Resident Theologian

About the Blog

Young Christians (not) reading, 2

Further reflections on young Christians today and their reading habits (or rather, lack thereof).

I received some really useful feedback in response to my previous post about the reading habits, such as they are, of high school and college Christians today. By way of reminder, the group I’m thinking about consists of (a) Christians who are (b) spiritually committed and (c) intellectually serious (d) between the ages of 15 and 25. In other words, in terms of GPA or intelligence or aptitude or career prospects, the top 5-10% Christian students in high school and college. Future professionals, even elites, who are likely to pursue graduate degrees in top-100 schools followed by jobs in law, medicine, journalism, the arts, academia, and politics. What are they reading right now—if anything?

(I trust my qualifiers and modifiers ensure in advance that I’m not equating spiritual maturity with intellectual aptitude, on one hand, or intellectual aptitude with careerist elitism, on the other.)

Here are some responses I received as well as a bunch of further reflections on my part.

1. One comment across the board: None of these kids are reading anything, whether they are cream of the crop or nothing of the kind. And they’re certainly not reading bona fide theology or intellectually demanding spiritual writing. All of them, including the smartest and most ambitious, are online, all the time, full stop. What “content” they get is found there: podcasts, videos, bloggers, and influencers, plus pastors with a “brand” and an extensive online presence (which, these days, amount to the same thing). To be fair, some of these online sources aren’t half bad. Some are substantive. Some have expertise or credentials or wide learning (if, often, of the autodidact sort). But to whatever extent any of these kids are acquiring knowledge, it’s not literate knowledge. It’s mediated by the internet, not by books.

2. If someone in this age range is reading a living Christian author, then I was right to think of John Mark Comer. A few more names mentioned: David Platt, Francis Chan, Dane Ortlund, Timothy Keller. I also had The Gospel Coalition mentioned as a group of authors read by some of these folks. In terms of dead authors, in addition to what I called “the usual suspects” (Lewis, Chesterton, Bonhoeffer, et al), I also heard Eugene Peterson, Dallas Willard, and Henri Nouwen. Which makes sense, since all of them have passed in recent memory, and professors as well as youth pastors would be likely to recommend their work. (I’m going to go ahead and assume John Piper is among those names, too, though he is still with us.)

3. An addendum: Some young believers are reading books, but the books they’re reading are mostly fiction. Typically YA fare; sometimes older stuff, like Tolkien or Jane Austen; occasionally scattered past or present highbrow fiction like Donna Tartt or Cormac McCarthy or Susanna Clarke. But still, not a lot of fiction reading overall, and the majority is page-turning lowbrow stuff, with occasional English-major nerdballs (hello) opting for the top-rack vintage.

4. A second addendum: It isn’t clear to me how to count or to contextualize kids who are home-schooled or taught in classical Christian academies. What percentage of the total student population are they? And what percentage of this small sub-population is being taught Homer and Virgil and Saint Augustine and Calvin and so on? Or, if we’re thinking of living authors, which if any of them are they reading? I simply have no idea what the answer is to any of these questions. Nor do I know what the difference is between such students being assigned these texts and their actual personal reading habits outside of class.

5. Back to the brief list of living authors above: Comer, Platt, Chan, Ortlund, Keller, et al. The question arises: Are young Christians who report these names in fact reading their books? Or are they “digesting” their message via sermons, podcasts, and video recordings available on the internet? The same goes for megachurch pastors with an online audience, like Jonathan Pokluda, who preaches outside of Waco; or Andy Stanley in Atlanta, or Matt Chandler in Dallas. There’s a lot of daylight between reading an author’s books and knowing the basic gist of a public figure.

6. To be even more granular: If a young Christian says that she has read Comer’s latest book, what is likeliest? That she used her eyes to scan a codex whose pages she turned with her hands? or that she read it on an e-reader/tablet? or that she listened to the audio version? After all, Comer—like other popular nonfiction authors today—reads his books himself for the audio edition. And since he’s a preacher for a living, it’s very effective, not to mention personalizing; which is part of the appeal for so many young people today.

7. In a word, is it true to say that even the readers among young believers today are often not “reading” in the classical manner many of us presuppose? So that, whether it’s a podcast or a TikTok or an IG Reel or a YouTube channel or a “book,” the manner of reception/intake/ingestion is more or less the same? So that “reading” names not an alternative mode of acquiring knowledge or engaging a source but simply a difference in type of source? In which case, it seems to me, young people formed in this way will not, would not, think of “books” as different in kind from other social media that make for their daily digital diet, but merely a difference in degree. Books being one point on a spectrum that includes pods, videos, and the like.

8. So much for technologies of knowledge production and consumption. Another question: What counts as a “serious” Christian author? That was part of my original question, recall. Not just intellectually serious young Christian readers, but serious Christian books by serious Christian authors. Not fluff. Not spiritual candy bars. Not the ghost-written memoirs of influencers. Not, in short, the “inspirational” shelf at Barnes & Noble. If one-half of the presenting question of the original post concerned a certain type of young Christian reader, the other half concerns a certain type of Christian author. Here’s what I have in mind, at least. The author doesn’t have to meet a credentials requirement; doesn’t have to have a doctorate. Nor does he have to write in an academic, jargon-laden, or impenetrable style. That would defeat the point. To be popular, you have to be readable. And “being popular” can’t be a defeater here, or else no one, however rich or good in substance, could ever sell books: they’d be disqualified by their own success.

As I’ve said, Lewis and Chesterton are the gold standard. Other names that come to mind from the twentieth century (beyond Bonhoeffer, Nouwen, Peterson, and Willard) include Karl Barth, Dorothy Sayers, Francis Schaeffer, Os Guinness, Martyn Lloyd-Jones, Madeleine L’Engle, John Stott, J. I. Packer, Robert Farrar Capon, Frederick Buechner, Wendell Berry, Stanley Hauerwas, and Marilynne Robinson. That’s a very short list; it could be doubled or tripled quickly. As it stands, what do the names on it have in common?

Here’s how I’d put it. Each author’s writing draws from a rich, clear, and deep reservoir of knowledge and wisdom, a reservoir that funds their work but does not overwhelm it. Put differently, what a normie reader encounters is the tip of the iceberg. If that’s all she can handle, so be it. But to anyone in the know, it’s as clear as day that there’s a mountain of ice beneath the surface.

Furthermore, one of the consistent effects of reading any of these authors is not only sticking with them but moving beyond them into the vast tradition that so evidently informs their writing. This could be the Thomistic tradition, or the patristic, or the Homeric, or the Antiochene, or the Kantian, or the Reformed, or whatever—but what the author offers the reader is so beautiful that the reader wants more of whatever it is. And so she moves from Piper to Edwards to Calvin to Augustine in the course of weeks, months, and years. From there, who knows what will be next?

That is the kind of book, the sort of author, I have in mind. My original interlocutor was asking about such work in the present tense. Who fits the bill? And who are young people reading? I’m willing to say that Keller fits the bill. Comer does too, in my judgment, though that is a status he graduated into with his last two books. His earlier work was far too primitivist-evangelical, far too dismissive of tradition, to qualify. But to his credit, he has clearly read himself into the tradition and now invites his readers to do the same.

I can certainly name others, like Tish Harrison Warren, who are doing the work and who are selling books. But are they having a widespread discernible influence across a vast slice of 15-25-year olds today? It’s probably too early to tell.

9. Let me think about my own trajectory for a moment. Here are authors whose books I read cover-to-cover across three different age ranges:

15-18: Lewis, Chesterton, Bonhoeffer, Kierkegaard, Tolkien

18-22: Lee Camp, Douglas John Hall, Richard Foster, Nouwen, John Howard Yoder, Hauerwas, Berry, Walter Brueggemann, N. T. Wright, Ben Witherington

22-25: William Cavanaugh, Terry Eagleton, Robert Bellah, Augustine, Charles Taylor, Barth, Robert Jenson, John Webster, Christopher Hitchens, Michael Walzer, Kathryn Tanner

These aren’t all the authors I was reading at these ages, but rather the kinds of names I was introduced to that made an impact on me—so much so that I remember, in most cases, the first book I read by each, and when and where I was, and what my first impression of them was.

I’m sure I’m leaving off some important names. But the list is representative. I was a precocious, brainy young Christian who loved talking about God and reading the Bible, and these were the authors that youth ministers, mentors, and professors put in my hands. Not a bad list! Pretty much all living authors, or from the previous century, so not a lot of historical or cultural diversity on offer. But substantive, provocative, stimulating, and accessible nonetheless. The kinds of authors who might change your life. The kind who might convert you, or de-convert you. Who might shadow you for years to come.

And so, once again, the question is: Is the 2023 version of me (a) reading at all and, if so, (b) which authors, living or dead, is he reading? which is he being poked and prodded by? which stimulated and provoked by? Inquiring minds want to know!

10. This exercise has made me take a second look at my own teaching. Which authors do I assign? If you are a student who enrolls in my class, who will you read? A rough summary off the top of my head:

Dead: Barth, Saint Gregory of Nazianzus, Saint Athanasius, Saint Thomas Aquinas, John Calvin, Martin Luther, Saint Augustine, Saint Oscar Romero, Pope St. John Paul II, Pope Paul VI, Henri Nouwen, James Cone, Gerhard Lohfink, Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Alive: Tish Harrison Warren, James K. A. Smith, Thomas Joseph White, N. T. Wright, Beth Felker Jones, Martin Mosebach, Tara Isabella Burton, Ross Douthat, Andy Crouch, Andrew Davison, Andrew Wilson, Peter Leithart, Jemar Tisby, Victor Lee Austin, Michael Banner, James Mumford

Those are just authors of books I’ve assigned (and do assign). The list would be far larger if I included authors of chapters and articles and online essays. In any case, I’m pretty happy with this list, granting that I teach upper-level gen-ed elective courses to undergraduate students who have never taken theology before.

11. What lessons do I draw from all of the above? First, that people like me have a lot of power and influence and therefore enormous responsibility toward the young people who enter our classrooms. I cannot control whether my students fall in love with the books I assign them. But if I choose wisely, I make it far more likely that they might fall in love. That might in turn set off a chain reaction of reading and learning that lasts a lifetime.

12. Second lesson: Don’t assign “textbooks.” That is, don’t assign purely academic or fake authors. Don’t assign books dumbed down for teenagers. Avoid books that do not look like any sane person would ever cozy up with them in a comfy chair and read leisurely for a whole afternoon. Instead, assign books whose authors are known for befriending their readers. Assign authors who have fanatical followings. Assign authors who have the power to convert readers to their cause. Assign poets and rhetors and masters of the word. Assign stylish writing. Assign passionate writing, writing with stakes. Assign texts with teeth. Don’t be surprised when they bite students. That’s the point.

13. Third, the express aim of Christian liberal arts education and certainly of every humanities class within such institutions ought to be for students to learn to read, thence to learn to love to read, thence to learn to desire to be (that is, to become) a lifelong reader. Every assignment should be measured by whether it conduces to this end. If it does not, it should be scrapped.

14. It follows, fourth, that professors should shy away from assigning online content, whether that be links, videos, podcasts, or even texts on e-readers. That’s not quite an outright ban, but it is a strong nudge against the inclination. Give your students books: physical books they can hold in their hands. Reading a book is an activity different from scrolling a website, watching a video, or listening to a podcast. Young people already know how to do those things. They do not know how to sit still for ninety minutes without a screen in sight, in utter silence, and turn pages, lost in a book, for pure pleasure or simple edification. They have to be taught how to do that. And it takes time. What better time than college?

15. All this applies twice-over for seminaries. What is a pastor who cannot read? The principal job of a pastor, alongside administering the sacraments, is to teach and preach God’s word, which means to interpret the scriptures for God’s people. You cannot interpret without reading, which means you cannot teach and preach without being able to read. Are we raising a generation of illiterate ministers? Is the time already upon us? Are our seminaries aiding and abetting this process, or actively opposing and redirecting it?

16. If professors have some measure of influence, youth pastors (in person) and pastors with a public platform (online) have much greater influence. What we need, then, is for pastors to see it as part of their job description to find ways to encourage and induce literacy in the young people at their churches and, further, to suggest authors and books that are more than candy bars and happy meals, spiritually speaking. For this to happen—allow me to repeat myself—pastors must themselves be readers. They must be voracious bookworms who understand that their vocation necessarily and essentially entails wide and deep and sustained reading. Their churches (above all their elders and vestries and bishops) must understand this, too. If you walk into a pastor’s office and he is reading, he is doing his job. If you never see him reading, something’s amiss. The same is true, by the way, if you do see him reading, but he’s only ever reading a book written in the last five years.

17. Returning to the academy, what happens in the classroom is not all that happens on a college campus. Much, perhaps most, learning happens elsewhere. To be sure, it happens in library stacks and dorm rooms and coffee shops and Bible studies. But it also happens at Christian study centers. The importance of these cannot be overstated. Their presence on public and non-religious campuses is a refuge and a haven for young believers. They can’t be only that, however. They have to be the kind of place that fosters learning, reflection, discussion, and—yes—reading. Reading groups on the church fathers, or the magisterial reformers, or the Lutheran scholastics, or the ecumenical councils: these should be the bread and butter of Christian study centers. Hubs of vibrant intellectual life woven into and inseparable from the spiritual.

18. I’ll go one step further (borrowing the tongue-in-cheek suggestion from a friend): What we need is Christian study centers on Christian college campuses. Sad to say, far too many Christian universities today have bought into credentialing, gate-keeping, and careerism. They do not exist to further the Christian vision of the liberal arts. They exist to stay alive by selling students a product that will in turn secure them a job. None of these things is bad in themselves—enduring institutions, diplomas, gainful employment—but they are not the reason why Christian higher education exists. The presence of Christian study centers on Christian campuses would signal a commitment to the telos of such institutions by carving out space for the kinds of activity that students and professors are, lamentably, sometimes kept from devoting themselves to within the classroom itself. Perhaps this could be done explicitly on some campuses, whereas on others you would have to do it on the sly. Either way, it’s a worthy endeavor.

19. Let me close on two notes, one negative and one positive. The negative: As I have written about before, we have entered a time of double literacy loss in the church. Christians, especially the young, are at once biblically illiterate and literally illiterate. They do not read or know the Bible, and this is of a piece with their larger habits, for they do not read anything much at all. That is a fact. It would be foolish to deny it and naive to pretend it will change in some seismic shift in the span of a few years.

The period in which we find ourselves, then, is a sort of return to premodern times: Granting a kind of minimal mass literacy, in terms of widespread active reading habits, there is now (or will soon be) a very small minority of readers—and everyone else. What will this mean for the church? For daily spirituality and personal devotion? For catechesis, Sunday school, and preaching? For lay and voluntary leaders in the church? For ordained ministers themselves? We shall see.

20. I am biased, obviously, in favor of literacy and habits of reading. I want my students to be readers. I want pastors to be readers. I want more, not less, reading; and better, not worse, reading. But not everyone is meant to be a reader. Not everyone should major in English. Not everyone’s evenings are best spent with Proust in the French and a glass of wine. God forgive me for implying so, if I have.

Here’s the upshot. If young people (and, as they age, all people) are going to learn about the Christian faith through means other than reading, and for the time being those means will largely be mediated by the internet, then what we need is (a) high-quality content (b) accessible to normies (c) funded by a reservoir of knowledge rooted in the great tradition, together with (d) ease of access and widespread knowledge of how to get it. We need, in other words, networks of writers, pastors, teachers, scholars, speakers, podcasters, and others who have resources, audiences, support, technology, and platforms by which and through which to communicate the gospel, build up God’s people, and educate the faithful in ways the latter can access and understand, with content we would call “meat,” not “milk.”

I know one such endeavor. There are others. I don’t want to give up on literacy. I never will. But we can walk and chew gum at the same time. Time and past time to get moving on these projects. I’m entirely in favor of them, so long as we do not see them as a substitute but instead as a supplement to the habits of reading they thereby encourage rather than block. What we need, though, is the right people, adequately resourced, finding the young, hungry and seeking Christ and open to learning as they are. If this is the way to reach them, and it can be done well, count me in.

Who are young Christians reading today?

What living authors are writing books that intellectually serious 15-25-year old American Christians are reading today? Are there any? Are they good? A failed attempt at an answer.

The question above was posed to me recently. What the speaker meant was: What living authors are brainy/serious/mature 15-25-year olds reading today?

I’m not sure I have an answer.

My first answer: They aren’t reading. At least, most Christians in this age range aren’t reading anything at all, much less thoughtful theology or rich spiritual writing.

My second answer: They aren’t reading, because if they are “consuming content” along these lines, it’s via YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, and Spotify. They’re listening, watching, and scrolling, no doubt. The question then becomes: To whom? To what? Is any of it good? Or is it all drivel? But that’s a question for another day.

My third answer: A few of them—the ones actually reading real books, good books, cover to cover—are just reading the old classics many of us were fed at the same age: Lewis, Chesterton, Bonhoeffer, Kierkegaard, Barth. Maybe Saint Augustine or Saint Thomas or Saint Athanasius or Julian of Norwich. Maybe, at the outer limits, Simone Weil or Saint John Henry Newman or Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. Maybe Ratzinger! Or John Stott or J. I. Packer. Not sure, to be honest. But those of my students who do walk in the door having read something have usually read Lewis or one of the other usual suspects.

Having said all this, the original question remains unanswered. Are there living authors that have genuine influence on this crowd, minute and dwindling as the crowd may be?

The only name that came to mind as a surefire answer was John Mark Comer. Beyond him, I’m simply not sure. It seems to me there is not a John Piper of this generation (granting that Piper is still with us, and still exerting some measure of influence)—someone who is read widely, loved and hated, discussed constantly, an ever-present “voice” mediating a determine set of doctrines or ideas or practices or what have you.

Maybe Tim Keller. But the pastors and laity I know who read Keller are all my age or (typically) older. I don’t know if his name makes waves among the youth; maybe, but I doubt it.

So who else? Note that I’m not asking about which “names” make waves—there are plenty of popular influencers and pastors and speakers and YouTubers and podcasters. I’m talking about authors whose books are read by 15-25-year old American Christians with a head on their shoulders, who are serious about their faith in an intellectually curious way.

Other names: Tish Harrison Warren? Esau McCaulley? Dane Ortlund? Robert Barron? Jemar Tisby? Nadia Bolz-Weber? Carl Trueman? Peter Leithart?

I don’t know, y’all. I should add, I suppose, that I don’t mean which books have sold the most from the “Christian inspirational” genre. I’m talking about heady, demanding, theologically rigorous works addressed to a popular audience but not silly, superficial, or dumbed down.

I’m open to the answer being that what I have in mind—namely, books written by bona fide authors possessed of expertise, style, and substance—is not how Christian high schoolers and college students today are being reached or even growing in their faith. Though I will admit to my skepticism that it is possible for us to raise a generation of intellectually, spiritually, and theologically mature Christians who do not, at some point, deepen their faith and understanding in this way.

Time will tell, I suppose. But I do invite additional suggestions. I teach college students, after all, but the sample size is small; I only have one classroom for anecdotal observation, and the students who walk in don’t represent everyone. What are others seeing?

Defining “culture”

Responding to Alan Jacobs’ critique of my undefined and indiscriminate use of “culture” in my recent Mere O essay.

I’ve been grateful for the responses I’ve seen to my Mere O essay “Once More, Church and Culture.” Andrew Wilson was particularly kind in a post about the piece.

I’ve especially appreciated folks understanding what I was (and was not) trying to do in it. Not to suggest Hunter’s typology is bad or discreditable. Certainly not to suggest an alternative singular image or approach. Rather, to suggest that the very search for one dominant or defining posture is a fool’s errand, not to mention historically and culturally parochial. I was worried the length and wending nature of the essay would mislead readers. I was wrong!

Alan Jacobs also liked the essay, but was left with one big question: What is “culture,” and why did I—why does anyone, in writing on the topic—leave it undefined? More to the point, “there is no form of Christian belief or practice that is not cultural through-and-through.” In which case it sounds rather odd to pit the church against something the church herself includes and which, in turn, includes the church.

Alan’s criticism is a legitimate one, and I don’t have any full-bodied defense of my unspecified use of the term. I do have a few quick thoughts about what I had in mind and why folks use the word generically in essays like this one.

First, “culture” is one of those words (as Alan agrees) that is nigh impossible to pin down. You know it when you see it. You discover the sense of what a person is referring to through their use. The term itself could call forth an entire lifetime’s worth of study (and has done so). In that case, it’s reasonable simply to get on with the discussion and trust we’ll figure out what we’re saying in the process.

And yet—this intuition may well be wrong, and its wrongness may be evidenced in the very interminability of the post-Niebuhrian conversation. Granted! I’m honestly having trouble, however, imagining everyone offering a hyper-specific definition of “culture” or avoiding the term altogether.

In any case, second, it may be true that Niebuhr made various errors in his lectures that became Christ and Culture, but I’m surprised that Alan thinks—if his tongue is not too far in cheek—that the book should be dismissed. My surprise notwithstanding, I engage Niebuhr in the essay not to defend him but to take up the ideas he put into circulation through his typology; or rather, to display the pattern in his approach, which became the template for so many who followed him.

Third, I would like to point out how I actually use the word “culture” in the essay. I do in fact mention it in the opening sentence, along with similar items in a grab-bag list meant to suggest a kind of comprehensive civic repertoire: “Christendom is the name we give to Christian civilization, when society, culture, law, art, family, politics, and worship are saturated by the church’s influence and informed by its authority.” After that, I use the term exclusively in four ways: in scare quotes, in actual quotations, in paraphrase of an author’s thought, or in generic reference to “church and culture” writing—until the final few paragraphs. Here they are:

“…Niebuhr, Hunter, and Jenson are right to see a dialectic at work in the church’s encounter with various cultures.”

“As I see it, there is no one ‘correct’ type, posture, or model. Instead, the church has four primary modes of faithful engagement with culture.”

“God is the universal Creator; the world he created is good; and he alone is Lord of all peoples and thus of all cultures.”

“When and where the time is right, when and where the Spirit moves, the proclamation of the gospel cuts a culture to the bone, and the culture is never the same.”

“…[my approach] does not prioritize work as the primary sphere in which the church encounters a culture or makes its presence known.”

“The mission of the church is one and the same wherever the church finds itself; the same goes for its engagement with culture.”

“Sometimes … the Spirit beckons believers, like the Macedonian man in the vision of St. Paul, to cross over, to enter in, to settle down, to build houses and plant vineyards. In other words, to inhabit a culture from the inside. Sometimes, however, the Spirit issues a different call…”

In my humble opinion, these uses of the term are clear. Either they are callbacks to the genre of “church and culture”/“engage the culture”/“church–culture encounter” writing, which I am in turn riffing on or deploying for rhetorical purposes (without any need for a determinate sense of the word). Or they are referring to a society or civilization in all its discrete particularity, as distinct from some other society or civilization.

Had Alan been the last editorial eye to read my essay before I handed it in, I would have cut “culture” from the first sentence and replaced most or all of these final mentions with “society” or “civilization.” I don’t think I would have defined “culture” from the outset, though I might have included a line about the term being at once inevitably underdetermined and unavoidable in writing on the topic, that is, on the church’s presence within and mission to the nations.

At the very least, I’ll be mindful of future uses of the term. It’s a slippery one, “culture” is, and I’m grateful to Alan for reminding me of the fact.

I’m in Mere O on church and culture

My latest essay, “Once More, Church and Culture,” is in the new issue of Mere Orthodoxy.

I’ve got an essay in the latest issue of the print edition of Mere Orthodoxy, and Jake has just posted it online this morning. It’s titled “Once More, Church and Culture.” Here’s the opening paragraph:

Christendom is the name we give to Christian civilization, when society, culture, law, art, family, politics, and worship are saturated by the church’s influence and informed by its authority. Christendom traces its beginnings to the fourth century after Christ; it began to ebb, in fits and starts, sometime during the transition from the late middle ages to the early modern period. It is tempting to plot its demise with the American and French revolutions, though in truth it outlasted both in many places. It came to a more or less definitive end with the world wars (in Europe) and the Cold War (in America). Even those who lament Christendom’s passing and hope for its reestablishment have no doubt that the West is post-Christian in this sense. The West will always carry within it its Christian past — whether as a living wellspring, a lingering shadow, a haunting ghost, or an exorcised demon — but it is indisputable that whatever the West has become, it is not what it once was. Christendom is no more.

Re-reading what I’ve written there (drafted last summer, I think), I’m inclined to say the opening seven paragraphs make for some of my better writing. It’s a potted history of Christendom before and in America, and how it continues to haunt Protestant reflection about “church and culture.” Part two of the essay takes up H. Richard Niebuhr’s typology and James Davison Hunter’s “faithful presence.” Part three takes a stab at an alternative framework—but not one more single-label option that captures all contexts and circumstances. Read on to see more.

And once you’ve read it, go subscribe to the Mere O print magazine. It’s great!

Two further thoughts. First, some version of this essay has been rattling around in the back of my mind since January 2017, when I first taught a week-long intensive course called “Christianity and Culture.” I’ve taught it now every single January since. That’s seven total! Didn’t even miss for Covid. The texts have varied, but I’ve consistently had students read Hauerwas, Jenson, JDH (excerpts), JKAS (You Are What You Love), THW (Liturgy of the Ordinary), TIB (Strange Rites), Douthat (Bad Religion), Dreher (the old pre-book FAQ), Wilkinson/Joustra, Tisby, Cone, and Crouch. It always goes so well. And every Friday of the course, I conclude with, basically, what I’ve written in this essay: a set of typologies; a critique of them; and my own proposal. I’m grateful to Jake for letting me finally put it down in black and white.

Second, this essay has brought home to me how much this topic has dominated my thoughts, and therefore my writing, since I finished my dissertation six years ago. Specifically, the topic of the church in relation to society, which brings in its wake questions about Christendom, America, liberalism, and integralism, not to mention missiology, culture, technology, liturgy, and even anti-Judaism. Everything, in other words! For those who may be interested, here is an incomplete list of publications that bear on these matters and thus supplement this particular essay:

Theologians Were Arguing About the Benedict Options 35 Years Ago” Mere Orthodoxy | 13 March 2017

Public Theology in Retreat Los Angeles Review of Books | 20 September 2017

Holy Ambivalence Los Angeles Review of Books | 1 March 2018

The Church and the Common Good Comment | 17 January 2019

The Specter of Marcion Commonweal | 13 February 2019

A Better Country Plough | 4 August 2019

Sacraments, Technology, and Streaming Worship in a Pandemic Mere Orthodoxy | 2 April 2020

The Circumcision of Abraham’s God First Things | 1 January 2021

When Losing Is Likely The Point | 18 June 2021

Market Apocalypse Mere Orthodoxy | 25 August 2021

Statistics as Storytelling The New Atlantis | 1 October 2021

Still Supersessionist? Commonweal | 29 October 2021

Jewish Jesus, Black Christ The Christian Century | 25 January 2022

Unlearning Machines Comment | 24 March 2022

Can We Be Human in Meatspace? The New Atlantis | 2 May 2022

Another Option for Christian Politics, Front Porch Republic | 4 July 2022

The Ruins of Christendom, Los Angeles Review of Books | 10 July 2022

The Church in the Immanent Frame First Things | 14 July 2022

The Bible in America (forthcoming in The Christian Century)

Mapping academic theology

Sharing and reflecting on John Shelton’s genealogical web of liberal mainline institutions, theologians, and ethicists in the wake of Barth.

Academic theology is a tangled web of influences and institutions. Happily, John Shelton has done us all a favor by untangling some of the thornier knots in a convenient and accessible way.

How? By creating a single image that traces lines of influence, whether direct (via graduate teaching or serving as a doctoral advisor) or indirect (via published work or working as colleagues in the same school), between and among some of the most prominent scholars of Christian theology and ethics since the 1960s. These scholars, to be clear, do not form an exhaustive list; they are Anglo-American mainline Protestants, for the most part, inhabiting (by training or employment) elite Anglo-American mainline Protestant institutions. Theologians, whether systematic or moral, from outside the Anglophone world, not to mention Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and evangelicals, are almost entirely unrepresented; as are historical and patristic and medieval and pastoral and practical and all other theological disciplines.

Nevertheless, given the institutional prestige and influence of American mainline institutions, programs, and professors, the result is both impressive and illuminating. Behold:

(You can view/download the image here.)

Some initial reactions and reflections:

Lotta dudes! To be expected, but still.

If I said this image tracks Anglo-American mainline Protestants, what I meant was: this is a web of Ivy League WASP Theologians. Which, again, is to be expected: they’re the ones with postwar clout and influence. But it’s one thing to know that, another to see it laid out this way. So few institutions producing so many students, who then become major scholars in their own right, double back, get hired by the same institution that trained them (or a sister school), and start advising students themselves. So the wheel keeps spinning.

Based on this image, it was the later boomers who began to break the all-male rule in academic theology: Tanner, Jones, Kilby, Sonderegger, Coakley, Herdt.

Cone and Carter and Katongole are here. I imagine Willie James Jennings, like Paul Griffiths, is not here because he’d be a circle unto himself, rather than participating in these lines of descent. But to complete the web (which I could, I guess, but my facility with this sort of software is less advanced than a child’s) I’d probably want to add a womanist segment that touches Cone and King and Tillich and Carter but also branches off on its own: Williams, Cannon, Townes, Floyd-Thomas, and Marshall Turman.

Not everyone on this list would fit the bill of “orthodox,” but there’s a general family resemblance that makes sense of most of the names. The same goes for the style of theology being practiced: either moral or systematic. I suspect that’s why, on one hand, someone like Catherine Keller isn’t found here; and, on the other, why we don’t see prominent Christian philosophers and analytic thinkers like Nicholas Wolterstorff, William Abraham, John Hare, Richard Swinburne, Eleonore Stump, Robert Adams, and Marilyn McCord Adams. Not to mention MacIntyre! Though he probably belongs on here in terms of influence, a la Wittgenstein and Troeltsch and the Niebuhrs.

Both Reno and Marshall converted to Catholicism after they earned their doctorates, unless I’m mistaken. Kilby has always been Catholic, I believe. Same for Cavanaugh. And Lash and Katongole. Am I missing any others? Hart is the only Orthodox theologian I spy.

There needs to be an “influenced” line running from Troeltsch to Coakley.

If the Boomers continue to sit on the academic throne, their most prominent successors, peers, and competitors are all Gen X. Which makes sense, given the trajectory of a scholar’s career: PhD in one’s 30s, emergence in one’s 40s, major contribution in one’s 50s. It seems that, as each generation comes out of doctoral programs, it takes about two decades for the field to sort itself. The upshot, from my vantage point, is that my own generation won’t know which of our peers will rise to the top for another 15 years or so.

But that’s putting the cart before the horse. The real lesson I draw from this image, granting all its omissions and incompleteness, is how diffuse and disunified the “field” of Christian theology and ethics is today by comparison to the previous three generations. As Chuck Mathewes wrote a few years ago, in a review essay of Oliver O’Donovan’s career-capping trilogy in Christian ethics, the latter works should have been a “big event”—and yet they seemed to pass by without significant comment from (again) “the field.” Mathewes observes that this would not have happened in the 1970s and ’80s, when a few figures dominated the field and their publications and reviews invariably made a splash. What we have now is many fields, sometimes overlapping and sometimes not even touching, each and all of which make some claim to Christian theology and/or Christian ethics and/or philosophy of religion and/or religious epistemology and/or comparative religion and/or critical theory and/or etc., etc. That’s just the way it is today, for better or worse.

Another thought: This is not a list of “the best” theological writers/thinkers over the last half century. One of my favorites, for example—Nicholas Healy—isn’t represented. I could always add him (he studied under Kathryn Tanner, I believe), just as many others could be added. But this web is using something of a “name-brand recognition” test. Quality and renown are not unrelated, but neither are they identical.

I haven’t even mentioned that this set of interlocking genealogies doesn’t include (which it couldn’t) biblical scholars. Where would Brevard Childs or Stephen Fowl or Richard Hays or Ellen Davis fit, much less von Rad and other peers of and successors to Barth? Contrary to popular belief, historical critics read theologians and vice versa. The lines of influence just keep expanding…

I’ve buried another lede. The unsurprising spider at the top of this web is Barth. The more surprising is Niebuhr—H. Richard, not Reinhold. Reinhold’s influence on twentieth century thought, including academic theology and ethics, was great and lasting. But H. Richard always had more theological influence (or so I think), and this map captures that nicely. Niebuhr the younger was an institutionalist, and there is a sense in which his legacy stretches longer and wider than his brother’s.

I had forgotten just how prominent Gustafson was, both as a writer and as a Doktorvater, but wow, his students make for some impressive names in Christian ethics. I’m glad to see Ramsey, too, alongside Outka, who likewise had a hand in training a number of major figures. There’s a whole Princeton–Virginia thing going on here that should be mentioned alongside Yale–Chicago and Notre Dame–Duke.

Hauerwas’s imprint on theology and ethics is probably not quite as evident from this genealogy as it should be … but then again, perhaps the proportion is good as is. From the early ’80s through the Iraq War, Hauerwas was hands down the Christian theologian, ethicist, and public intellectual on the American scene. His students flooded the job market. His books (and his students’) were everywhere, as were his big ideas—including downstream from the academy, in popular press and sermons and the like. Yet that omnipresence has subsided somewhat, certainly among scholars. Hauerwas is no longer the only game in town (not that he ever was; I’m talking felt impressions). Ethicists like Herdt and Bowlin and McKenny and Bretherton and Gregory and Mathewes and Tran (the last, Hauerwas’s student) all learned a thing or two from Hauerwas, but their project is not his. If Stout was worried twenty years ago about the American theological academy retreating into a Hauerwasian sectarian hideout, he can rest assured it hasn’t happened. In truth it was never going to happen. The worry was always overstated, even if it was responding to a real phenomenon.

If I were a whiz with Adobe I would want to color code this map and create more complicated lines of relation. For example, Tanner and Volf have now been colleagues at Yale for more than a decade, and many students have had and continue to have both of them on their dissertation committee (I speak from experience!). Or think of McFarland and Jackson at Emory, or Stout and Gregory at Princeton, or Jones and Mathewes at UVA, so on and so forth. Sometimes an advisor is a hegemon; sometimes a committee is a genuine group effort. It would be useful, therefore, to be able to track who was colleagues with whom, and when, and for how long, and which students they co-advised or co-taught.

I thought of another A+ theologian not on this list, akin to Healy: Paul DeHart, who studied under Tanner at Chicago and has taught at Vanderbilt for years.

I don’t see anyone born in the 1980s (or later). Are Tran and Tonstad the lone “young guns” on this list? I imagine I’m overlooking or forgetting someone.

Just as this image is not per se about quality, it also doesn’t give an accurate perception of a given theologian’s influence or readership simply through his or her writing. I’m thinking of Jenson, Webster, Volf, and Vanhoozer. A stranger to the guild would suppose them on the margins, either in terms of their training or in terms of their reception, when the truth is the opposite. The same goes for names I’ve already mentioned, like Willie Jennings, Paul Griffiths, and Delores Williams.

Ah, I see that Bruce McCormack is not on here. He obviously fits, given Barth, Jüngel, Jenson, Hunsinger, Hector, et al.

In one of his books criticizing the Jesus Seminar, Luke Timothy Johnson adds up the total number of doctoral programs represented by participants in the Seminar in order to show the lack of professional, disciplinary, and ideological diversity represented. Academic theology is no different. In one sense that’s perfectly fine: great programs house great teachers who train great students. But it’s important to remember just how small and incestuous this world is. And thus it’s good to get outside of it once in a while. And to listen to voices who never belonged to it. The autodidacts and polymaths and fundies have a thing or two to teach elites, easy though it is to forget that.

I said the world portrayed on this map has fractured and split and multiplied. Is it also dying? The reputational prestige of liberal mainline theology and its institutions was always a corollary of the numerical quantity, sociopolitical influence, and sheer existence of liberal mainline churches. But as those have died off or entered hospice care, what of their institutions, their seminaries, their endowed chairs, their theological scholars? We’re living in the midst of a shift. The money is still there. Does the funding have a constituency? Do these institutions create a new constituency out of whole cloth? Or is their waning, absorption, and disappearance a fait accompli? I think we’re about to see. Two or three generations from now we’ll know the answers to those questions.

I’m going to need someone to make similar versions of this web for Catholic theologians (centered on Notre Dame?) as well as adjacent fields like patristics and biblical studies and analytic philosophy. I lack the knowledge and time. But it would be fascinating to see them, not to mention to see if someone could somehow combine them with one another and with this image. Perhaps an interactive 3-D model housed online? Get on it, youngsters!

I had one last thing to add—a bright clear thought in my mind, something significant—but it vanished when I came to a new bullet point. I’ll update this post if I remember. For now I welcome any and all thoughts, additions, corrections, and other feedback. Send it my way or Shelton’s. He’s the instigator and author here. I’m just using his work to think out loud. Kudos to him for some stimulating off-hours labor, just for fun.

Updates:

Vincent Lloyd. Another name that should be added. Turns out there’s a whole Union thing going on, too…

I remembered the comment that slipped my mind. In my imaginary color-coded update, figures would be denominated not only by their institutions, colleagues, teachers, and students, but by the nature of their contributions. In other words, everyone on this map has made some sort of scholarly contribution. Not everyone, though, has ventured into the world of magazines, essays, podcasts, and public speaking. Not everyone, that is, writes for a popular audience or attempts the “public intellectual” thing. But some of them do. Some of them, perhaps, do as much of that as they do the academic thing; occasionally some do more of the one than of the other. It’s a delicate balancing act, after all. You could even mark the careers of some as a kind of “before” and “after.” Think of Tony Judt, as an example outside the guild. He became a public intellectual after his major contributions added up to something so impressive the editors and readers of (e.g.) the NYRB and NYT had to sit up and pay attention. He began to write for them, and all of a sudden his scholarship had a “public.” I’m wondering the same thing about some of the folks on this micro-genealogy.

To Osten Ard

A celebration of Osten Ard, the fiction world of Tad Williams’ fantasy trilogy—my favorite of the genre—in preparation for the sequel series, a tetralogy that concludes later this year.

I first journeyed to Osten Ard in the summer of 2019. Osten Ard is the fictional world of Tad Williams’ fantasy trilogy Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn. It came out about thirty years ago and comprises three books: The Dragonbone Chair (1988), Stone of Farewell (1990), and To Green Angel Tower (1993). The last book, if I’m not mistaken, is one of the largest novels ever to top the New York Times bestseller list. At more than half a million words, it is so big they had to split it in two volumes for the paperback edition.

I enjoy fantasy, but I’m no purist. I’ve not read every big name, every big series. Nevertheless, not only is MST my favorite fantasy series. It’s the most purely pleasurable and satisfying reading experience I’ve ever had.

I remember wanting, at the time, to write up why I loved it so much. I had a whole post scribbled out in my head. Alas, I never got around to it. But I’ve finally decided to revisit Osten Ard, so I’m taking the chance now.

The reason? A full three decades after the publication of The Dragonbone Chair, Williams decided to write a sequel trilogy. That trilogy has expanded into a tetralogy, accompanied by three different smaller novels: one that bridges the two series (The Heart of What Was Lost [2017]), plus two distinct prequels set thousands of years in the past (Brothers of the Wind [2021] and The Splintered Sun [2024]). As for the tetralogy, it’s titled The Last King of Osten Ard, and includes The Witchwood Crown (2017), Empire of Grass (2019), Into the Narrowdark (2022), and The Navigator’s Children (2023). That last novel is finished and due to be released this November.

Since first reading MST in 2019 I’d been waiting for a definitive publication date for the final book of the sequel series before plunging in. Now that it’s here, I’m ready to go. But in order to prepare, I’m rereading the original trilogy via audio. It’s even better the second time round. Narrator Andrew Wincott is pitch perfect. The total number of hours across all three books is about 125—but already the time spent listening has been a delight. And then, once I’m done, I’ll open the bridge novel and the final four books that bring the whole 10-book saga to a close.

I’ve buried the lede, though. What makes these books so wonderful?

In a word: Everything.

Plot, prose, character, world-building—it’s all magnificent and then some.

1. Plot reigns in fantasy. Without a good plot, there’s no story worth telling. And what a story MST tells. It’s a slow burn in the first book. The first quarter sets a lot of tables before any food is served. I’ve had multiple friends begin the book and not make it past the halfway point for this reason. I get it. But I don’t mind the pace. All the pieces on the board have to be in the right place before the action begins. Besides, Williams’ leisurely pace is a welcome break from needing to Begin The Adventure! on page one.

Williams plots out everything in advance, and it shows. He also clearly loves four-part stories over three-parters. Every other series he’s written besides MST has entailed four books—and the third book in this trilogy is the size of the first two books put together! In any case, Williams always knows where he’s going, and he’s going to earn every step of the way. He never cheats. Never. That’s what makes To Green Angel Tower so extraordinary. Every single thread finds its way woven into the tapestry, always at just the right moment, when you least expected it. By novel’s end, the final achievement is a marvel to behold.

And even granting the slow burn of the first novel, by two-thirds of the way through, it’s off to the races, and you never look back or slow down.

2. The prose is delightful. Not showy, but not inert either. Williams has style. Above all, it’s not a failed attempt at Tolkienese. It’s “modern,” if by that one means tonally consistent, character-specific, emotionally and psychologically rich, morally complex, and written for adults. But not “adult.” Williams comes before George R. R. Martin—many of whose themes and even plot devices are lifted right off the page of MST—and beats him to the post-Tolkien punch, without any of the lurid, gratuitous nonsense. There’s neither sadism nor titillation on display here. Neither is it for kids, however. My 9-year old is reading Lord of the Rings at the moment. He won’t be ready for Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn until he’s in high school.

All that to say: For my money, granting that the genre is not known for its master stylists, Tad Williams writes the best prose in all contemporary fantasy. You’re always in good hands when you’re reading him.

3. The characters! Oh, the characters. Just wait till you meet them, till you’ve met them. Binabik, Isgrimnur, Morgenes, Jiriki, Tiamak, Josua, Miriamele, Pryrates … and so many more. One of the delights of rereading (=listening to) the trilogy is spending time with these old friends (and not a few enemies) once more.

And again, thankfully, we don’t have a Fellowship redux. There is a wizard-like character, but he plays a minor role and is nothing like Gandalf. There is more than one “good king,” in this or that kind of exile, but not only are our expectations of their “return” turned upside down; they aren’t cast in the mold of Aragorn (or David or Arthur or Richard the Lionheart or whomever). Likewise there are elf-like creatures, but they aren’t patterned on Legolas or Galadriel or the other elves of Middle-Earth. So on and so forth.

Two further comments on this point.

First, speaking of LOTR, here’s one way to understand what Williams is up to in the series. Tolkien famously ends his story with Aragorn’s accession to the throne and his long future reign and happy marriage. Williams begins his story where Aragorn’s ends: after 80 years of a happy, just, and celebrated royal reign. I.e., with the death of a universally beloved “good king.” In a sense, his story poses the question: Okay, suppose an Aragorn really did rule with peace and justice for as long as he lived. What happened next?

And then he asks: And what if this Aragorn had demons in his past, skeletons in his closet, bodies buried where no one thought to look? What if he had secrets? And what if those secrets, once brought to light, had costs?

To be clear, Williams is neither a cynic nor (like GRRM on his lesser days) a nihilist. But he wants to tell a full-bodied story about three-dimensional characters. No one’s a cardboard cutout; nobody’s perfect. That’s his way of honoring Tolkien without aping him.

Second, the protagonist of MST is a boy named Simon (Seoman) who, for much of the story, has a lot of growing up to do. He’s an orphan scullion in his mid-teens, as the story begins, and the truth is he’s petty, immature, self-regarding, self-pitying, and annoying. A real whiner, to be honest. And some folks I’ve known who gave Dragonbone Chair a chance finally put it down because they simply didn’t like Simon.

I get it. He’s not likable. He’s Luke from A New Hope, only if Luke was the same restless spoiled brat for multiple movies, not just the opening hour. Who wants to watch that?

Stick with it, is all I have to say. Williams doesn’t cheat here either. His depiction of Simon is honest and unflinching. Who wouldn’t be self-pitying and immature growing up in the kitchens of a castle without mother or father, aching for glory but ignorant of the world? Williams won’t let him grow up too fast, either. It takes time. But the growth is real, if incremental. And by the time he fully and finally grows into himself, you realize the journey was worth it. You learn to love the ragamuffin.

4. What fantasy is worth its salt without world-building? Middle-earth, Narnia, Westeros, Hogwarts, Earthsea, the Six Duchies … it either works or it doesn’t. When it works, it’s not only real, not only lived in, not only mapped and named and historied in painstaking detail. It’s appealing. It’s beautiful. It draws you in. It’s a world that, however dangerous, you want to live in too, or at least visit from time to time.

Osten Ard fits the bill in spades. It’s got all the trappings of the alt-medieval world universally conjured by the fantasy genre—fit with pagans and a church hierarchy, castles and knights, fiery dragons and friendly trolls, magical forests and mysterious prophecies—but somehow without staleness or stereotype. The world is alive. You can breathe the air. You can, once you master the map, move around in it, trace your steps or others’. It’s a world that makes sense. There’s not a stone out of place.

It’s a world with real darkness in it, too. Not the threat of it. The genuine article. Pain and suffering, remorse and lament, even sin find their way into the characters’ lives. As he wrote To Green Angel Tower, Williams was going through some real-life heartache, and you can feel it in every word on the page. But it’s not for its own sake. It serves the story, and it’s headed somewhere. If I said above that I’ve never been more satisfied by a reading experience, then I’ll gloss that here by saying that I’ve never had the level of catharsis that Williams provides the reader—finally—in the final two hundred pages of this trilogy.

And yet, apparently, that isn’t the end of the story! Williams is a master of endings, and I can call to mind immediately the closing scene, even the final sentence, of each of the three books. The first is haunting and sad; the second is mournful though tinged with hope; the third is full of joy, so much so it makes me smile just thinking about it.

But there are four more books to go! Another million (or more) words to read! A good friend whom I introduced to the original trilogy says the new series is even better than the first. Hard to believe, but I do. Between now and November—or should I say Novander?—I’m making my return to Osten Ard. Like Simon Pilgrim, I’m starting at the end, or perhaps in the middle. Usires Aedon willing, I’ll see you on the other side.

I’m in First Things + on a podcast

Links to a new essay in the latest issue of First Things and an interview on a new podcast called The Great Tradition.

An essay of mine called “Theology in Division” is in the new issue of First Things. Here’s a link. I’ve had something like it half-written in the back of my mind for the last five years. I’m glad for it to be in print finally. I’m also glad for it to honor both Robert Jenson and Joseph Ratzinger, two theologians whose legacy I treasure who have now gone on to their reward.

I’m also on the latest episode of a new podcast called The Great Tradition. We recorded the interview back in December. It’s about the Bible. This time I’ve got a good mic, so I don’t sound like I’ve yelling through feedback the whole time.

After declining invitations to appear on podcasts for years, I’ve now been on 5-10 of them over the last 12+ months. My line used to be “Friends don’t let friends go on podcasts before tenure.” I have tenure now, so I guess I’m covered. In any case, I’ve come to enjoy the interviews. This one was fun, and I think we found a way to cover all the main theological issues raised by my two books on Scripture.

Prestige scholarship

My pet theory for academics and other writers who appear to be superhumanly or even supernaturally productive.

No, not that kind of prestige. I mean the kind you find in Christopher Nolan’s movie of the same name, based on the (quite good, quite different) novel by Christopher Priest. Wherein—and here I’m spoiling it—a magician so committed to entertaining audiences and to defeating his competitor uses a kind of real magic, or outlandish science, to make a copy of himself each night, drowning the old man and watching from afar. Why does he do it? Why go to such lengths? Because, little does he know, the trick performed by his competitor, in which he seems to be in two places at once, is a con: he’s not one man but two; identical twins. That’s why he, the competitor, appears to be so superhumanly productive, so supernaturally capable of bilocation. He does exist in two places at the same time. Because he’s not one person. He’s two.

That’s the way I feel about people I think of as super-scholars. There are many of these on offer, but I’ll use Timothy Burke as an example for now. The man writes a daily Substack, almost always with a word count in the thousands. He reports continuously on the books he’s reading, the New Yorker articles he’s reading, the peer-reviewed journal articles he’s reading, the comic books he’s reading, the genre fantasy he’s reading, the novels he’s reading, the Substacks he’s reading—and more. In addition, he reports the dishes he’s cooking, the video games he’s playing, the photos he’s editing, the book manuscripts he’s drafting, the syllabi he’s re-writing, the institutional meetings he’s attending. Oh, and he has a spouse and children. Oh, and he teaches classes; something he’s apparently well regarded for.

Reading him isn’t masochistic for me so much as uncanny. He belongs to this (in my eyes fictitious but clearly all too real) tribe of academics and journalists who appear never to sleep, only to consume and produce, consume and produce, without end or exhaustion. Do they speed read? Are they lying? Do they refuse to close their eyes except for six carefully timed and executed 20-minute naps every 24 hours? Are they brains in vats operating their bodies from afar? Do they have assistants and researchers doing the actual work that comes into my inbox every single day of the week?

No, I don’t think so. They’re really doing all of it. It’s them. No tricks.

Well, except the one. Like Alfred Bordon in The Prestige, there’s more than one of them. Sometimes twins, sometimes triplets; occasionally more. Nothing magical. No futuristic science involved. They just don’t want us in on the secret. Which I get. I wouldn’t either. The result is marvelous, even unbelievable.

It’s prestige scholarship. It’s the only explanation. Good for them.

A new book contract! And other coming attractions

Happy news to share about a new book contract with Eerdmans! Plus a list of additional forthcoming writing projects: other books as well as essays and reviews.

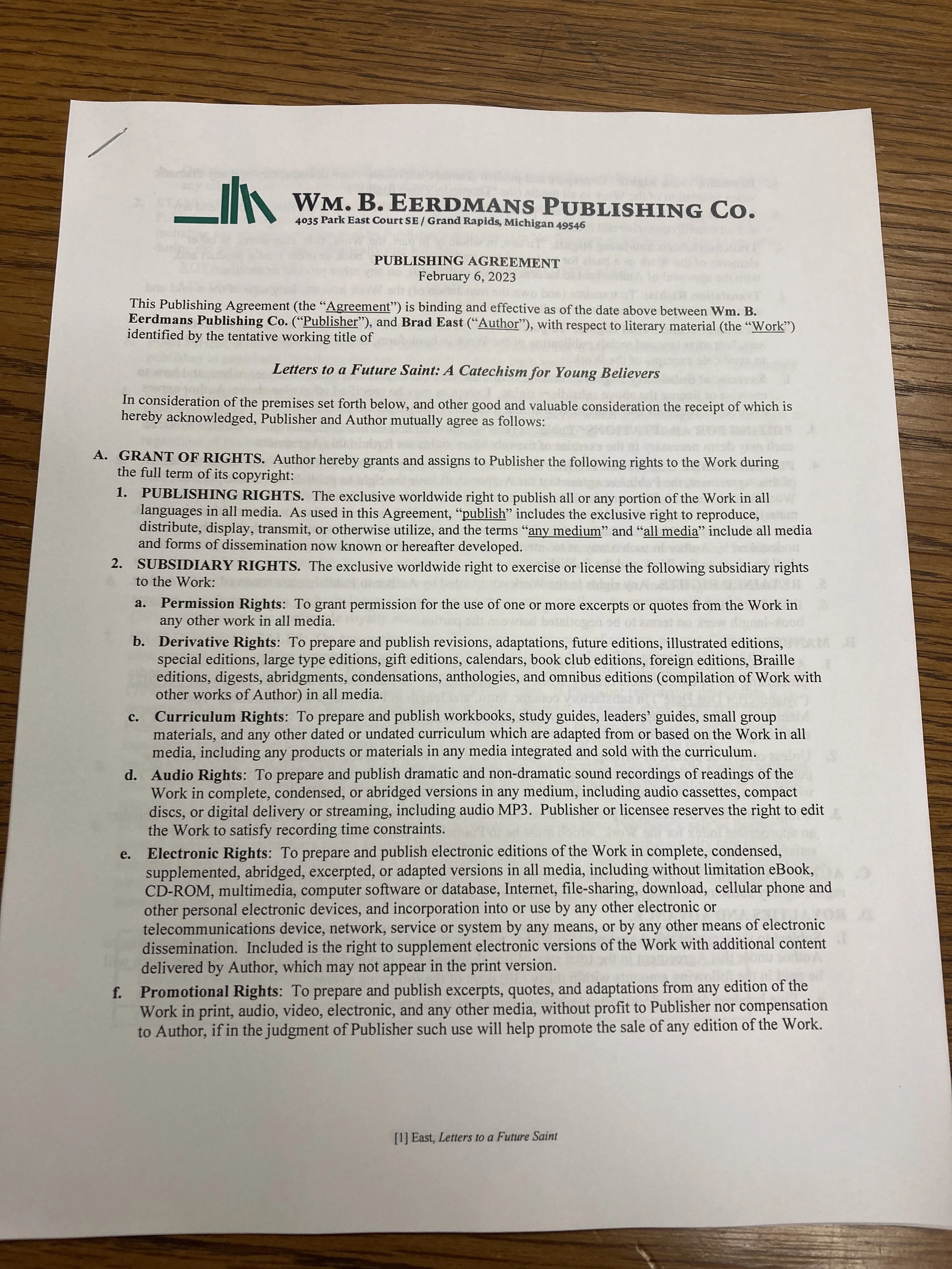

It’s official!

This week I received and signed the contract for my next book. Eerdmans is publishing it, and the tentative publication date is late 2024. The title is Letters to a Future Saint: A Catechism for Young Believers. It is what it sounds like: an epistolary catechism intended for readers in their late teens or early twenties. Not an apologetics for nonbelievers, but a catechism for would-be believers, folks who’ve grown up in the church, or perhaps in its orbit, but are relatively ignorant about the ABCs of the Christian faith while hungry to learn more.

I drafted a good two-thirds of the book in a brief but intense span of time last year, then sat on it. Now that the contract’s official, the writing will re-commence forthwith. I hope to have a rough draft by this summer, and then it’ll be time to revise the manuscript to the death. I want this thing to be perfect—by which I mean, not perfect, but absolutely accessible to my intended audience, and not only accessible, but appealing, fascinating, stimulating, even converting. I want not one word out of place. So I’m sure I’ll be road-testing it on some students in the summer and fall.

I’ve known this was coming down the pike for a while, but I didn’t want to make an announcement until it was for sure. I couldn’t be more excited. I can’t wait to share the final product with the world. I hope it finds a real readership and makes a real difference, however modest.

*

While we’re on the topic, here is a larger update on other writing projects, whether books or essays, imminent or far off.

–My first two books were published in the fall and spring of 2021 and 2022, respectively. The first was about the Bible. The second was about the Bible and the church. Book #3, not yet released, is about the church. (Are you sensing a theme?)

That book is written and in the hands of the publisher. It’s called The Church: A Guide to the People of God, and it will be the sixth entry in Lexham’s Christian Essentials series. The first five treat the Apostles’ Creed (Ben Myers), The Ten Commandments (Peter Leithart), The Lord’s Prayer (Wesley Hill), baptism (Leithart again), and the Bible (John Kleinig). I’ve read all of them, and each is fantastic. I’ve assigned more than one of them many times in classes. I’m honored to join the series. I’m eager to read the entry on the Eucharist, whoever ends up writing it!

The publication date for my entry on the church is TBD, but my guess is sometime between December 2023 and March 2024.

–Book #4 is my big news above, and as I said, I expect it to be released sometime between late 2024 and early 2025.

–Book #5 is not news, as I signed the contract nearly two years ago. It will likewise be with Lexham, in another series called Lexham Ministry Guides. The subtitle for the series and for each book in it is For the Care of Souls. Four have been published so far: on funerals, stewardship, pastoral care, and spiritual warfare.

My entry in the series will be on the topic of technology. Specifically, the role and challenge of digital technology in the life of pastoral ministry. It’s a topic close to my heart and one I’ve developed a class on here at ACU. The book will be midsize and written for ordained pastors in formal church ministry of some kind. I hope it will not be like other books of this sort. We shall see.

Anyway, I expect that book to be published in the spring or summer of 2026. And beyond that, while I have more book ideas germinating—one in particular, a “big” scholarly one—no contracts or hard plans are in place. I’d be surprised if I didn’t take a bit of a break after this one. After all, if everything goes according to plan, and God is so gracious as to permit it, I’ll have published five books in a stretch of about five years. That’s a lot. Readers, editors, and publishers will have to tell me at that point whether they want more from me, or whether that’s good enough, thank you very much.

*

As for other writing…

–My most recent peer-reviewed journal article came out last fall. I don’t currently have another one teed up, but I do have an idea for one. I’m going to let it ruminate for a while. It’s about Israel, the church, the Torah, and Saint Paul.

–In the next print issue of Mere Orthodoxy I have an essay called “Once More, Church and Culture.” It’s a reflection on Christendom, America, Niebuhr, and James Davison Hunter. Not quite an intervention, but I do offer a constructive proposal.

–In the print edition of First Things I have a reflection forthcoming on what it means to do theology when the church is divided, as it is today. This one’s a long time coming, because it is an answer to a question I get all the time about my ecclesial identity. I’m pleased to see it in the magazine, a first for me.

–This summer I have a chapter in a book published by Plough on the liberal arts. The volume came out of the grant project I was a part of called The Liberating Arts. More on this one soon.

–This summer I am writing a chapter for a book due to be published in 2024 dedicated to the topic of teaching theology. I won’t say much more about it at the moment, but I’m positively giddy to be included in the volume. Anyone in theology will recognize pretty much every name in the collection—minus mine. I still can’t believe I was invited to contribute. And I love the idea of theologians writing about teaching, which is a practice too many of us were trained to avoid or at least to resent the necessity of.

–Later this month (or next), I’ll be part of a symposium in Syndicate on Miroslav Volf and Ryan McAnnally-Linz’s new book The Home of God: A Brief Story of Everything. Should be good fun.

–Later this spring I should have a review essay in The Christian Century on Mark Noll’s book America’s Book: The Rise and Decline of a Bible Civilization.

–Possibly this spring or summer I might have an essay in The Point that uses Wendell Berry’s new book on race, home, and patriotism as a point of departure. I’ve got the green light, but I also have to sit down and do the thing…

–In Restoration Quarterly I plan to publish an essay on churches of Christ, evangelicalism, and catholicity, building on and synthesizing my series here on the blog last summer/fall.

–In the Journal of Christian Studies I plan to write a defense of holy orders from and for a low-church context that spurns ordination and affirms the priesthood of all believers.

–In Comment I’ll be writing a review essay of Christopher Watkin’s Biblical Critical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture. Kudos to Brian Dijkema, editor extraordinaire, for nudging me into it.

–My review of Jordan Senner’s book on John Webster just came out in Scottish Journal of Theology.

–My review of David Kelsey’s Human Anguish and God’s Power is with the editors at the Stone-Campbell Journal; I imagine it’ll be published later this year.

–My review of Fred Sanders’ Fountain of Salvation is with the editors at Pro Ecclesia; should be published soon.

–Same for my review of R. B. Jamieson and Tyler Wittman’s Biblical Reasoning, to be published in the International Journal of Systematic Theology.

–I’ll soon be writing a (long) review of Konrad Shmid and Jens Schrötter’s The Making of the Bible for the journal Interpretation.

–I’ve already recorded an interview for the podcast The Great Tradition; the episode should drop by month’s end.

–I’m giving talks here and there, in Abilene and elsewhere, but nothing to advertise here.

And I think that’s it. For now. Thanks for reading. Much to come. Now back to work.

Christians and politics

A reflection about Christians’ involvement in democratic politics, prompted by Richard Beck’s series on the subject.

My friend and colleague Richard Beck did me the honor of writing a seven-part series in response to a post I’d written last May, itself a reply to a previous post of his a few days prior. I told him I’d find the time to write about the new series, but I haven’t found it until now.

There’s much to say. As it turns out, Richard and I are not far apart here, but our instincts lead us in slightly divergent directions. Let me see if I can summarize his own views before laying out my own.

Richard begins by taking my point: In a liberal democracy, it can be an all-or-nothing proposition for Christians; namely, electing (or not) to be politically active and engaged. He allows that perhaps his hope for a kind of holy ambivalence, to use Jamie Smith’s phrase, is unrealistic. Democracy saps the energies of the electorate, Christian or otherwise. Be that as it may, Richard wants a certain baseline for Christian thought and practice with respect to political witness, in this or in any context. In ten theses:

The powers that be are always already at war with the kingdom of God.

The church, therefore, ought always to be on the side of God’s kingdom over against the kingdoms of this world.

It follows that the first and enduring political vocation of the church is prophetic criticism. Whatever else the church does, it begins and ends with the prophetic task.

Because the powers are fallen, our view of both the state and the arc of history should be deeply Augustinian: not tragic, but pessimistic. We are not going to bring heaven to earth, or establish God’s kingdom here and now, or proclaim peace in our time. Utopian dreams, including the Christian variety, are false and dangerous.

Because the powers are created, though, Christian pessimism need not write off the state altogether. This isn’t pure Anabaptism. Not only does the state have a divinely ordained role to maintain a modicum of peace and relative justice; Christians may—within limits, with modesty and caution—participate in and contribute to governance and other forms of political action in the wider society.

Such modest involvement does not lead to Christendom, however. Christendom is a dead end, precisely because it is not pessimistic enough about either the powers or the perduring sinfulness of Christian communities, projects, and institutions.

Together, these commitments repudiate any and all nostalgia for or attempts to “reclaim” a lost Christian past, pristine in innocence or even supposedly preferable to the present. Whatever one thinks of the middle ages, they aren’t coming back and Christians in America should not try to resuscitate an erstwhile medieval order. Stop working toward your imagined American Christian Commonwealth. Not only is it not happening (being a fool’s errand), it’s not worth the effort: it’ll blow up in your face like all the other attempts.

In a word, Christian politics should begin wherever we are, not in some other time or place where we most decidedly are not. Given the Augustinianism (or Pascalianism) of the foregoing, then, there is no One Right Way for Christians to approach politics. It’s piecemeal personal discernment all the way down, based on context, temperament, local conditions, prayer, opportunity, and other similar factors. Some Christians in the U.S. will “get involved”; others won’t. Realists will vote, march, and advocate, thereby getting their hands dirty; radicals will find themselves unable to do so. Neither is right or wrong. It’s a matter of prudence. We should stop duking it out to see who’s the victor between the Augustine of Niebuhr and the Yoder of Hauerwas.

The political challenge for American Christians today is thus an odd one: emotional disengagement via recalibration. American Christians have to find a way to stop caring so much, to stop finding their identity in politics, to stop investing the totality of themselves in winning or losing the latest (existential) political fight. Even if this borders on the impossible, it’s what’s called for in our situation.

To illustrate the point, suppose Christians in America stepped away from politics entirely for the next decade. From 2023 to 2033, no one in this country heard from a single Christian about political matters. A ten-year silence from the church. Christians kept living their lives, going about their business, seeking to be faithful, following the Lord—but without commentary of any kind (personal, public, digital, media, pulpit) on political affairs. Richard asks: “Do you think this ten year season would improve the church? Would this season improve the church internally, helping us conform more fully to the image of Jesus and more deeply into the kingdom of God, and externally, in how the world might perceive us?” He believes the answer is yes. The church needs a political detox, and it would be good for all involved.

I hope I’ve done Richard justice. Let me make one major point before I try to unpack a few more minute ones.

I take my original challenge to be this: Democracy is a genuinely new challenge for Christian political thought, because democratic involvement makes comprehensive demands of citizens. Self-governance is an exacting affair. Even prior to matters of identity, democratic action has the potential to be all-consuming. Because it is the business of life, our common life, it soaks up the whole of one’s attention, energy, and emotion. The most successful democratic movements in American history never could have happened if their adherents had been half-invested. Richard makes this observation a premise of his response, rather than a point of disagreement. The upshot as I see it, then, is twofold.

On one hand, it seems to be the case that democracy is a problem for Christian discipleship. Democracy wants your soul. But no servant can serve two masters. So how can politically engaged Christians also be disciples of Christ alone? I’m far from the first person to ask this question. Roman Catholic political thought has had anxieties on this score for two centuries and more. But it’s worth highlighting outright because it’s something of a taboo for American Christians to see democracy per se as a problem. To say it is a problem is not to say it should be dismantled or replaced. Only that it shouldn’t be assumed to be unproblematic from a Christian perspective.

On the other hand, Richard’s series left me thinking that we find ourselves where we started (or so it feels to me): that is, with the BenOp. Or in Richard’s words, from a post written six years ago, a progressive version of the Benedict Option. But the overall picture is the same. The American imperium is at odds with Christian witness. Don’t make the error of shoring up the imperium, much less mistaking shoring it up for the mission of the church. Instead, withdraw your heart, mind, voice, and labor to what is before you: the local congregation in its surrounding community. Attend to that. Think little, as Wendell Berry puts it. Stop thinking big; stop selling your soul to politics, only to be shown a fool for the umpteenth time.

In my view, this is where Richard lands: at a theologically orthodox, socially progressive version of the Benedict Option. A soft Anabaptism that doesn’t scream Nein! to politics so much as ignore it with a shrug before turning to love one’s neighbor—whose face and name one knows, living as one does in a flesh-and-blood neighborhood, not on Fox News or CNN or Twitter or TikTok.

I think this is wise counsel. For individual believers, I think it’s good advice, and especially for those most in need of a detox, i.e., folks who can tell you in detail what happened yesterday in D.C. but not the names of a neighbor in any direction, or the problems facing the city they actually live in.

So that’s that. Now let me turn to some larger thematic or architectonic matters that Richard’s series raised and about which I think we disagree.

First, while the “ten years of silence” proposition is an instructive thought experiment, I don’t think it works on its own terms. What it reveals, after reflection, is how it is impossible to live as a Christian without doing politics. For example, there are a lot of school-age children in Abilene (where Richard and I live) who are homeless. Christians here rightly see this as a pressing problem that calls for their involvement. But issues like family breakdown, poverty, nutrition, abuse, schooling, and homelessness are all political matters. Christians can’t be part of the solution if they forswear politics. Moreover, the call for silence overlooks the fact that speech is a part of action, indeed is a form of action. “I have a dream” is far more than a set of words. It’s a public political performance. It’s a world-shaping deed, expressed verbally. Words get things done. We know this from the Bible. That’s what prophecy is! Words that do things, words that make things happen. In short, Christians can’t follow Christ without doing or speaking about politics. That means ten years of silence is a nonstarter—even if we all (as I do) understand what Richard has in mind.