mass media and digital technology, then draw some conclusions for streaming worship online today, separated as we are from public gatherings of Christ's body. I also come down pretty hard against celebrating the Lord's Supper during this unusual time of "social distancing." I hope it's useful for others, even and especially those who disagree. Blessings, and stay safe out there y'all.

A clarification on streaming worship

1. I wanted to think theologically about what is happening when Christians live-stream worship, whether that means a sermon, a praise band, mass, or the divine liturgy.

2. I wanted to observe how catholic traditions represent one rationale for streaming worship: the need for a priest and the consecration of the elements—which creates an irony, since those streaming at home cannot partake of the holy sacrament.

3. Whereas evangelical or non-sacramental traditions represent another rationale, lacking the need for an ordained person to preside at worship or consecrate the bread and wine. This suggests a different irony, namely, that such traditions permit households to conduct worship "all on their own," indeed they have long-standing histories of doing so. Which raises the question of why such churches might decide to live-stream worship, and why their members might tune in.

4. Constructively, then, I wanted to encourage these latter traditions to consider looking to their histories of "domestic devotion" and thinking about how to renew them in the minds and habits of their church members. Let a hundred thousand household churches bloom!

5. Critically, though, I wanted to express the concern that when "worship" means "a praise band leading believers in singing," and when live-streaming is mostly centered on that, then low-church traditions and their members have appeared to lose the muscle memory necessary to "do church" together in local, even household, contexts. Which can create, or might reflect, a kind of codependency that is worth recognizing for what it is, which then becomes the condition of the possibility for unlearning such codependency in the coming weeks or months of quarantine.

I hope that helps. Christians, churches, and ministers of every kind are doing all that they can in the face of an unprecedented crisis. Nothing but grace and gratitude to every one of them, including my own.

A word on Better Call Saul

A brief comment on Better Call Saul, prompted by Alan Jacobs' post this morning:

I think the show rightly understands that Kim is, or has become, the covert protagonist of the show, and by the end, we (with the writers) will similarly come to understand that the story the show has been telling has always been about her fall. No escape, no extraction, no pull-back before the cliff: she, like Jimmy, like Mike, like Nacho, like Walter, like Jesse, like Skyler, lacks the will ultimately and decisively to will the good. They're all fallen; and in a way, they were all fallen even before the time came to choose.

In this way the so-called expanded Breaking Bad universe has made itself (unwittingly?) into a dramatic parable of original sin. Not that there is no good; not that characters do not want to do good. But they're all trapped in quicksand, and the more they struggle, the deeper they sink.