Resident Theologian

About the Blog

Jenson on catechesis for our time

Excerpts from a 1999 essay by Robert Jenson on catechesis for our time.

I’ve done my best to read everything Robert Jenson ever wrote, but he was so prolific that I regularly stumble onto something I’ve never seen before (or, at least, have no memory of reading). The latest is an essay on catechesis.

It comes from a 1999 volume that Jenson and Carl Braaten co-edited, titled Marks of the Body of Christ. It consists of essays by a wide range of ecumenical scholars on Luther’s so-called seven marks of the church: the word of God, the sacraments, the office of the keys, the pastoral office, the holy cross, and the liturgy. The volume interprets the cross as discipleship and the liturgy as catechesis, since Luther uses the latter term to pick out the Creed, the Decalogue, and the Lord’s Prayer as central to the church’s public worship of God.

Jenson’s essay is called “Catechesis for Our Time.” It’s a barnburner. If I could, I would republish the entirety below. Since I can’t, I’ll limit myself to quoting some of the juiciest excerpts.

Jenson, for readers unfamiliar with him, was born in 1930 and died in 2017. He was a polymath, a Midwesterner, a Lutheran, and German-trained. He was deeply involved in international ecumenical dialogues throughout his career and taught at a variety of institutions. He remained an ordained Lutheran all his life, but was deeply catholic in piety, liturgy, doctrine, and ecclesial sensibility. He was an astute observer of late modern culture in all its permutations and depredations.

Here’s how the essay begins:

I began teaching in 1955, in a liberal arts college of the church. My students were mostly fresh from active participation in their home town Protestant congregations. In those days, I and others like me regarded it as our duty, precisely for the sake of students’ faith, to loosen them up a bit. They had been drilled in standard doctrine — Jesus is the Son of God, God is triune but what that means is a mystery, heaven is the reward of a good life — to the point of insensibility to the gospel itself.

In 1966 I left undergraduate teaching. Then just 23 years later, I returned to teach at a similar churchly liberal arts college. My students were again mostly fresh from active participation in Protestant congregations — though now with more Catholics mixed in. During those years, the situation exactly reversed itself.

It is now my duty to inform these young Christians that, e.g., there once was a man named Abraham who had an interesting life, that then there was Moses and that he came before Jesus, that Jesus was a Jew who is thought by some to be risen from the dead, that there are commandments claiming to be from God, and that they frown on fornication and such, and other like matters.

Well hello there, shock of recognition. It’s always good to be reminded that Protestant liberalism comes for everyone; evangelicals are not immune, they just lag the mainline by a couple generations.

Jenson comments on the development of the catechumenate and the logic that lay behind it. He writes:

[Following the initial apostolic generations] the church needed and was granted institutions that could sustain her faithfulness within continuing history. So the canon of Scripture emerged, and the episcopate in local succession, and creeds and rules of faith. And so also an instructional institution arose, situated between conversion and baptism.

For it was the experience of the church, after a bit of time had passed in which to have experience, that baptism and subsequent life in the liturgical and moral life of the church, if granted immediately upon hearing and affirming the gospel, were too great a shock for spiritual health. Life in the church was just too different from life out of the church, for people to tolerate the transfer without some preparation.

Converts were used to religious cults that had little moral content, that centered often on bloody sacrifice, and that were oriented — as we might now put it — to the “religious needs” of the worshiper. They were entering a cult oriented not to their religious needs but to the mandates of a particular and highly opinionated God. They were entering a cult centered around an unbloody and therefore nearly incomprehensible sacrifice. And most disorienting of all, they were entering a cult that made explicit moral demands. They needed to be coached and rehearsed in all that, if their conversion was to be sustainable.

Catechesis therefore involves a comprehensive instruction in three areas of life: worship, ethics, and doctrine. Here’s how Jenson puts it:

Thus they needed to study, for a first thing, liturgics, that is, how to do these Christian things, so different from what could appeal to their existing habits and tastes. And they needed to be instructed in how to understand what they were doing.

And then there were those moral demands. Christian heads of household were not supposed to treat their wives as subjects, and both husband and wife were supposed to be sexually faithful — for converts from late-antique society such puritanism was a shocking violation of nature. More amazingly yet, Christian parents did not get rid of inconvenient children, not even of unborn ones. The list went on and on of things that converts’ previous society regarded as rights, that the church regarded as sins. If converts were to stand up under all these infringements on their personal pursuits of happiness, they needed some time under the care of moral instructors and indeed of watchful moral disciplinarians.

And then there were those creeds and doctrines. New converts were used to religions with little specificity, and so with little intellectual content. You were expected to worship Osiris in Egypt and the Great Mother in Asia Minor and Dionysus in Greece, and all of them and a hundred others simultaneously in Rome, and if the theologies of these deities could not all be simultaneously true, no matter, since you were not anyway expected to take their myths seriously as knowledge. For a relatively trivial but historically pivotal case: Did you have to think that the notorious lunatic Caligula was in fact divine? Not really, just so long as you burnt the pinch of incense.

But with the Lord, the Father of Jesus, things were different. He insisted that you worship him exclusively or not at all. And that imposed a cognitive task: if you were to worship the Lord exclusively, you had to know who he is, you had to make identifying statements about him and intend these as statements of fact. You had to learn that in the same history occupied by Caesar or Alexander, the Lord had led Israel from Egypt and what that meant for the world. You had to learn that in the same history occupied by Tiberius one of his deputies had crucified an Israelite named Jesus and what that in sheer bloody fact meant for the world. You had to learn that this Jesus was raised from the dead, and try to figure out where he might now be located. It was a terrible shock for the religious inclusivists and expressivists recruited from declining antiquity. There was a whole library of texts to be studied and conceptual distinctions to be made, if new converts were in the long run to resist their culturally ingrained inclusivism and relativism.

Catechesis was born as the instruction needed to bring people from their normal religious communities to an abnormal one. That is, it was born as liturgical rehearsal and interpretation, moral correction, and instruction in a specific theology. Apart from need for these things, it is not apparent that the church would have had to instruct at all.

One more excerpt, this time about what it means for the church to catechize the baptized for liturgical participation in a post-Christendom cultural context, in light of the temptation to water down or eliminate what makes her worship unique, which is to say, Christian:

Instead of perverting her essential rites, the church must catechize. She must rehearse her would-be members in the liturgies, fake them through them step by step, showing how the bits hang together, and teaching them how to say or sing or dance them. And she must show them wherein these rites are blessings and not legal impositions.

Nor does it stop with the minimal mandates of Scripture. The church, like every living community, has her own interior culture, built up during the centuries of her history. That is, the acts of proclamation and baptism and eucharist are in fact embedded in a continuous tradition of ritual and diction and music and iconography and interpretation, which constitutes a churchly culture in fact thicker and more specific than any national or ethnic culture.

Now of course this tradition might have been different than it is. If the church’s first missionary successes had taken her more south than west, her music and architecture and diction and so on would surely have developed differently. And in the next century, when the center of the church’s life will probably indeed be south of its original concentration, the church’s culture will continue to develop, and in ways that cannot now be predicted. But within Christianity, what might have been is beside the point; contingency is for Christianity the very principle of meaning; it is what in fact has happened — that might not have happened — that is God’s history with us, and so the very reality of God and of us.

We are not, therefore, permitted simply to shuck off chant and chorale, or the crucifix, or architecture that encloses us in biblical story, or ministerial clothing that recalls that of ancient Rome and Constantinople, or so on and on. Would-be participants will indeed find some of this off-putting; people will indeed drift into our services, not grasp the proceedings, and drift out again. We will be tempted to respond by dressing in t-shirts and hiring an almost-rock group — not, of course, a real one — and getting rid of the grim crucifixes. Then we will indeed need less catechesis to adapt would-be participants to the church, because we will be much less church. If instead we are aware of the mission, and of the mission’s situation in our particular time, we will not try to adapt the church’s culture to seekers, but seekers to the church’s culture.

So, for an only apparently trivial example, it is almost universally thought that children must be taught childish songs, with which occasionally to interrupt the service and serenade their parents. They are not, it is supposed, up to the church’s hymns and chants. The exact opposite is the truth, and in any case the necessity. In my dim youth rash congregational officials once hired me to supervise the music program of a summer church school. I taught the children the ditties supplied me, but also some plain chant. When in the last days, I asked the children what they wanted to sing, it was always the plain chant.

Catechesis for our time, as the culture of the world and the culture of the church go separate ways, will be music training and art appreciation and language instruction, for the church’s music and art and in the language of Canaan. If we do not do such things, and with passionate intention, the church will be ever more bereft of her own interior culture and just so become ever more the mere chaplaincy of the world’s culture. The recommendations of the “church growth” movement will indeed produce growth, but not of the church.

My latest: on holy orders

A link to and brief description of my latest publication, an article on the sacrament of holy orders.

I’ve got an article in the latest issue of the Journal of Christian Studies. The theme of the issue is “Ministry and Ordination.” The editor, Keith Stanglin (a mensch, if you don’t know him), commissioned pieces from scholars that represent or argue for a position not found in, or at least exemplified by, their own tradition. So, for example, the article after mine is by a Roman Catholic on the priesthood of all believers. Whereas mine is called “The Fittingness of Holy Orders.” It presents just that.

The article was a pleasure to write. It scratched an itch I didn’t know I had. Its guiding lights are Robert Jenson and Michael Ramsey. And it opens with twenty theses—I call them “escalating propositions”— on the sacrament of holy orders that ramp up from the basic notion of some formal leadership in the church all the way to full episcopal-dogmatic-eucharistic-apostolic succession.

Subscribe to the journal (or ask your library to). If you want a PDF of my article, email me and I’ll send you a copy.

Biblical critical theory

A link to my review essay of Christopher Watkin’s new book Biblical Critical Theory.

This morning Comment published my long review essay of Christopher Watkin’s new book Biblical Critical Theory. Here’s a bit about him and the book from the review:

Watkin is a scholar of modern and postmodern French and German philosophy. He has written a number of studies on major contemporary theorists like Derrida, Foucault, Deleuze, and Serres. He earned his doctorate at Cambridge and teaches in Melbourne. This is not his first book for a popular audience, but it is certainly his biggest and boldest. Running more than six hundred pages and spanning the entire biblical narrative, the book closely follows the Augustinian blueprint. Watkin wrote the work he sought but couldn’t find in the library stacks: a biblical critical theory, in careful conversation with and counterpoint to the variety of secular critical theories on offer. Each of the scholars I mentioned above (MacIntyre et al.) is catholic in one form or another. Watkin saw this gap in the literature: an evangelical Protestant meta-response to (post)modernity. So he took up the task himself.

As I explain in detail in the review, I don’t think the book succeeds. Read on to find out why.

It’s always a pleasure to write for Comment. Thanks to Brian Dijkema and Jeff Reimer for ever-reliable editorial wisdom, and to unnamed friends who made the argument stronger in the drafting stage.

You can’t die for a question

A follow-up reflection on biblicism, catholicity, martyrdom, and perspicuity.

I had some friends from quite different backgrounds do a bit of interrogation yesterday, following my post about biblicist versus catholic Christianity. Interrogation of me, that is. As is my wont, I sermonize and then qualify, or at least explain. Yesterday was the sermon. Today is the asterisk.

1. What I wrote has to do with a persistent conundrum I find myself utterly unable to solve. I cannot grasp either of two types of Christianity. The first lingers most in yesterday’s post. It is a form of the faith that never, ever grows; never, ever settles; never, ever stabilizes; never, ever knows. Its peculiar habit, rather, is always and perpetually to pull up stakes and go back to the beginning; to return to Go; to start from scratch; to question everything and, almost on purpose, to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Am I exaggerating? I’m not! Primitivist biblicism, rooted in nuda scriptura, affirms on principle that every tradition and all Christians, from the apostles to the present, not only may have gotten this or that wrong but did in fact get just about everything wrong. And this affirmation inexorably eats itself. For what the biblicist proposed yesterday is bound to be wrong tomorrow—that is, discovered by some other enterprising biblicist to belong to the catalogue of errors that is Christian history.

At the same time, this ouroborotic style of Christianity affirms a second principle: namely, the total sufficiency and perfect perspicuity of the canon. Come again? Didn’t we just say that everyone who’s ever read it got it wrong, until you/me? Indeed. Not only this, but the excavationist-reader of the clear-and-sufficient text somehow misses the fact that he is himself doing the very thing he chides the tradition for doing: namely, interpreting what requires no interpretation. The one thing we may be sure of is that his successor, following the example of his predecessor with perfect consistency, will fault him for his interpretation, while offering an alternative interpretation.

This whole dialectic makes me crazy. As evidenced by yesterday’s vim and vigor.

2. Let me put it this way. I understand that there are both people and traditions that embody this dialectic, that don’t see anything wrong with it. What I can’t understand is pastors and scholars wanting to produce such a viewpoint as a desirable consequence of ecclesial and academic formation. My goal as a teacher is to educate my students out of this way of thinking. Why would we want to educate them into it?

I will withhold comment on whether Protestantism as such is unavoidably ouroborotic. At the very least, we may say that the ouroborotic impulse is contained within it. Reformation breeds reformation; revolution begets revolution. Semper reformanda unmasks error after error, century after century, until you find yourself with the apostles, reforming them, too. And the prophets. And Jesus himself. And the texts that give you him. And the traditions underlying those texts. And the hypothetical traditions underlying those.

And all of a sudden, you find there’s nothing left.

Again, I’m not indicting Protestants per se. But there is an instinct here, a pressure, a logic that unfolds itself. And there are evangelical traditions that actively nurture it in their people. I’ve seen it my whole life. It’s not good, y’all! I, the ordinary believer, come to see myself, not as a recipient of Christian faith, but as its co-constructor, even its builder. It’s up to me:

Brad the Believer!

Can he build it?

Yes he can!

Can he fix it?

Yes he can!

And how do I do it? By reading the Bible, alone with myself, at best with a few others—albeit with final say reserved for me.

The faith here becomes a matter of arguing my way to a conclusion, rather than yielding, surrendering, and submitting to a teaching. Cartesian Christianity is DIY faith. It cannot sustain itself. It’s built for collapse. (The call is coming from inside the house.)

3. The second type of Christianity to which I alluded above, which was less visible in the post yesterday, is not so much a species of biblicism as its repudiation. In the past I’ve called it post-biblicism biblicism, though it doesn’t always entail further biblicism. A friend commented that what we need is an account of progressive biblicism, though that’s not what I have in mind either. What I have in mind is, I suppose, what I’ll call know-nothing Christianity. A Christianity of nothing but doubts. A faith reducible to questions.

I take it as given that I’m not talking about asking questions or having doubts, much less mysticism or apophatic spirituality. (Go read Denys Turner. All theology is apophatic, rightly understood.) No, I’m talking about a Christianity that has lost the confidence of the martyrs, the boldness of the apostles, the devotion of the saints.

Put it this way. When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die. But you can’t die for a question. Christianity is a religion of proclamation. It preaches a message. It announces tidings. It does not say, “Jesus might have been raised from the dead.” It says, “Jesus is risen.” You or I may well have intrusive mights in our struggles with faith. But the church is not a community of might and maybe. The church is a community of is, because she is a people of resurrection. What began in an empty tomb, she confesses, will be consummated before the whole world at the risen Lord’s return.

That’s something to die for. And therefore to live for. I can neither die nor live for a question mark. The church speaks with periods and exclamation points. She errs—her pastors miss the mark—when the faith is reduced to nothing but ellipses and questions.

4. It’s true that I exaggerated the catholic style of magisterial Protestantism. I also may have made it sound as though Christianity never changes; that whatever Christians have always said and done, they are bound always to say and do in the future, till kingdom come. (Though I think if you re-read what I wrote, I couched enough to give the Prots some wiggle room.)

In any case: granted. Preacher’s gonna preach. But here’s what I was getting at.

Christianity simply cannot be lived if, at any moment, any and every doctrine and belief, no matter how central or venerable, lies under constant threat of revision and removal. All the more so if the potential revision and removal are actions open to any baptized believer. Ouroborotic faith comes to seem a sort of vulgar Kantianism (or is it that Kant is vulgar Lutheranism?): heteronomy must give way to autonomy, lest the faith not be authentic, real, mine. The word from without becomes a word from within. The word of the gospel transmutes into a word I make, am responsible for making. I am a law unto myself; I am the gospel unto myself.

Who can live this way? Who can give themselves to a community for a lifetime based on a message (a book, a doctrine, an ethics) subject to continuous active reappraisal? and reappraisal precisely from below? The faith becomes a kind of democracy: a democracy of the living alone, to the exclusion of the dead. And just like any democracy, what’s voted on today will be up for debate tomorrow.

In a word: If Christianity is nothing but what we make of it—an ongoing, unfinished construction project in which nothing is fixed and everything, in principle, is subject to renovation and even demolition—then we are of all men most miserable.

To be sure, the skeptic and the atheist will see this statement as a précis of their unbelief. What beggars my belief is that, apparently, there are self-identified Christians who not only affirm it, but actively induce it in the young, in college students, in laypeople. I cannot fathom such a view.

5. A final thought. I am a student, in different ways, of two very different theologians: Robert Jenson and Kathryn Tanner. Much of what I’ve outlined here goes against what both of them teach regarding the church and tradition; or at least it seems to. Let me say something about that.

I am thinking of the opening two chapters of Jenson’s Systematics and of the whole normative case Tanner makes in Theories of Culture. In the latter, Tanner takes issue with both correlationists (to her “left”) and postliberals (to her “right”) regarding what “culture” is, how the church inhabits and engages it, and the honest picture that results for Christian tradition. There is a strong constructivist undercurrent in the book that would push back against what I’ve written here.

As for Jenson, he argues that the church is a community defined by a message. Tradition is the handing-on of the message, both in real time (from one person/community to another) and across time (from one generation to another). It is not a bug that causes the gospel to “change” in the process of being handed on. It’s a feature. We see this transmission-cum-translation project already in the New Testament. And it necessarily continues so long as the church is around, handing on the gospel anew.

Why? Because new questions arise, in the course of the church’s mission, questions that have not always been answered in advance. Sometimes it isn’t questions at all, but cultural translation itself. How should the gospel be incarnated here, in this place? Among gentiles, not Jews? Among rulers, not peasants? Among Ethiopians, not Greeks? Among polytheists, not monotheists? Among atheists, not polytheists? Among polygamists, not monogamists? Among liberals, not conservatives? Among capitalists, not socialists? Among democrats, not monarchists? In an age of CRISPR and cloning, not factories and the cotton gin? In a time when women are no longer homemakers only, but landowners, degree-holders, and professionals? When men are in offices and online and not only in fields and mines?

The gospel, Jenson says, doesn’t change in these settings. But how the church says the gospel, in and to such settings, does change. How could it not? We don’t speak the gospel in the same words as the apostles, or else we’d be speaking Aramaic and Greek; we’d be talking about idol meat and temple prostitutes and incense to Caesar and Artemis the Great. Now, we do talk about such things. But not as matters of living interest to our hearers. As, rather, samples of faithful gospel speech from the apostles, samples that call for our imitation, extension, and application. We say the selfsame gospel anew in diverse contexts, based on the apostolic example, in imitation of their model. As Barth says in the Church Dogmatics, theology is not a matter of repeating what the apostles and prophets said, but of saying what must be said here and now on the basis of what they said there and then.

In this way, “evangelical” tradition is simultaneously unchanging, fixed, stable and fluid, organic, growing. It’s why, as a friend once said after reading Theories of Culture, the church possesses a teaching office. Magisterial authority of some sort is necessary in a missionary community defined by a historical message expressed in written documents. Someone’s got to do the interpreting, not least when questions arise that the apostles neither answered nor even foresaw.

Hence my roping the magisterial Protestants into the “catholic” version of Christianity. Try as they might, they cannot deny that the doctrine of the Trinity formulated and codified by Nicaea and Constantinople is dogma for the church. It is irreversible, irrevocable, and therefore irreformable. Semper reformanda does not apply here. (And if not here, then not elsewhere, too.) Not because the Bible is crystal clear on the subject. Not because trinitarian doctrine is laid out in so many words on the sacred page. Not because no reasonable person could read the Bible differently.

No: It is because the church’s ancient teachers, faced with the question of Christ and the Spirit, read the Bible in this way, and staked the future of the faith on it; and because we, their children in the faith, receive their decision as the Spirit’s own. It seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us… It is thus neither your job nor mine to second guess it, to search the Bible to confirm that Saint Athanasius et al did, in fact, get the Trinity right. It’s our job to accept it; to confess it; to believe it. Any other suggestion misunderstands my, our, relationship to the church and to her tradition.

6. A final-final thought; a conclusion to my conclusion.

In my graduate studies I came to be deeply impressed by the underdetermined character of Scripture. The text can reasonably be read by equally reasonable people in equally reasonable ways. “Underdetermined” is Stephen Fowl’s word. It doesn’t mean indeterminate. But neither does it mean determinate. Christian Smith calls the result “PIP”: pervasive interpretive pluralism. Smith is right. His point is downstream from the hermeneutical, though, which is downstream in turn from the theological and ecclesiological point.

I’ve tried to unpack and to argue that point in my two books: The Doctrine of Scripture and The Church’s Book. Together they’re just short of 250,000 words. I wouldn’t force that much reading (of anyone, certainly not of me!) on anybody. Nor can I summarize here what I lay out there. I simply mean to draw attention to a fundamental premise that animates all of my thinking about the Bible and thus about the church, tradition, and dogma. That premise is a rejection of a strong account of biblical perspicuity. On its face, the Bible can be read many ways; rare is any of these ways obvious, even to the baptized. If I’m right, then either the Bible can never finally be understood with confidence (a position I reject, though I have learned much from scholars who believe this) or we ordinary Christians stand under that which has been authorized by Christ, through his Spirit, to teach the Bible’s word with confidence, indeed with divine assurance. Call the authority in question the church, tradition, ecumenical councils, bishops, magisterium—whatever—but it’s necessary for the Christian life. It’s necessary for Christianity to work. And not only necessary. But instituted by Christ himself, for our benefit. For our life among the nations. For our faith, seeking understanding as it always is. For our discipleship.

We are called to live and die for Christ. The church gives us Christ. She does not give us a question. She gives us a person. In her we find him. If we can’t trust her, we can’t have him—much less die for him. They’re a package deal. Accept both or neither. But you can’t have one without the other.

A blurb, a reply, a review

Some links: an endorsement of a posthumous Jenson book; a reply to Radner and Trueman; a review of Jamieson and Wittman.

A quick link round-up.

First, I neglected to mention the publication, earlier this spring, of a posthumous work by Robert Jenson titled The Trinity and the Spirit: Two Essays from Christian Dogmatics. Almost forty years ago Jenson collaborated on a remarkable multivolume work called Christian Dogmatics, coauthored with his fellow Lutherans Carl Braaten, Gerhard Forde, Philip Hefner, Paul Sponheim, and Hans Schwartz. The folks at Fortress pulled out Jenson’s contributions to that work and made a book out of them. My endorsement is on the back cover (alongside Bruce Marshall’s); here’s the full blurb:

Robert Jenson's contribution to the multi-authored Christian Dogmatics in the early 1980s has always been the most underrated part of his corpus, for the simple reason that few readers ever happened upon it. This stand-alone republication is therefore a gift to all readers of Jenson, whether seasoned veterans or those new to this great American theologian. The whole work is worthy of one's attention, but the section on the Holy Spirit is alone worth the price of the book. The ongoing reception of Jenson's thought will be bolstered by having his full pneumatology ready to hand, and the church will be edified once more by a pastor, scholar, and doctor of the sacred page whose love for the Lord and for his bride suffused all that he said and did, to the very end of his life.

What are you waiting for? Go buy the book!

Second: In the latest issue of First Things, both Ephraim Radner and Carl Trueman have written letters responding to my essay two issues ago on “Theology in Division.” The letters are generous and thoughtful. I do my best to reply in kind.

Third: My review of R. B. Jamieson and Tyler R. Wittman’s Biblical Reasoning: Christological and Trinitarian Rules for Exegesis in the International Journal of Systematic Theology is available to read in an early online version. Here’s the money graf:

The book is a triumph. It is a work of rich scholarship that remains accessible, stylishly written, spiritually nourishing, even devotional, while offering useful practical guidance for serious readers to avoid error and seek the living God in Holy Scripture. It does so not only by talking about the text but by exegeting it, with attentive care, on just about every page. One can only hope this book will become assigned reading in seminaries until such time as historical criticism releases its chokehold on the hermeneutical imaginations of pastors and scholars alike.

That comes about halfway through the review. I do raise some critical questions later, but this summary judgment is the relevant takeaway. Another book for you to buy.

Speaking of which. A friend alerted me to the fact that my second book—The Church’s Book: Theology of Scripture in Ecclesial Context—is available on Amazon for under $17. It’s usually $50! Nab a copy while it’s cheap, y’all! Bundle it with Wittman/Jamieson and Jenson. Come to think of it, that trifecta wouldn’t be unfitting…

I’m in First Things + on a podcast

Links to a new essay in the latest issue of First Things and an interview on a new podcast called The Great Tradition.

An essay of mine called “Theology in Division” is in the new issue of First Things. Here’s a link. I’ve had something like it half-written in the back of my mind for the last five years. I’m glad for it to be in print finally. I’m also glad for it to honor both Robert Jenson and Joseph Ratzinger, two theologians whose legacy I treasure who have now gone on to their reward.

I’m also on the latest episode of a new podcast called The Great Tradition. We recorded the interview back in December. It’s about the Bible. This time I’ve got a good mic, so I don’t sound like I’ve yelling through feedback the whole time.

After declining invitations to appear on podcasts for years, I’ve now been on 5-10 of them over the last 12+ months. My line used to be “Friends don’t let friends go on podcasts before tenure.” I have tenure now, so I guess I’m covered. In any case, I’ve come to enjoy the interviews. This one was fun, and I think we found a way to cover all the main theological issues raised by my two books on Scripture.

Jenson on metaphor and theological language

Across the two volumes of his systematic theology, Robert Jenson makes a number of comments about the nature of metaphor in theological speech. I tracked down one of these the other day, only to stumble across others. I thought I’d share them here.

Across the two volumes of his systematic theology, Robert Jenson makes a number of comments about the nature of metaphor in theological speech. I tracked down one of these the other day, only to stumble across others. I thought I’d share them here. Some are in the body of the text, some are footnotes; I’ll signal when which is which.

At the first mention, Jenson has just spent some paragraphs discussing the Old Testament’s description of the relationship between God and Israel, as well as between God and individual Israelites, “as a relation of father to son” (I:77). He then writes, “Given that such language is indeed used, we should not too quickly interpret it as a trope.” To which is appended the footnote (n.20):

That is, “. . . is a Son of God” is used in these passages as a proper concept. If someone has a theory of “metaphor” such that the use can be both concept and metaphor, well and good.

Clearly, Jenson has certain theories of metaphor in mind. We see in the next chapter whose these are. As he writes (I:104):

When the bishops and other teachers left Nicea and realized that, along with condemning Arius, they had renounced the established subordinationist consensus, many began to backtrack. Indeed, refusal to face Nicea has remained a permanent feature of Christianity’s history. If modalism has been the perennial theology of the pious but unthinking, Arianism has continually reappeared in the opposite role, as the theology of those controlled more by culture’s intellectual fashion than by the gospel.

He then adds in a footnote (n.99):

Most blatantly in recent memory, the “theology of metaphor,” paradigmatically represented by Sallie McFague, Metaphorical Theology: Models of God in Religious Language (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1982).

The culprit at last! Nor is she, or theories like hers, far from Jenson’s mind in the next volume. Three chapters in, he is writing of “the sheer musicality” of “the divine conversation”; he argues that “to be a creature is to belong to the counterpoint and harmony of the triune music” (II:39). Immediately he anticipates an objection:

The previous paragraph is likely to be read as metaphor, and indeed as metaphor run wild. It is not so intended, or not in any sense of “metaphor” that is alternative to “concept.” Such words as “harmony” are here conscripted to be metaphysically descriptive language more malleable to the gospel’s grasp of reality than is, for central contrary example, the language of “substance” in its native Aristotelian or Cartesian or Lockean senses. That we are used to the metaphysical concepts of Mediterranean pagan antiquity and its Enlightenment recrudescence does not mean they are the only ones possible; there is no a priori reason why, for example, “substance”—which after all simply meant “what holds something up”—should be apt for conscription into metaphysical service and, for example, “tune” should not.

On the second sentence he hangs a footnote (n.41):

This may be the place to insist on a vital point against most recent “metaphor” theology. Its practitioners want to have it both ways. Sometimes it is important for them to note that metaphor is a universal function in all language. This of course is a truism, and when we think of “metaphor” in this way, there is no opposition between “metaphor” and “concept.” But then the key step in their theological arguments is that they pit metaphor against concept: we have, they say, “only” metaphors for God. It is perhaps safe to say that what most theologians now have in mind when they speak of metaphor is trope that is not concept; it is for this reason that I am so leary of “metaphor.”

Later in the same volume the subject reappears one last time, in the opening to the chapter on the church’s polity (II:189-190):

In ecumenical ecclesiology it has become customary to discuss the church’s reality under three headings drawn from the New Testament: the church is the people of God, the temple of the Spirit, and the Body of Christ. The trinitarian echoes of the pattern are obvious, as must be its attractiveness to this enterprise.

But much twentieth-century theology has succumbed here also to an endemic strategy of evasion: “people,” “temple,” and “body” have been treated as unconnected “images” or “metaphors” of the church, which at most need to be balanced or variously emphasized, that is, which need not be taken seriously as concepts. But although “temple” may be a simile when applied to the church, which to be sure is not literally a building or place, “people” clearly is neither metaphor nor simile; and if one pauses to examine Paul’s actual use of the phrase “body of Christ,” it becomes obvious that neither is it.

If we are to follow this scheme, then it must be the task of systematic theology to take “The church is the people of God, the temple of the Spirit, and the body of Christ” with epistemic seriousness by displaying the conceptual links between these phrases.

In the second paragraph, after the word “emphasized,” Jenson attaches the following footnote (n.2):

It perhaps needs to be repeated in this volume: I am well aware of the sense in which all language may be said to be metaphorical in its origins. But this trivial obsession has recently been widely used to escape the necessary distinction in actual usage between concepts and tropes. Both concepts and tropes are “functions,” sentences with holes in them. A concept is a function that, if the hole is filled in, yields a sentence that can be a premise in valid argument. Thus “The church is the temple of the Spirit” is a properly metaphorical proposition precisely because it will not, together with “All temples are containers for a god or gods,” yield “The church is the container of a god.”

Jenson was always attentive to the nature of language and, in particular, to the linguistic turn in philosophy and theology. See his long footnote back in the first volume, incidentally in a chapter dedicated to God the Father, here following discussion of Jonathan Edwards and Immanuel Kant (I:120n.21):

The most notorious line of this line of work [that is, the postmodern deconstruction of the “Western notion and experience of the self”] begins, significantly, with a theory of language, the “structuralist” theory founded by Ferdinand de Saussure . . . . A “language,” in structuralist theory, is a system of signs, whether of words, gestures, or other cultural artifacts. Each such system functions as possible discourse merely by the internal relations of its constituent signs, independently of any relation to a world outside the system. A language system as such can therefore have no history. It simply perseveres for its time and then is replaced by another, built perhaps from its fragment-signs; a favorite term in this connection is bricolage, the assembling of a new structure from fragments of former structures.

“Poststructuralism” combines structuralist understanding of language with an ontological position widely held in late-modern Continental thought: the personal self is said to be constituted in and by language, to subsist only as the act of self-interpretation. The emblematic figure in this movement has been Jacques Derrida . . . . The combination undoes the self, for the human self, inescapably, does have history. If then the self is linguistic, constituted in self-interpretation, and if language’s history is discontinuous, then so is the self’s history; then the self is constituted only as an endless bricolage of succeeding self-interpretations. A human life can have no status as a whole; that is, there is no self.

There’s much more where that came from. For essays along this line, there are some great ones available online. For a whole book on the matter, consult The Knowledge of Things Hoped For: The Sense of Theological Discourse.

Reunion

Reading theology from the previous century has the power to trick you into thinking that reunion between the divided communions was, and remains, a live possibility. As late as 1999, when Robert Jenson published the second volume of his systematic theology, the bulk of which is a fulsome ecclesiology in close conversation with both Vatican II and the most recent ecumenical dialogues, you would be forgiven for getting the impression that reunion—between Rome and Wittenburg, between Rome and Canterbury, even between Rome and Constantinople—was conceivable within our lifetime, even right over the horizon.

Reading theology from the previous century has the power to trick you into thinking that reunion between the divided communions was, and remains, a live possibility. As late as 1999, when Robert Jenson published the second volume of his systematic theology, the bulk of which is a fulsome ecclesiology in close conversation with both Vatican II and the most recent ecumenical dialogues, you would be forgiven for getting the impression that reunion—between Rome and Wittenburg, between Rome and Canterbury, even between Rome and Constantinople—was conceivable within our lifetime, even right over the horizon.

More generally, reading about church division and the need for church unity on the page can make the matter seem rather simple, certainly from a low-church or Protestant perspective. It inevitably reduces the problem to disagreements over theology; accordingly, once those disagreements are resolved, unity becomes achievable.

To my readerly mind, it made the most sense that, if any communions were to reunite in our lifetime, it would be Rome and the East. After all, on the page, very little in terms of substantive theological disagreements obtain between them. (I can defend that claim another time!) On the page, Rome is willing to meet the East halfway—and then some. On the page, these things can be worked out. The unity of God’s people is at stake, after all! The very truth of Jesus’s prayer for his church in John 17!

On the page, all of this seems eminently plausible. Until, that is, you meet an actual, flesh-and-blood Orthodox Christian. Until you read an actual Orthodox writer who is neither American nor trained in American institutions. Until you visit an actual Orthodox country. Until you attend the Divine Liturgy or visit an Orthodox monastery.

And then it hits you. This is a pipe dream. Reunion between Rome and the East will never happen. Not ever. Not until the Lord’s return. Rome could meet the East 99% of the way, and the East would look at that 1% and say: Thanks, but no thanks. We’re good.

Perhaps that sounds hyperbolic. Or perhaps it sounds like I’m indicting the East or endorsing the West. That’s not at all what I mean, though. As David Bentley Hart wrote a few years back, Eastern Orthodoxy has always been skeptical of the ecumenical movement, for at least two reasons intrinsic to and coherent with its own teachings and history. The first is that ecumenism waters down the faith to a few core beliefs beyond which all else, especially liturgical form and sacred tradition, is adiaphora. In other words, ecumenism Protestantizes the faith. But if you think that Protestantism is wrong about the faith, why would you do that? The second reason is that the East does not believe the church is divided, or that it lacks the fullness of Christ’s promise to his one church. It does not believe, as Rome does, that it suffers a “wound.” Rather, the East believes wholeheartedly and without apology that it is and forever shall be the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church that Christ founded by his Spirit on Pentecost some two thousand years ago. It has kept the faith whole and entire; it has preserved the faith once for all delivered to the saints; it has not wavered; it has not broken; it has not failed. It cheerfully welcomes all, including schismatics and heretics (i.e., Romans and Protestants), to join its ranks. But it is unbroken, undivided, and complete. Ecumenism, on this view, is at once an affront, a contradiction, a threat, and a solvent to this crucial truth. To admit it, to engage it, to accept it, would be to deny the fact of Orthodoxy itself.

So, as I say, I’m not writing in critique of the East. I’m writing with a bird’s-eye view on the total matter of church unity, in global perspective. And after a century of optimism, things don’t look good. Despair is a sin, so we aren’t allowed that route. But it is hard to see, for me it is impossible to see, what it might mean to hope and work for the unity of the church across both the world and millennia-long divisions. For those divisions have become cultural, deeply ingrained in the folkways and forms of life that define distinct peoples, such as Greece or Russia. What would, what could, reunion mean for such people on the ground (and not on the page)? I have no answer.

Jenson, following Ratzinger, notes at the beginning of volume one of his systematics that theologians under conditions of ecclesial division can only write for the one church that God will, by his grace, someday bring about. He says further that such unity must be a work of the Spirit—and the Spirit may act tomorrow. I believe these words. I follow that vision. But I worry, sometimes, that they are merely marks on a page. For the letter kills; the Spirit gives life.

In a word, in the matter of our impossible division, we are reduced to prayer. So I pray:

How long, O Lord? How long will your people be separated one from another? Come, Spirit, come! Restore your people. Make them one as you are one. Hear our prayer, and hear your Son’s, on our behalf, and for his sake: Amen.

The bishop of Rome in Alpha Centauri

I finally read Walter M. Miller Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, a novel with my name written on it if ever there was one. It’s more than six decades old—having been written in the wake of World War II; its origins there, as well as the fate of its author, are shadowed with tragedy—so I’m not worried about spoiling it for you, but be it known that the following quote comes from the final 50 pages of the book.

I finally read Walter M. Miller Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, a novel with my name written on it if ever there was one. It’s more than six decades old—having been written in the wake of World War II; its origins there, as well as the fate of its author, are shadowed with tragedy—so I’m not worried about spoiling it for you, but be it known that the following quote comes from the final 50 pages of the book.

After humanity refuses to learn from its errors in the first nuclear holocaust of the late twentieth century, some two thousand years later they do it again, only this time with few survivors likely to see life beyond it. So the Church makes plans for human, and thus Christian, life beyond this planet. Here is the scene when an Abbot gives final instructions and blessings to a few dozen priests before they set sail for an interstellar voyage to a colony in another solar system:

It had not been easy to charter a plane for the flight to New Rome. Even harder was the task of winning clearance for the flight after the plane had been chartered. All civil aircraft had come under the jurisdiction of the military for the duration of the emergency, and a military clearance was required. It had been refused by the local ZDI. If Abbot Zerchi not been aware of the fact that a certain air marshal and a certain cardinal archbishop happened to be friends, the ostensible pilgrimage to New Rome by twenty-seven bookleggers with bindlestiffs might well have proceeded on shank's mare, for lack of permission to use rapid transport jet. By midafternoon, however, clearance had been granted. Abbot Zerchi boarded the plane briefly before takeoff-for last farewells.

“You are the continuity of the Order,” he told them. “With you goes the Memorabilia. With you also goes the apostolic succession, and, perhaps—the Chair of Peter.

“No, no,” he added in response to the murmur of surprise from the monks. “Not His Holiness. I had not told you this before, but if the worst comes on Earth, the College of Cardinals—or what's left of it—will convene. The Centaurus Colony may then be declared a separate patriarchate, with full patriarchal jurisdiction going to the cardinal who will accompany you. If the scourge falls on us here, to him, then, will go the Patrimony of Peter. For though life on Earth may be destroyed—God forbid—as long as Man lives elsewhere, the office of Peter cannot be destroyed. There are many who think that if the curse falls on Earth, the papacy would pass to him by the principle of Epikeia if there were no survivors here. But that is not your direct concern, brothers, sons, although you will be subject to your patriarch under special vows as those which bind the Jesuits to the Pope.

“You will be years in space. The ship will be your monastery. After the patriarchal see is established at the Centaurus Colony, you will establish there a mother house of the Visitationist Friars of the Order of Saint Leibowitz of Tycho. But the ship will remain in your hands, and the Memorabilia. If civilization, or a vestige of it, can maintain itself on Centaurus, you will send missions to the other colony worlds, and perhaps eventually to the colonies of their colonies. Wherever Man goes, you and your successors will go. And with you, the records and remembrances of four thousand years and more. Some of you, or those to come after you, will be mendicants and wanderers, teaching the chronicles of Earth and the canticles of the Crucified to the peoples and the cultures that may grow out of the colony groups. For some may forget. Some may be lost for a time from the Faith. Teach them, and receive into the Order those among them who are called. Pass on to them the continuity. Be for Man the memory of Earth and Origin. Remember this Earth. Never forget her, but—never come back.” Zerchi's voice went hoarse and low. “If you ever come back, you might meet the Archangel at the east end of Earth, guarding her passes with a sword of flame. I feel it. Space is your home hereafter. It's a lonelier desert than ours. God bless you, and pray for us.”

He moved slowly down the aisle, pausing at each seat to bless and embrace before he left the plane. The plane taxied onto the runway and roared aloft. He watched until it disappeared from view in the evening sky. Afterward, he drove back to the abbey and to the remainder of his flock. While aboard the plane, he had spoken as if the destiny of Brother Joshua's group were as clear-cut as the prayers prescribed for tomorrow's Office; but both he and they knew that he had only been reading the palm of a plan, had been describing a hope and not a certainty. For Brother Joshua's group had only begun the first short lap of a long and doubtful journey, a new Exodus from Egypt under the auspices of a God who must surely be very weary of the race of Man.

Those who stayed behind had the easier part. Theirs was but to wait for the end and pray that it would not come.

This excerpt provides a lovely sample of Miller’s fine grasp of both Christian theology and ecclesiastical language, without losing the heart of it all. The whole book is quite beautiful. I can’t believe it took me this long to read it.

As I got to this part—what is in effect a short story or novella contained in a larger set of stories spanning 1,500 years or so—it reminded me of Robert Jenson’s discussion of the papacy in the second volume of his systematic theology, published in 1999. I seemed to recall Jenson coming to the very question of whether the pope might continue the office of the bishop of Rome elsewhere than Rome, including elsewhere than earth. Here’s the passage:

Two matters remain . . . . The first is a question so far skirted: Granted that there must be a universal pastorate, why should it be located in Rome? Why not, for example, Jerusalem? The question is odd, since Roman primacy developed first and the theology thereof afterward. But it nevertheless must be faced.

Pragmatic reasons are not hard to find, and the dialogues have gone far with them. So international Catholic-Anglican dialogue: it occurred “early in the history of the church” that to serve communion between local diocesan churches “a function of oversight . . . was assigned to bishops of prominent sees.” And within this system of metropolitan and patriarchal sees, “the see of Rome . . . became the principal center in matters concerning the church universal.” And so finally: “The only see which makes any claim to universal primacy and which has exercised and still exercises episcope is the see of Rome, the city were Peter and Paul died. It seems appropriate [emphasis added] that in any future union a universal primacy . . . should be held by that see.”

It is clear that the unity of the church cannot in fact now be restored except with a universal pastor located at Rome. And this is already sufficient reason to say that churches now not in communion with the church of Rome are very severely “wounded.” Just so it is sufficient reason to say also that the restoration of those churches’ communion with Rome is the peremptory will of God. Yet such considerations do not provide quite the sort of legitimation we look for in systematic theology and that we found for the episcopate and for the universal pastorate simply as such.

The historically initiating understanding of Roman primacy is perhaps itself the closest available approach to what is wanted. For in the earlier centuries of the undivided church, it was precisely the local church of Rome, and not the Roman bishop personally, that enjoyed unique prestige. The bishop of Rome enjoyed special authority among the bishops because their communion with him was the necessary sign of their churches’ communion with the church of that place. If the pope's universal pastorate is based on a unique prestige of the Roman congregation, then obviously in Rome is where it must be exercised.

In the fathers’ understanding of the apostolic foundation of the church, the founding history of each apostolic local church was a different act of the Spirit. This act was thought to live on in a special character of that church, in what one might perhaps call a continuing communal charism: the continuing life of each apostolically founded church was experienced as an enduring representation of her role within the Spirit-led course of the apostolic mission. The specific authority of the church of Rome derived from her honor as the place to which the Spirit led Peter and Paul, in the book of Acts the Spirit's two primary missionary instruments, for their final work and for their own perfecting in martyrdom; the Spirit was therefore expected to maintain the Roman church as a “touchstone” of fidelity to the apostolic work and faith.

But one need not enter the realm of science fiction* now to imagine a time in which Rome, with its congregation and pastors, no longer existed. Yet the role that initially developed around that church, once developed and theologically validated, would still be necessary. Surely an ecumenical council or other magisterial organ of the one church could and should then choose a universal pastor, elsewhere located. The new ecumenical pastor might of course still be styled “bishop of Rome,” but this is neither here nor there to our problem. Probably we must judge: identification of the universal pastorate with the Roman episcopacy is not strictly irreversible. On the other hand, hard cases make bad law.

Indeed I did remember correctly, though almost too correctly. For where you see the asterisk in the final paragraph, there is a footnote where Jenson writes the following:

In A Canticle for Leibowitz, by Walter M. Miller, it having become nearly certain, after millenia [sic] of repeated nuclear catastrophes and repeated slow rebirths, that this time nuclear warfare will render the earth permanently uninhabitable, three cardinal bishops are sent to the small human colony of Mars.

Face palm! I was right to think of Jenson’s discussion, since Jenson literally tells the reader he’s thinking of Miller’s novel. Well then! I’ve come full circle. Though having just finished the book, I’m at least in a position to note that Jenson was quoting from memory, since he refers to a colony on Mars rather than a planet in the Alpha Centauri system.

Oh well. Read both books, is the moral of this story.

Anti-sacramentalism

[W]hile sacraments have precarious or penultimate status in religion by and large, it is a distinguishing mark of Christianity that it is decidedly and finally sacramental. If God is one thing humans have to communicate with one another, to the saying of which the word’s embodiment is essential, God is the one thing Christians cannot cease to communicate.

[W]hile sacraments have precarious or penultimate status in religion by and large, it is a distinguishing mark of Christianity that it is decidedly and finally sacramental. If God is one thing humans have to communicate with one another, to the saying of which the word’s embodiment is essential, God is the one thing Christians cannot cease to communicate. Insofar as our communities remain faithful to the specific gospel, we are bound to embodied discourse. All anti-sacramentalism in the church is forgetfulness of which God we worship; it is idolatry. The gospel wants to be as visible as possible.

—Robert W. Jenson, Visible Words: The Interpretation and Practice of Christian Sacraments (1978), 31-32

New article published: “The Church and the Spirit in Robert Jenson's Theology of Scripture" in Pro Ecclesia

I have an article in a two-part symposium in Pro Ecclesia commemorating the life and thought of Robert Jenson, and though the issues are not yet published, my article is available in an early, online-first capacity. Here's the abstract:

In the last two decades of Robert Jenson’s career, he turned his attention to the doctrine of Scripture and its theological interpretation. This article explores the dogmatic structure and reasoning that underlie Jenson’s thought on this topic. After summarizing his theology of Scripture as the great drama of the Trinity in saving relation to creation, the article unpacks the doctrinal loci that materially inform Jenson’s account of the Bible and its role in the church. Ecclesiology and pneumatology emerge as the dominant doctrines; these in turn raise questions regarding Jenson’s treatment of the church’s defectability: that is, whether and how, if at all, the church may fail in its teaching and thus in its reading of Scripture.

Check out the whole thing here.

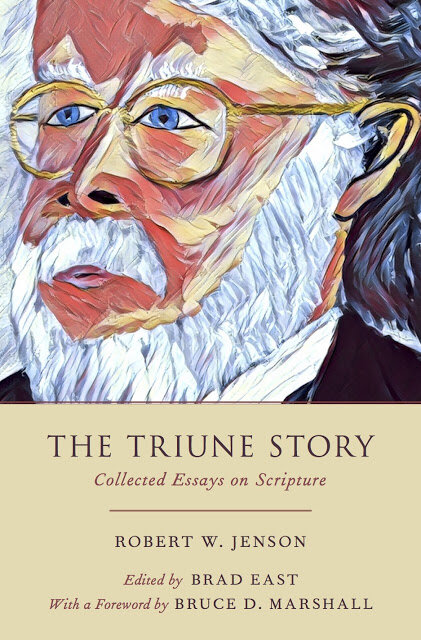

The blurbs are in for The Triune Story

"Robert Jenson was undoubtedly one of the most influential and original English-speaking theologians of the last half century, eloquent, controversial, profoundly in love with the God of Jewish and Christian Scripture. This invaluable collection shows us the depth and quality of his engagement with the text of Scripture: we follow him in his close reading of various passages and his tracing of various themes, and emerge with a renewed appreciation of the scope of his doctrinal vision. He offers a model of committed, prayerful exegesis which is both a joy and a challenge to read." —Rowan Williams

"Robert Jenson never needed to be reminded that the most interesting thing about the Bible is God. For those frustrated by biblical scholars apparently willing to harangue us about anything but God, The Triune Story will come as a healing draught. With vigor, clarity, and learning, Jenson reminds us that the apostolic faith, ancient yet always future, is the only true key to the understanding and interpretation of Scripture." —Christopher Bryan, author of The Resurrection of the Messiah and Listening to the Bible

"The never ending task of helping students learn how to read scripture theologically just got a lot easier with this collection. Jenson had a lot to say about the theological interpretation of scripture—much of it important and worthy of offering to future generations as an able guide into the strange world of the bible. Jenson's work on scripture will also be studied by generations of historians and theologians who will want to see a theologian in full intellectual flight thinking about scripture and society and doing so with a seriousness almost unmatched in the latter half of the twenty century. This is a book both important and necessary." —Willie James Jennings, Associate Professor of Systematic Theology and Africana Studies, Yale Divinity School

"In a cultural and theological milieu in the twentieth century that viewed the Bible as a book from the past, Robert Jenson put the biblical story as a living Word of God at the center of his thought. The essays in this rich collection are as fresh and stimulating today as they were when first published." —Robert Louis Wilken, William R. Kenan, Jr., Professor Emeritus of the History of Christianity, University of Virginia

Pre-order The Triune Story today!

Oxford says the book will be out mid-June; Amazon says mid-July. I'd go with Amazon on that one. I'm working on indexing the book right now, after which point, late this month, I'll get the proofs. So perhaps the revised proofs will be ready by May 1? I don't know how quickly the turnaround is on these kinds of books, but perhaps quicker than I imagined. We also need to get the blurbs, about which more soon.

But, anyway, I only just happened upon this bit of news, and I couldn't be more delighted. This volume is going to be a real resource going forward, for Jenson scholars as well as for theologians interested in Scripture more broadly. I can't wait for y'all to have it in your hands.

And speaking of which, pre-order today! And how could you not, gazing on that gorgeous cover (image by the great Chris Green):

Jenson on being stuck with the Bible's language

—Robert Jenson, "The Hidden and Triune God," in Theology as Revisionary Metaphysics: Essays on God and Creation, 69-77, at 70-71

Happy news: I'm editing a collection of Jenson's writings on Scripture

My thanks to Cynthia Read and to the editorial team at Oxford for supporting this book. Before his passing earlier this fall, Jens gave the project his blessing, and I hope it is a testament to the beauty and abiding value of his work both for the church and for the theological academy.

My hope is to have the book published by the end of next year, though that obviously depends on many forces outside my control. Perhaps even in time for a session at AAR/SBL...?

In any case, this has been an idea in the back of my mind for a few years now, and it's a joy to see it become a (proleptic) reality. Now y'all just be sure to buy it when it comes out.

Jenson's passing: tributes, links, and resources

(If you have a link for me to add, mention it in the comments, on Twitter @eastbrad, or by email: bxe03a AT acu DOT edu.)

Remembering Jenson:

Victor Lee Austin: "Can These Bones Live? A Sermon Preached at Jenson's Funeral"

Carl E. Braaten: "Encomium for an Evangelical Catholic: Robert Jenson (1930–2017)"

Christian Century: "Robert Jenson, theologian revered by many of his peers, dies at age 87"

Christianity Today: "Died: Robert Jenson, 'America's Theologian'"

Brad East: "Rest in peace: Robert W. Jenson (1930–2017)"

Kim Fabricius: "Clerihew for Robert W. Jenson (1930–2017)"

Paul R. Hinlicky: "Robert Jenson and the God of the Gospel"

Scott Jones: "Can These Bones Live?"

Alvin F. Kimel, Jr.: "Reminiscences and Memories"

Peter Leithart: "Remembering Jenson"

Mars Hill Audio: "In Memoriam: Robert W. Jenson (1930–2017)"

Elizabeth Palmer: "Robert Jenson and the Search for the Divine Feminine"

R. R. Reno: "Robert W. Jenson, R.I.P."

Fred Sanders: "3 Favorite Robert Jenson Moments"

Secondary Resources:

Brad East: "What is the Doctrine of the Trinity For? Practicality and Projection in Robert Jenson's Theology"

Colin E. Gunton, ed.: Trinity, Time, and Church: A Response to the Theology of Robert W. Jenson

David Bentley Hart: "The Lively God of Robert Jenson"

Ben Myers: "Robert W. Jenson and Solveig Lucia Gold: Conversations with Poppi about God"

Wolfhart Pannenberg: "Systematic Theology: Volumes I & II"

Fred Sanders: "Unintended Consequences of Shoving (Robert W. Jenson)"

Brian K. Sholl: "On Robert Jenson's Trinitarian Thought"

Scott R. Swain: The God of the Gospel: Robert Jenson's Trinitarian Theology

Stephen John Wright: Dogmatic Aesthetics: A Theology of Beauty in Dialogue With Robert W. Jenson

Stephen John Wright and Chris E. W. Green, ed.: The Promise of Robert W. Jenson's Theology: Constructive Engagements

Primary Resources:

"Don't Thank Me, Thank the Holy Spirit" (Crackers and Grape Juice Podcast, 2017)

A Theology in Outline: Can These Bones Live? (ed. Adam Eitel; OUP, 2016)

"Ecumenism's Strange Future" (Living Church, 2014)

"On 'the Philosophy that Attends to Scripture'" (Syndicate, 2014)

"It's the Culture" (First Things, 2014)

"Reversals: How My Mind Has Changed" (The Christian Century, 2010)

"The Burns Lectures on 'The Regula Fidei and Scripture'" (University of Otago, New Zealand, 2009)

"A Theological Autobiography, to Date" (dialog, 2007)

"God's Time, Our Time: An Interview with Robert W. Jenson" (The Christian Century, 2006)

"Reading the Body" (The New Atlantis, 2005)

Song of Songs (Interpretation; WJKP, 2005)

"Can We Have a Story?" (First Things, 2000)

Systematic Theology: Volume I: The Triune God (OUP, 1997)

"How the World Lost Its Story" (First Things, 1993)

Christian Dogmatics (with Carl E. Braaten; Fortress, 1984)

Story and Promise: A Brief Theology of the Gospel About Jesus (Fortress, 1973)

Rest in peace: Robert W. Jenson (1930–2017)

I first read Robert Jenson in the summer of 2009, following the first year of my Master of Divinity studies at Emory University, on a sort of whim. I had been introduced to him through an essay by Stanley Hauerwas, originally published in a festschrift for Jenson but republished in the 2004 collection of Hauerwas's essays called A Better Hope. Oddly, I had the impression that Hauerwas didn't like Jenson, but at a second glance, I realized his great admiration for him, so I not only read through Jenson's whole two-volume systematics that summer, but I blogged through it, too—in extensive detail. In fact, it was the first systematic theology I ever read.

Eight years later, and I am a systematic theologian. Fancy that.

Jenson passed away yesterday, having been born 87 years earlier, one year after the great stock market crash of 1929. He lived through the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, Roe v. Wade, the rise and fall of the Religious Right, the fall of the Soviet Union, September 11, 2001, the election of the first African-American U.S. President, and much more. He also lived through, and in many ways embodied, a startling number of international, ecclesial, and academic theological trends: ecumenism; doctrinal criticism; analytic philosophy of language; Heidegerrian anti-metaphysics; French Deconstructionism; the initially negative then positive reception of Barth in the English-speaking world; the shift away from systematics to theological methodology (and back again!); post–Vatican II ecclesiology; "death of God" theology; process theology; liberation theologies (black, feminist, and Latin American); virtue ethics; theological interpretation of Scripture; and much more.

Jenson studied under Peter Brunner in Heidelberg and eventually spent time in Basel with Barth, on whose theology he wrote his dissertation, which generated two books in his early career. He was impossibly prolific, publishing hundreds of essays and articles as well as more than 25 books over more than 55 years.

Initially an activist, Jenson and his wife Blanche—to whom he was married for more than 60 years, and whom he credited as co-author of all his books, indeed, "genetrici theologiae meae omniae"—marched and protested and spoke in the 1960s against the Vietnam War and for civil rights for African-Americans. His politics was forever altered, however, in 1973 with Roe v. Wade. As he wrote later, he assumed that those who had marched alongside him and his fellow Christians would draw a logical connection from protection of the vulnerable in Vietnam and the oppressed in America to the defenseless in the womb; but that was not to be. Ever after, his politics was divided, and without representation in American governance: as he said in a recent interview, he found he could vote for neither Republicans nor Democrats, for one worshiped an idol called "the free market" and the other worshiped an idol called "autonomous choice," and both idols were inimical to a Christian vision of the common good.

In 1997 and 1999, ostensibly as the crown and conclusion to 70 years' work in the theological academy, Jenson published his two-volume Systematic Theology, arguably the most read, renowned, and perhaps even controversial systematic proposal in the last three decades. There his lifelong interests came together in concise, readable, propulsive form: the triune God, the incarnate Jesus, the theological tradition, the nihilism of modernity, the hope of the gospel, and the work of the Spirit in the unitary church of the creeds. Even if you find yourself disagreeing with every word of it, it is worth your time. As my brother once told me, he wasn't sure what he thought about the book when he finished the last page, but more important, he felt compelled to get on his knees and worship the Trinity. Surely that is the final goal of every theological system; surely nothing could make Jenson more pleased.

Happily, those of us who loved and benefited from Jenson's work were blessed with nearly two more decades of output from his mind and pen following the systematics. Some of this work was his most playful and provocative; it also included two biblical commentaries, on the Song of Songs and Ezekiel. There are treasures not to be overlooked in those lovely works.

If Hauerwas was my gateway to theology as a world, Jenson was my guide, my Virgil. I didn't know the names of Irenaeus and Origin and Cyril and Nyssa and Damascene and Radbertus and Anselm and Bonaventure before him; or at least, I had no idea what they had to say. And I certainly hadn't considered putting Luther and Edwards and Schleiermacher and Barth together in the way he did. Perhaps most of all, I didn't know what systematic theology could be, the intellectual heights that it could reach and that it necessarily demanded, or the way in which it could be conducted as an exercise in spiritual, moral, and mental delight: bold, wry, unflinching, assertive, open-handed, open-ended, argumentative, humble, urgent, sober, at peace. Jenson knew more than most that theology is simultaneously the most and the least serious of tasks. It is of the utmost importance because what it concerns is the deepest and most central of all realities: God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the creator, sustainer, and savior of all. But self-seriousness is a mistake precisely because of that all-encompassing subject matter: God is in charge, and we are not; God, not we, will keep the gates of hell from prevailing against the church; God alone will steward the truth of the gospel, which we do indeed have, but only as we have been given it, and which we understand only through a glass darkly. Jenson knew, in other words, that in his theology he got some things, even some big things, wrong. And he could rest easy, like his teacher Barth, because God's grace reaches even to theologians. Although it is true that the church's teachers will be judged more harshly than others, the judgment of God is grace, and it goes all the way down.

God's grace has now been consummated in this one individual, God's servant and theologian Robert. He is at rest with the saints in the infinite life of God—the God he called, with a wink in his eye, both "roomy" and "chatty." May his rest be as full of talk as his life was on this earth, as eloquent and various as the eternal conversation of Jesus with his Father in their Spirit. And, God be praised, may he be raised to new and imperishable life on the last day, as he so faithfully desired and bore witness to in his work in this world. May that work give glory to God, and may it remind the church militant of the God of the gospel and the life we have been promised in Jesus, the life we can taste even now, the life of the world to come.

I've got a new article out in Modern Theology

"This articles engages the theology of Robert Jenson with three questions in mind: What is the doctrine of the Trinity for? Is it a practical doctrine? If so, how, and with what implications? It seeks, on the one hand, to identify whether Jenson’s trinitarian theology ought to count as a “social” doctrine of the Trinity, and to what extent he puts it to work for human socio-practical purposes. On the other hand, in light of Jenson’s career-long worries about Feuerbach and projection onto a God behind or above the triune God revealed in the economy, the article interrogates his thought with a view to recent critiques of social trinitarianism. The irony is that, in constructing his account of the Trinity as both wholly determined in and by the economy and maximally relevant for practical human needs and interests, precisely in order to avoid the errors of Feuerbachian “religion,” Jenson ends up engaging in a full-scale project of projection. Observation of the human is retrojected into the immanent life of the Trinity as the prior condition of the possibility for the human; upon this “discovery,” this or that feature of God’s being is proposed as a resolution to a human problem, bearing ostensibly profound socio-practical import. The article is intended, first, as a contribution to the work, only now beginning, of critically receiving Jenson’s theology; and, second, as an extension of general critiques of practical uses of trinitarian doctrine, such as Karen Kilby’s or Kathryn Tanner’s, by way of close engagement with a specific theologian."

The article has its origins in a term paper I wrote for Linn Tonstad at Yale, in a seminar a few years ago in which we read the manuscript for what eventually became God and Difference, a book now receiving warranted attention from all over the place, most recently in a series of rousing responses in Syndicate. It also has a degree of overlap with Ben Myers's recent series of tweets on the Trinity (gathered together in a post) summarizing the classical approach to the doctrine over against the last century's innovations and trends. Consider my article an exercise in that sort of frumpy theology—borrowing my friend Jamie Dunn's coinage—but in this case focused on a single important figure on the contemporary scene. I love Jenson's work and it means a great deal to me, but the article identifies within his trinitarian project a problem (a significant one, I think) internal the logic of his own system. I look forward to hearing what others think, especially those who read and value Jenson's thought.

The liturgical/praying animal in Paradise Lost

There wanted yet the master-work, the end

Of all yet done—a creature who, not prone

And brute as other creatures, but endued

With sanctity of reason, might erect

His stature, and upright with front serene

Govern the rest, self-knowing, and from thence

Magnanimous to correspond with Heaven,

But grateful to acknowledge whence his good

Descends; thither with heart, and voice, and eyes

Directed in devotion, to adore

And worship God Supreme, who made him chief

Of all his works.

What is striking about this account is the way in which the rationality ascribed to humanity, unique among all creatures, is specified and given content. Initially it seems quite in line with classical accounts: humans are distinct by virtue of their reason. But what sort of reason, and to what end?

According to Milton, men and women are rational inasmuch as, and so that, they "correspond with Heaven," thanking God for his manifold gifts and worshiping him as the source of all, including their own, being and goodness. Which is to say, human rationality is at once the condition and the means of prayer, which is reason's telos. What sets apart human beings from other animals is that they use words to talk to and about God in thanks and praise. As Robert Jenson has it, human beings are "praying animals." Or in Jamie Smith's words, homo sapiens is homo liturgicus.

Rationality, for Milton, as for Jenson and Smith, isn't the cold logic of unbiased inquiry or instrumental reason. It is the devotion of a heart on fire for the Creator, manifested in the speech of adoration and love, awe and thanksgiving. Rationality is correspondence with heaven.